Introduction

The term ‘lore’ was once relegated to the domain of TV shows, movies, and video games, but has now expanded to describe the particular way that communal knowledge and group memory on the internet is constructed—through crowdsourcing and decentralized record-keeping. How did ‘lore’ come to mean what it means now? What are the conditions on the internet that make ‘lore’ so relevant? Why do people feel the impulse to turn things on the internet into lore?

The way that we engage with media on the internet has become laden with fandom energy. All narratives on the internet have become subsumed under the umbrella of ‘content’, no matter their scale or veracity. They all have the potential to gather lore, because they can all be read the same way—like fictional media franchises. This includes everyday social media activity. Performances of our online identities — which, through the act of posting, become crystallized into series of discrete media objects — are readymade targets for lore-ification. Our online identities are subject not just to mere scrutiny, but to investigation, theorization, and consolidation. Each post becomes another node connected with red yarn on the proverbial bulletin board. We construct versions of our identity that both are and aren’t ‘us’; dissociated from who we are, yet confused for us. The experience of ‘being online’ has changed so much as our networks grow denser. In a hyperconnected media environment, other people’s projections of our identities take on a life of their own. Lore, as a framework for engaging with media, is a tool for self-mythology, but can equally be a way for other people to dictate the canonical narrative of our online persona.

Parafiction and Video Games

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, the idea of ‘internet lore’ had a more specific usage. ‘Lore’ used to point more specifically to artifacts like Slenderman and other creepypastas, like Ted the Caver, Russian Sleep Experiment, and BEN Drowned (the haunted Majora’s Mask cartridge story). Creepypasta as a format, like most horror, hinges on the reader’s suspension of disbelief. Quite often this is supported by a confessional or epistolary style; many creepypastas are formatted to mimic blog posts.

Ceepypastas also often go beyond just text in order to build out the media ecosystem that the story is embedded in. Authors will create additional media (like the BEN Drowned YouTube videos) to serve as fake ‘evidence’ of their authenticity, and to emphasize the feeling of falling down an internet rabbit hole. In other words, they are deliberately framed as parafictional — fiction that purports itself to be true. Adults may read this as just a way to build up the ambiance of the story, not finding them all that plausible — but as a kid, it was much easier to take them at face value. Creepypastas felt eerily true.

The experience of my micro-generation (read: zillenials) coming of age on the internet was characterized by having to sort out what’s real and what’s fiction (see: the necessity and relevancy of snopes.com). Growing up on the internet during this time meant being exposed to a lot of parafictional media. Perhaps thats why we have now developed such a propensity for ‘lore’—it’s a model of knowledge that is able to interface with both reality and fiction.

Another valence of the word 'lore' is a particular genre of pop-science YouTube videos, screenshotted above and epitomized by creators like vsauce or reallifelore. These videos, which I might call ‘factoid-core’, package interesting facts and concepts about the physical world into the same basic format as video game lore explainer videos. Factoid-core renders the world as a collection of extremely digestible, discrete bits of esoterica, creating a perpetual ‘mind=blown’ affective stance. One reason why factoid-core has remained so successful as ‘edutainment’ is that turning history, politics, science, and geography into ‘lore’ makes knowledge acquisition about the real world ‘interesting’ [1]—akin to learning the intricacies of a fictional world that one is deeply invested in. Calling information ‘lore’ is an attempt to make it worth deeply investing in.

It’s a joke, but it’s also not. Memes like 'x lore vs earth lore'’ and ‘inanimate object lore’ proliferate because it’s funny to frame non-pop-cultural things in pop-cultural terms. There’s humor in the gap between what lore usually connotes (epic, dense narratives like the Lord of the Rings), and what its being used to describe (tectonic plates shifting to form the Himalayas). But there’s a certain truth to the humor. This impulse — jokingly or not — to call all things ‘lore’, signals that our approach to interpreting online content or encountering domains of knowledge has become more like the way that we would dive into a new sci-fi or fantasy franchise.

A phenomenon similar to the whole ‘real life lore’ thing is a particular brand of internet humor and meme-making that hinges on the idea of describing the offline world in video game terminology. Inconveniences and hardships are deemed "bugs", skills and character traits are "stats", improvements to the world are "patch updates". This meme of referring to the offline world through online terms has the same sort of ‘backwards-compatibility’ modality that referring to real life as ‘lore’ has. The logics and lexicons of the digital world we’re so immersed in (software terminology, lore, fandoms) has become our primary lens, which is then turned backwards to view the offline world.

