Why does accountability matter for Uniswap?

Over the past year, developments in Uniswap governance vividly illustrate accountability challenges in two key areas of crypto: licensure and partnerships. With the growth of DAOs and DAO-to-DAO relations, the topic of partnership accountability has become increasingly relevant. D2D frameworks provide tools to build economies within DAOs characterized by fluid relationships within and across organizations, unlike their brick-and-mortar counterparts. For instance, we are beginning to see DAO mergers, such as the Rari and Fei one, and D2D joint ventures that promise to facilitate partnerships between DAOs.

Additionally, relations within DAOs have grown in complexity. The rise of service DAOs has proven the demand for cryptonative organizations that offer services such as consulting, development, and treasury management. Furthermore, as protocols advance on the path of progressive decentralization, giving control to their communities through governance tokens, we see core teams dispersing into subDAOs, like in the case of MakerDAO’s Core Units (autonomous working groups voted and funded by governance). We are also witnessing DAOs establishing novel “Business-to-DAO” relationships with former core teams, such as the case of Aave and Bored Ghost Developing Labs, in which the new development company (composed of the former core team) is now working for the DAO after proposing its services via governance.

As attempts are made to expand the Uniswap protocol across multiple chains and L2s, the Uniswap governance forum provides us with multiple interesting case studies of partnership negotiation.

In particular, the introduction of a Business Source License 1.1 (BSL) for v3 offers new opportunities and challenges for accountability in partnerships.

The BSL was introduced by Uniswap Labs to limit the use of the v3 source code in a commercial setting for up to two years, at which point it will convert to a GPL license in perpetuity, in order to protect the protocol from forking for the first two years of its existence. With the launch of the UNI token, the management of the license has been transferred to governance. Projects that want to use the code of v3 or part of it in production need to request an Additional Use Grant to the community. In this sense, the licensing process is also an example of partnership accountability and license enforcement crossing over.

The BSL addresses the tension between the ideological emphasis on open-sourcing vs the threat of forking and its impact on the sustainability of crypto as an innovation ecosystem. It emerges as a compromise between these two needs, seeking to not entirely prevent but to at least delay forking. At present it is used by Uniswap as well as Aave, and it’s been received with both negative criticism and praise by the wider DeFi community.

If business source licenses are to become more widely used to counterbalance the tendency towards forking, Uniswap is a useful case study to investigate more closely the strengths, weaknesses and possible improvements of the application of BSLs as a mechanism to facilitate partnerships and accountability across protocol actors.

Defining accountability in DeFi

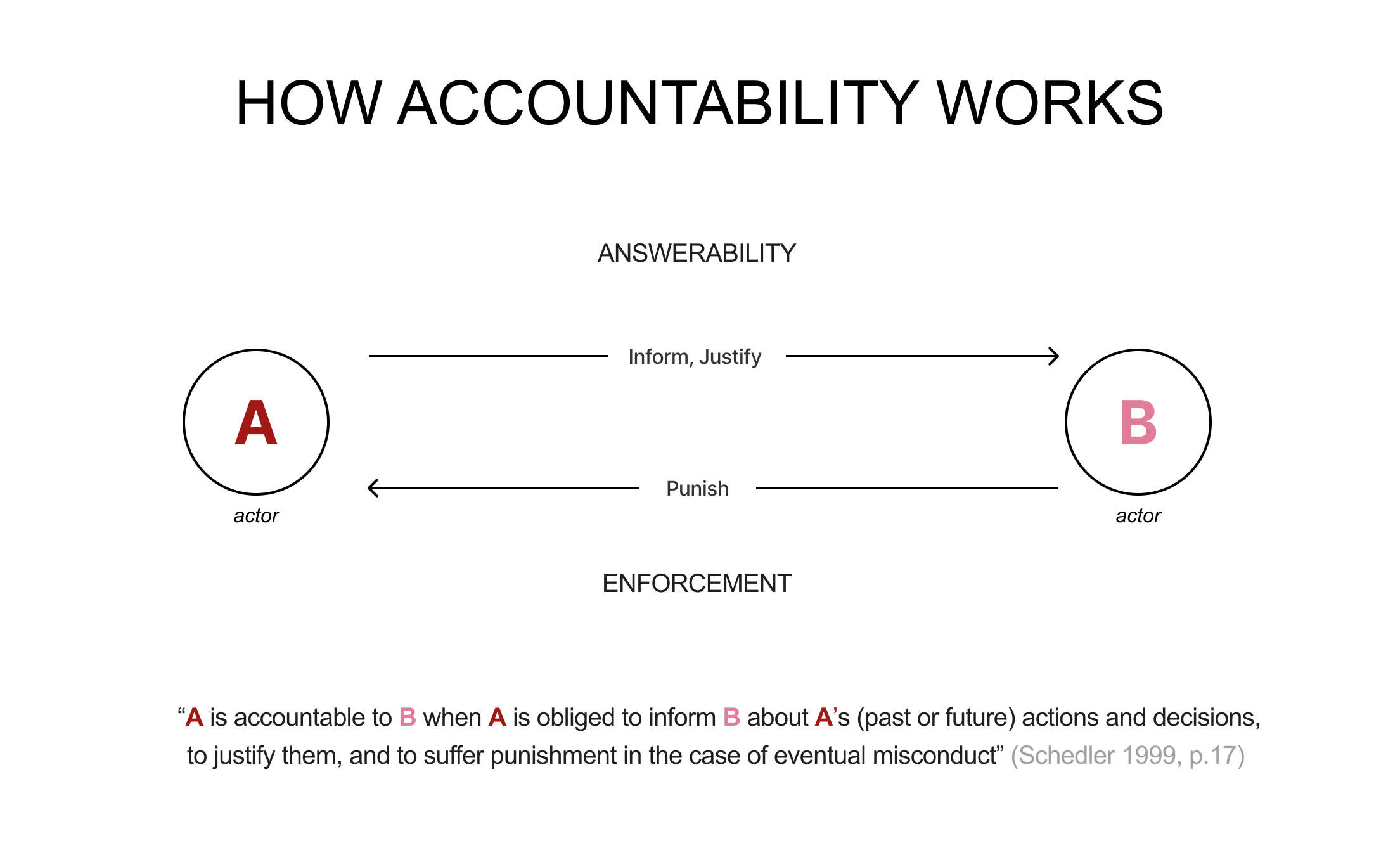

While accountability can be construed normatively “as a set of standards for the evaluation of the behavior of public actors” or even as a positive virtue itself, we focus on the more descriptive sense of accountability as a mechanism or “arrangement in which an actor can be held to account” (Bovens 2010, p.946). But what exactly does it mean to hold an actor to account? Following Schedler’s one-sentence definition: “A is accountable to B when A is obliged to inform B about A’s (past or future) actions and decisions, to justify them, and to suffer punishment in the case of eventual misconduct” (Schedler 1999, p.17). Schedler sums up monitoring and justification under the banner of ‘answerability’, that is, mechanisms to constrain behavior towards higher ex-ante accountability. Conversely, he uses the term punishment synonymously with ‘enforcement’ (ibid., p.14) – these are mechanisms used to sanction breaches of accountability. They provide “different ways of preventing and redressing the abuse of political power…[by] subjecting power to the threat of sanctions; obliging it to be exercised in transparent ways; and forcing it to justify its acts” (ibid.).

Advocates of crypto have also been concerned with preventing abuses of power. But rather than waiting to see if someone abuses their power and reacting with demands for information or enacting punishment, blockchain applications may be designed to eliminate or significantly constrain the possibility to abuse power before it ever happens:

“Trustlessness is the ability of the application to continue operating in an expected way without needing to rely on a specific actor to behave in a specific way even when their interests might change and push them to act in some different unexpected way in the future.” (Buterin 2020).

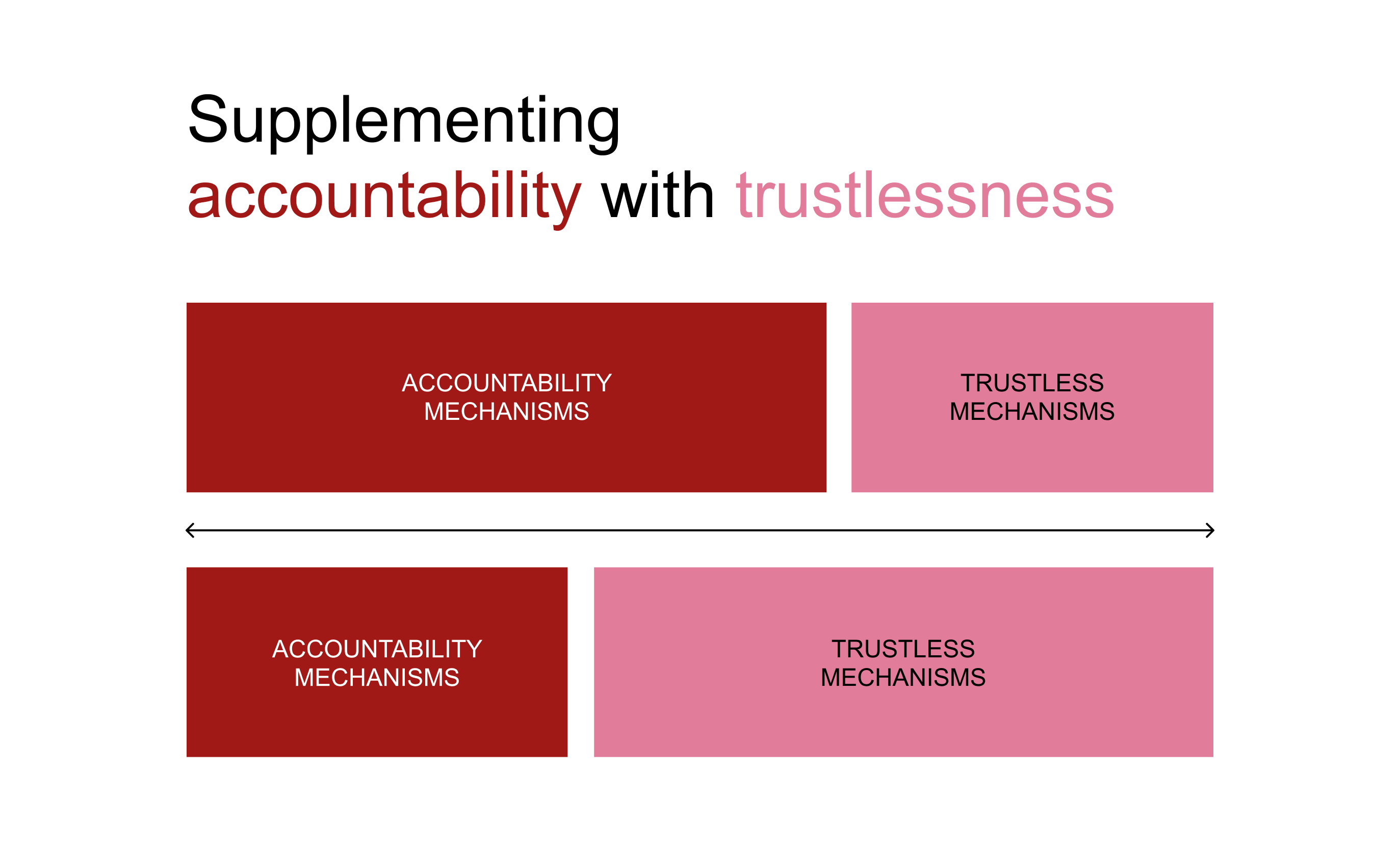

Importantly, as Buterin notes, no blockchain application can be fully trustless (given that they are always built by humans). Instead, trustlessness exists on a spectrum where “some applications are much closer to being trustless than others” (ibid.). Conceptualizing trustlessness as a spectrum allows us to understand the mutually supportive relationship between accountability mechanisms of answerability and enforcement, and crypto-native, self-executing mechanisms: lower levels of trustlessness can be supported by higher levels of accountability; for situations where answerability and/or enforcement cannot be guaranteed, limited accountability mechanisms can be supported by more trustless designs.

If full trustlessness is impossible, and accountability mechanisms will always be needed, it is vital that the crypto space develops a deeper understanding of the strengths of accountability mechanisms and how to appropriately apply them. In our enthusiasm for the potential of trust minimization, it is easy to overlook the fact that accountability mechanisms of answerability and enforcement can be both robust, but also flexible and adaptive in ways that hard-coded trust minimization mechanisms cannot be. At the same time, the problem space of on-chain mechanism design to reduce the burden on traditional accountability mechanisms is ripe for innovation, especially at Uniswap.

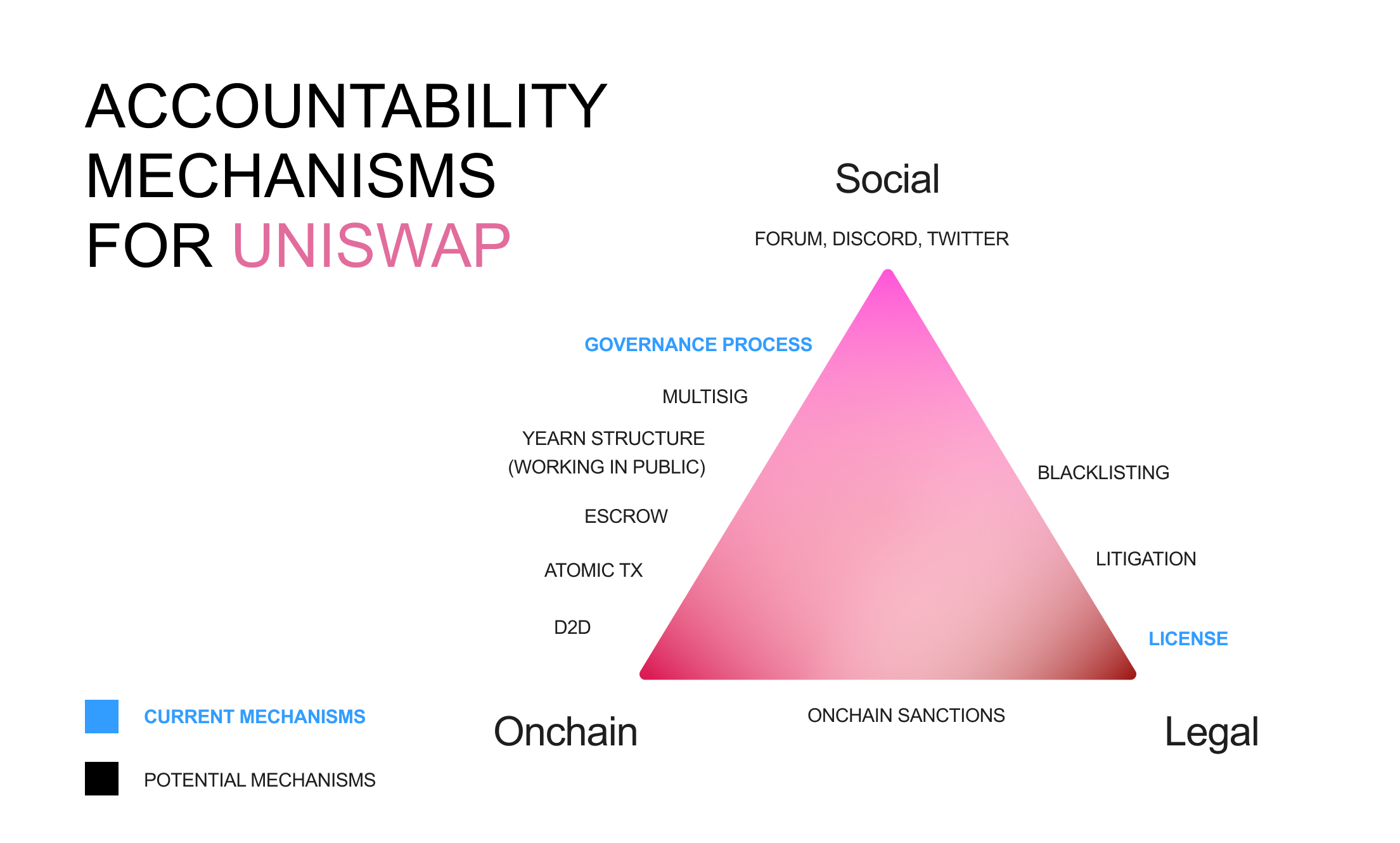

Our research explores three types of mechanisms that protect against conduct breaches within partnerships and licensure relationships: crypto-native mechanisms, legal mechanisms and social mechanisms. Importantly, these mechanisms can and should exist in combination with one another to reinforce the overall accountability in partnerships and licensing agreements. Through an analysis of three case studies of partnership and licensure negotiations in Uniswap governance, we will illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of mechanisms currently in place, before suggesting additional ones that could be developed and implemented.

Our findings can be summarized as follows:

In the absence of strong on-chain mechanisms, Uniswap primarily relies on legal mechanisms for the enforcement dimension of accountability for licensing and partnerships. These enforcement mechanisms could be made more robust through stricter requirements for A) legal personhood for both the Uniswap DAO and teams proposing partnerships and requesting Additional Use Grants and B) clarity of promises made as part of partnerships and license requests, thereby improving their legal enforceability.

Uniswap relies on social mechanisms for the answerability dimension of accountability for licensing and partnerships; namely, through the implicit and explicit rules that govern behavior on the governance forum, and the monitoring, criticism and calls for justification of the behavior of Uniswap partners and license recipients in the public forum of Twitter. These answerability mechanisms could be made more effective through more active, systematic approaches to A) informal relationship management with licensees and partners and B) requiring greater transparency from licensees and partners in their public communications.

Finally, currently Uniswap does not make use of on-chain trust-minimizing mechanisms, nor hybrid on-chain/off-chain mechanisms to support the performance of licensure and partnerships. Rather than simply trusting (or hoping) that partners and licensees would deliver on what they promised as part of their governance proposals, new mechanisms could be introduced to reduce the burden on legal enforcement and social answerability as primary accountability mechanisms. These are: A) on-chain mechanisms that leverage escrows, atomic escrows and SAFT contracts to make the execution of a proposal conditional on the delivery of funds and B) hybrid mechanisms aimed to increase process transparency, such as depositing funds to a community-managed multisig prior to the proposal’s execution.

Case studies

Below we revisit three recent cases of partnerships and licensing requests in the Uniswap forum in order to evaluate the current state of Uniswap’s accountability and illustrate what mechanisms and processes—legal, on-chain and social constraints and sanctions—could improve it.

Case study 1: Uniswap and Polygon

In November 2021, L2 protocol Polygon submitted a governance proposal to authorize the deployment of Uniswap to its proof-of-stake chain, sparking activity in the forum and renewed interest in scaling solutions. The proposal didn’t request an Additional Use Grant. It was effectively the first case of partnership between Uniswap’s community and a large protocol. Unlike Arbitrum and Optimism, which benefited from the support and guidance from Uniswap Labs, Polygon interacted directly with governance.

The proposal, which passed the onchain vote in December 2021 with 72 million UNI in favor, included both financial and non-financial incentives in the form of a liquidity mining program and cross-promotion initiatives, respectively. As it stated, their proposal included:

- Financial incentives: “up to $20M”, divided as follows

- Up to $15M for a long-term liquidity mining campaign;

- Up to $5M towards the overall adoption of Uniswap on Polygon.

- Technical incentives: actively participating in the design and execution of liquidity mining campaigns;

- Co-branding and cross-promotion: promoting Uniswap V3 as “money lego” with projects in the Polygon Defi ecosystem, at hackathons and other developer-focused events and efforts.

However, by March 2022 the liquidity mining program hadn’t been delivered yet. This led some Uniswap community members to raise their concerns through Crypto Twitter, to which Polygon’s CEO Mihailo Bjelic replied by reassuring the community and pointing to the time-consuming nature of having to design and deploy the campaign themselves.

Two weeks later Polygon announced the first phase of its liquidity mining program by deploying $3M in incentives using Arrakis Finance, a third-party protocol for tokenized LP vaults. A month later, in mid May, Polygon announced yet again another change to its program, generalizing the liquidity mining program for Uniswap to be 100% KPI-based (in partnership with UMA protocol) so that the highest performing managers would get all the rewards.

None of these strategies was discussed with the Uniswap community, neither during the proposal phase nor afterwards.

It's been 100 days since proposal to deploy @Uniswap v3 to @0xPolygon PoS passed.

— BOR4 (@B0R444) March 31, 2022

A quick 🧵on pending commitments from Polygon team that nobody talks about.

TL;DR; Uniswap is still waiting for 15M LM campaign that was promised in the proposal

Existing elements of accountability

In order to assess what better accountability mechanisms Uniswap could implement in order to hold partners accountable, let’s first look at the current ones.

At the time of the proposal, there were no legal constraints or enforcement mechanisms in place. Polygon did not officially request an Additional Use Grant that could have introduced a level of legal accountability. At the same, the DAO itself lacks legal personhood that would have enabled it to legally enforce the terms of the proposal if deemed necessary.

The implicit norms of the governance process, as well as its explicit requirement to submit a proposal and obtain approval over a three-staged vote, provide a minimum of social constraints. Here the information contained in the proposal itself offers ways to increase the answerability of the proposer toward Uniswap.

From looking closer at the wording of the proposals, it is possible to interpret that Polygon was willing to commit up to $20M total between “long-term liquidity mining campaign” and “adoption of Uniswap on Polygon” – so any number between $0 and $20M. Depending on interpretation, they have fulfilled their part on the agreement with Uniswap DAO.

They also promised to “actively participate in the design and execution of liquidity mining campaigns”, which is not well-defined. What does active participation mean in this context, and how does Uniswap DAO keep Polygon accountable on the promised financial incentives? Since the vote went through without clarifications on those missing details, disagreements emerged at a later stage.

It’s also unclear whether Polygon fulfilled the points in the proposal pertaining to cross-promotion since there is no documentation available.

How do tokenholders and DAO members follow along the progress to keep the DAOs accountable? Reconstructing a linear timeline of events is time consuming and not easily feasible since the information is scattered between on-chain proposals, twitter threads, different forums and blog posts. Accountability becomes especially harder if information is not easily accessible.

For example, Polygon started the liquidity mining program during April, but the thread on Uniswap’s forum does not link or mention it. The last post, from March 31, is an inquiry into the delays of the liquidity mining program.

The enforcement mechanisms in place at the time of the proposal were limited to the implicit prospect of social and reputational gains and damages. As the largest DEX, Uniswap benefits from a strong brand and reputation, which would deter dishonest behavior. However, this hasn’t prevented the delay on Polygon’s side and the undiscussed changes to its liquidity mining program.

Case study 2: Uniswap and Voltz

In December 2021, Voltz – a yet-to-be-launched automated market maker for interest rate swaps – requested an Additional Use Grant through Uniswap governance. The Voltz protocol relies, in part, upon the use of concentrated liquidity in the Uniswap v3 code base. This was the first licensing request to Uniswap governance, kickstarting an inflow of proposals by other projects in the forum and setting a precedent for DAO2DAO collaborations in Uniswap.

In exchange for an Additional Use Grant under the Business Source License, the temperature check included the following incentives:

- Financial incentives in the form of future tokens: the proposal stated that Voltz “would like to offer the Uniswap Treasury 1% of Voltz’s future token supply”, effectively proposing a metagovernance relation between Uniswap DAO and the Voltz DAO;

- Non-financial incentives: ecosystemic benefits such as reinforcing Uniswap’s role as leading protocol in DeFi.

The proposal successfully passed all three phases of the governance process, with the final vote occurring in March 2022. The effect of the on-chain vote was to set a text record at v3-core-license-grants.uniswap.eth including the license language.

Existing elements of accountability

Beyond the implicit norms of the governance process with its 3 phases, and the text of the Business Source License itself, there are no other elements of accountability.

Although the proposal was executed on-chain, there are no crypto-native remedies available to Uniswap if a breach of the license were to occur, since the license is essentially a “paper” agreement memorialized on-chain. For Uniswap to be able to legally enforce the terms of the license, several elements need to be present, which we describe below.

Having a standing to sue

Filing a lawsuit generally requires a party or parties with “standing,” i.e., sufficient skin in the game. Given the “alegality by design” (De Filippi, Mannan, and Reijers 2021) that characterizes blockchain protocols, the DAO itself lacks legal personhood and needs to rely on an external entity that acts in the interest of the protocol. In this case, the entity with standing to sue is Uniswap Labs, the licensor of V3 BSL. This is not to say that only registered legal entities may file suit, but the question is who would have standing to file suit on behalf of the DAO. As the protocol is on its path of progressive decentralization it would be beneficial for governance to rely on an entity that has its best interests at the core of its mission and the resources necessary to enforce accountability. With the recent approval of the creation of the Uniswap Foundation – effectively the first case of a foundation emerging out of a DAO treasury – Uniswap will soon have the support of a legal entity with the authority to enforce accountability to the benefit of the protocol and its ecosystem.

Beyond having a standing to sue, there are two other key factors that determine the capacity of Uniswap to legally enforce the license: the clarity of the promise at the moment of the governance proposal, and the authority of the promise maker.

Clarity of promise

First, it is worth considering whether Voltz’s promise of future tokens is sufficiently clear to be enforceable in the first place. “1% of Voltz’s future token supply” is not a model of clarity, given that it fails to address terms viewed as essential by the industry, like vesting and dilution (i.e., what happens if token supply is subject to inflation). In some jurisdictions, a promise that is too vague may be viewed as an unenforceable “agreement to agree.”

That said, principles of equity would militate toward this promise being enforced, given that Uniswap relied upon the promise by granting the license, and Voltz undoubtedly benefited from the license. Courts routinely interpret and enforce contracts much vaguer than this. A court would likely construe the promise against Voltz (the promise maker) and in favor of Uniswap. A court would also likely reference industry standards and the course of conduct between the parties in filling any gaps. For example, if Voltz founders are not subject to vesting, then Uniswap probably should not be, either.

Authority of Promise Maker

Second, it is worth considering whether the promise maker had authority to offer 1% of Voltz’s future tokens. The proposer was an individual under the pseudonym ‘simonj.’ From the proposal alone, it isn’t possible to reliably confirm whether ‘simonj’ represents Voltz. However, there is also an announcement in the Voltz Discord posted by an ’0xSimon’ (presumably the same individual) linking to the proposal, and Twitter posts from the Voltz Labs account and ’0xSimonJones’ referring to the proposal.

But that is not necessarily the end of the inquiry. It would also need to be ascertained whether a company like Voltz has governance procedures that must be followed to authorize substantial transactions. For instance, Voltz’s governance documents might require approval by a board of directors to approve a grant of tokens. In such a case, if the board had not provided the required approval, then Uniswap may have difficulty specifically enforcing the promise.

Remedy

If a court were to find Voltz in breach of the license, it may potentially order (1) payment of money damages and/or (2) ceasing use of the Uniswap codebase. However, the second remedy would only be meaningful if Voltz has procedures built into its smart contract protocol allowing for a shutdown. This is unlikely, given that the purpose of the license is to authorize certain forking activity (not activity with the main protocol deployment itself).

Case study 3: Uniswap and Moonbeam

More recently, in late March 2022, cross-chain provider Nomad and Blockchain at Berkley requested an Additional Use Grant to deploy Uniswap V3 on Moonbeam. Moonbeam is an EVM-compatible Polkadot parachain, aiming to serve as a port-of-entry for Ethereum-native apps to participate in the greater Polkadot ecosystem.

Nomad, in partnership with interoperability protocol Connext, have already created a token bridge between Moonbeam and Ethereum and have begun to drive cross-chain liquidity from Ethereum into Moonbeam. With Uniswap V3 deployed on Moonbeam the projects would benefit hugely from the proposal passing.

After successfully passing the Temperature Check and Consensus Check with not much forum discussion, in May 2022, the onchain Governance Proposal was posted with new details and information regarding the financial and non-financial incentives provided.

- Financial incentives in the form of a grant to UGP: Nomad and Moonbeam Foundation committed to grant 2.5mm USD to UGP for the development of multichain research and solutions for the Uniswap community. However, the denomination of the funds remain unclear (it is assumed it will be in USD however this hasn’t been clarified).

- Technical incentives: By approving this proposal, Uniswap protocol is able to benefit from Nomad’s bridging solution that enables the relay of governance decisions from Ethereum Uniswap to the other deployments.

- Co-branding: Uniswap’s brand expansion into the Polkadot ecosystem.

The proposal passed with over 50M favorable votes on May 19, and it is the first one that sees Uniswap deploying on a chain that is not part of the greater Ethereum ecosystem.

Existing elements of accountability

The primary accountability mechanism that was available at the time of the proposal is the Business Source License. As mentioned, however, granting a license corresponds to memorializing a paper agreement on-chain. This skeuomorphism between the traditional legal system and the world of smart contracts is perhaps the major accountability gap that Uniswap currently suffers from.

This was made evident in the finalization of the process for both Moonbeam and Gnosis proposals. Due to an error in the text record to be added to the ENS domain at uniswap.eth, both proposals had to be redeployed, which illustrates the lack of effectiveness of this way of registering Additional Use Grants.

On the other hand, the practice of enacting the license change by modifying the text record in the Uniswap ENS is a ritual that grantees need to go through to gain the legitimacy of the community. In this sense, the governance process contributes to strengthening the social accountability of the projects even though it lacks the ability to enforce the terms a posteriori.

looks like both uniswap proposals need to be cancelled due to incorrect text records pic.twitter.com/R9kuXsuB7E

— monetsupply.eth @ MCON (@MonetSupply) May 10, 2022

The final proposal submitted for onchain vote contained new information about the terms of the agreement and the incentives proposed. While no formal on-chain accountability method was present beyond the memorialization of the license in Uniswap ENS subdomain, and there is currently no way for either parties to have legal recourse and enforcement measures, the additional information introduces elements that may reinforce the answerability of the team toward Uniswap, even when these additional elements have not been delivered yet. These are:

- Timeline of deployment: 3-4 weeks between vote and deployment.

- Delivery of funds: “the Moonbeam Foundation commits to allocating the agreed amount of funding to teams referred by UGP to the Moonbeam Foundation. The delivery of the grant funds from the Moonbeam Foundation shall be subject to delivery conditions including the grant recipient’s agreement to the Foundation’s terms and AML and KYC procedures.”

- Technical details: Gnomad module developed in partnership with Gnosis Zodiac “that enables cross-chain governance of Uniswap deployments on chains other than Ethereum mainnet.”

- Auditing details: “conducted by Quantstamp, and expected to complete by early May. We will wait for this re-audit to be finished before we deploy on-chain.”

Additionally, the web of reputational relations within which Nomad/Moonbeam are enmeshed increases the social accountability of the projects:

- While Moonbeam may not be familiar to the Uniswap community, Nomad’s previous research in cross-chain governance in collaboration with Uniswap Labs demonstrates its deep understanding of the Uniswap ecosystem.

- The proposal was created in collaboration with Blockchain at Berkley, a delegate that’s been active in the forum.

- The partnership with Gnosis Chain, which created another licensing proposal around the same time, further signals their commitment.

Ideal elements of accountability: Case study findings

As we’ve seen, the primary accountability mechanism available to Uniswap with regards to partnerships and licensing agreement is the Business Source License. However, this approach relies solely on legal accountability, which comes with significant challenges and expenses, and has limited application against “unlawful” forks. While a judgment in court is possible, that wouldn’t prevent another protocol from using Uniswap’s code even if the terms of the license were not met.

As the Polygon team observed in its on-chain proposal, the proposal itself “has no on-chain functionality other than polling all Uniswap holders.” Without a clear proposal and codified constraints and incentives to orient behavior, holding a partner accountable becomes a challenge.

What mechanisms could strengthen partners' accountability and overcome some of the issues that Uniswap has faced in the cases we’ve explored?

Improving legal enforceability

Vagueness in a proposal isn’t unsolvable, but the clearer the promise, the easier it will be to enforce expeditiously in a court of law. To this end, having an explicit template for partnership requests, which Labs provided for cross-chain licensing at the time of the Moonbeam proposal, can facilitate answerability of the parties.

For legal enforceability, it is critical that the promisor have organizational authority. Uniswap would be well-served to adopt standards for verifying the authority of a proposer prior to relying on a proposal for a license use grant. This is particularly challenging in a context where pseudonymous identities and non-human interests (such as those of ‘the DAO’) are the norm. In both Polygon and Voltz, the proposer was the CEO of the project. In the case of Moonbeam, where the proposal was initiated by a team in the Moonbeam ecosystem in partnership with a blockchain university club, the authority of the proposer is less clear. However, having “proposal sponsors” such as reputable delegates and public figures in Uniswap governance may improve the legal enforceability of a proposal.

For future use grants, Uniswap also might consider adding ‘teeth’ to the license by adding crypto-native remedies. For instance, licensees could be required to post collateral in an escrow smart contract. Of course, this requires the protocol to have sufficient capital on the front end (see below). This may be unworkable for some organizations. However, in the cases discussed – funded startups – this likely could have been budgeted.

Social sanctions

While Uniswap could consider enforcement in a court of law, it could also hold a partner accountable in the court of public opinion. All the cases discussed (Polygon, Voltz, Moonbeam) are legitimate organizations that need to maintain goodwill in the crypto community in order to retain users and obtain new ones. Additionally, there are other stakeholders - such as angel investors - who have an interest in the reputational capital of the projects interacting with Uniswap. The mere threat of, say, a Twitter campaign over a breached license may be enough to prevent a breach from occurring.

Uniswap governance could even take this type of social enforcement to the next level by establishing an on-chain disallow/sanctions list and identifying any infringing smart contracts on that list. Uniswap could try and discourage use of infringing protocols by 1) banning users of those protocols from using its smart contracts and 2) encouraging other protocols to do the same. This would certainly be an aggressive approach, one that could have undesirable third-order consequences, such as alienating potential users. In that sense, this approach can be analogized to international sanctions, where the purpose is to target a bad actor nation-state, but the effects are felt by all citizens of that state.

Escrows and atomic transactions

In addition to improving legal enforceability, onchain mechanisms may be used to mitigate the issues raised by the Polygon case, such as escrow contracts and atomic transactions.

The idea behind the “atomic” nature of transactions is that either a transaction passes, or it does not, with no in-between states. So either Uniswap gets deployed on Polygon and the 20M incentive is implemented, or nothing happens.

To create an atomic transaction, the details of the proposal would need to be clearly defined in advance. In the Polygon case, many of the details were added after the proposal passed.

While atomic transactions offer higher accountability, they also open up various questions/problems. For one, when a custom atomic transaction is created, an audit is required to ensure reliability of the code. Furthermore, it is not always that case that all technical details are clear a priori, and if required, they would slow down the process by multiple fold. Given the inertia generated by both development and audits, it would only make sense to spend developer resources on this if the transaction is regarding a larger amount of capital.

SAFT smart contracts

In cases where tokens are promised that do not yet exist, as the case with Voltz, the licensee could be required to deploy a “SAFT” smart contract locking in Uniswap’s entitlement to future tokens. However, even this approach requires trust and informal accountability through social norms, as nothing would technologically prevent Voltz from simply deploying a different token smart contract in the future and abandoning the tokens generated by the SAFT smart contract.

D2D relationship management

When a proposal is created, one person per DAO should be appointed to be responsible for making sure the proposal is seen through and to ensure that things go as planned. In the Polygon case, “everyone” was responsible, which also meant that no one effectively was. This resulted in unclear responsibilities and information flow, and led to unpleasant events such as taking to Twitter to call the partner out. The situation was promptly addressed by the Polygon team, however the underlying issue was the information asymmetry between Polygon and Uniswap.

When partnerships involve liquidity mining incentives or other technical aspects, there should be someone appointed by the Uniswap community serving as Developer Contributor. In the Polygon case, the liquidity mining program was entirely developed by Polygon and third-party projects that provide vaults for LP’ing on Uniswap. Little outside input from the Uniswap DAO was involved in the process. While too many community members giving feedback would create a situation of “too many cooks in the kitchen” and arguably not be a good compromise, there should be 1-3 devs to be held answerable for the technical aspects of a proposal, if required.

Working in public

Beside having an appointed developer contributor per proposal, working in public increases transparency and discoverability and access to information, making it easier to organize and communicate with partners and users.

The DAO members responsible for a proposal should also be tasked with keeping track of progress and updating forum threads with the latest information for other DAO members to easily access. For instance, they should be responsible for maintaining a blog post and Twitter thread only containing critical information as the partnership develops. This also works as a marketing opportunity for the parties involved, indicating the successful development of their partnership.

Clearly these roles require time and dedication and they should be compensated accordingly by the DAO. The need for dedicated “accountability guardians” within the Uniswap community may also prompt the creation of a unit within the DAO with a clear mandate and responsibilities tasked with supporting the implementation of successful proposals.

The enforceability of these social mechanisms may also be strengthened through the combination of on-chain tools. For instance, should a proposal include financial incentives such as liquidity mining or a grant, these funds could be deposited in a multisig account on Ethereum mainnet controlled by a trusted and known set of Uniswap governance contributors. Multisigs open new attack vectors but the assumption is that the potential reputational damages will work as a deterrent for malicious behavior. Gnosis Safe can also be seen as a good trade off for on-chain transactions while still retaining flexibility in the proposal and process.

Conclusions

In this report we have analyzed three very different cases of partnerships in Uniswap:

- A live, Ethereum L2 asking to deploy Uniswap on its protocol, effectively proposing a cross-protocol partnership;

- A pre-launch middleware primitive existing on Ethereum requesting to use part of the licensed code for non-competitive goals;

- A live, alternative L1 requesting an Additional Use Grant to deploy Uniswap in a non-Ethereum ecosystem.

These cases also offered different kinds of incentives:

- Financial incentives, in the form of liquidity mining, grants to UGP, or metagovernance incentives – that is, a promise for future tokens which, in the Voltz case, are implied to have governance functions (though the details of the token function were not finalized at the time of the proposal);

- Various forms of non-financial incentives, including: technical development support, co-branding, cross-chain support, and general ecosystem benefits.

Different incentives demand different kinds of accountability mechanisms for answerability and enforceability. For instance, where financial incentives are present in partnerships and licensing requests, there should exist on-chain mechanisms to ‘trustlessly’ supplement the enforcement dimension of the weak legal accountability provided by the BSL. Analogously for non-financial incentives, the currently vague and ad hoc social accountability provided by the governance process should be supplemented with a more formalized and standardized approach to relationship management and accessibility of information to increase the answerability of the parties involved.

Importantly, accountability is not a single activity or a goal to be achieved; it is a continuous process that requires the interdependence of different mechanisms (legal, on-chain and social) in order to be effective.

©2024 Other Internet Research Institute