One significant place this happens is the subreddit r/outside, in which people ask for advice or share anecdotes, but under the premise that life is like a video game. r/outside describes real life as a "free to play MMORPG with 7+ billion players". But participation in the subreddit itself is also massively-multiplayer. The entire subreddit is essentially a large-scale collaborative fiction project. The internet provides the necessary infrastructure for many projects like this. These can range from formalized structures to more ad-hoc contexts. On the more structured end of things, I’m thinking of projects like SCP, a wiki style website with user-submitted fictional reports of paranormal entities that all conform to the same canonical universe, or the 4chan /lit/ board’s collaboratively written novel The Legacy of Totalitarianism in a Tundra, or Facebook groups like the one where everyone pretends to be ants in a colony. A more impromptu example would be something like TikTok comment sections where everyone has decided to collectively play out some sort of joke.

What’s salient in all these cases is an unstated shared value of ‘commitment to the bit’, meaning that people are willing to moderate themselves to maintain the tone of the project. Even in the more formalized examples of massively-multiplayer collaborative writing, people are able to organize without a lot of top-down authority, and to collectively develop canonized knowledge through these mass exercises in worldbuilding and lore production. For instance, although SCP is strict about new submissions fitting the canon and tone of the entire project, it is moderated by other community members rather than a central body.

This mode of online participation, at its core, is lore-building, because it is centered around the crowdsourced creation of a canon and consensus on rules for engagement. Rather than asserting a distinction between reality and fiction as categories, ‘lore’ really cares about maintaining canon. People compiling lore about a video game, for example, care about true/correct details about both the fictional universe as well as the real details of the video game’s development or impact on the culture. Things like fan theories can also become canonized in a way, even though they are technically unconfirmed or speculative knowledge. They can be repeated and discussed enough to become staples of the community culture. Truth is only important relative to the lore object, whether that be fictional media, or the real life of an internet micro-celebrity.

r/outside is a somewhat siloed example of this, but in general, the language of video games has been folded into internet speak. One could even argue that the vernacular usage of the word ‘lore’ originally referred video game worldbuilding, before now being used in broader online contexts.

Many video games have both explicit and implicit worldbuilding. Explicit worldbuilding consists of readily available information about the fictional universe as told by official, authorial, top-down sources. Implicit worldbuilding is done through the creation of lore, which, critically, is authored both by the creators of the game and the players. This lore is information that the official authors have perhaps left clues about within the game, but have not explicitly spelled out yet, which is then expanded upon through things like fan theories and speculation. Motivated players might not consider the game complete until they find all these hidden clues to know all the lore. Crucially, one can also deep dive into the lore online, pieced together by the fandom of the game.This activity becomes an extension of the game proper.

Video games manifest a completionism mindset that has translated to other contexts, becoming a driving force behind what makes lore compelling. Even outside of the format of video games, lore gamifies the act of media consumption, like the way watching a movie with lots of hidden details in the background feels like a scavenger hunt, or how piecing together details of a youtube vlogger’s personal relationship feels like solving a mystery. Lore is compelling because of the unexpectedness of where and how one encounters it. It feels like an accomplishment collecting all these little bits of information in order to gain insight on a narrative. This pattern of obsessive and game-like media consumption became the norm, especially in the context of the dominance of nerd culture that happened in the late 2000s / early 2010s. It’s led to a generation of people, primed by video games and movie franchises, that expects all media to have easter eggs waiting to be found.

The difference, of course, is that most video games are closed systems — it is actually possible to get to 100%, to explore every corner of the ‘world’ that was built, to check every treasure chest, to find every easter egg. But in lore beyond fictional media, it’s not possible to know the whole story, even though it often feels as if the story can be solved.

Fandom Energy

Our current media environment has become conducive to gamified media consumption by framing information and entertainment as ‘lore.’ This environment emphasizes the social configuration of the fandom, which has become endemic to online life. The logics of fandom seem to permeate everything. Fandom energy is latent wherever there is sufficient density of social interaction and lore-creation around some core media object.

When fandom communities on the internet develop, it doesn’t take much for lore to be generated about the community itself, creating a ‘fandom of a fandom’. This fandom meta-lore very easily becomes intertwined with the lore about the object of fandom. The two interact with and influence each other, creating a positive feedback loop between the culture of the fandom and the object.

For example, the reality TV show The Bachelor has a large online community that exists in numerous places — Reddit, TikTok, Instagram, forums, and podcasts. One such podcast, Game of Roses (GOR), began as a podcast analyzing the show and its players through the lens of sports analysis. The project of GOR is to taxonomize and apply statistical analysis to various aspects of the show, like identifying the 8 main types of limo exits and their success rates. As the GOR podcast has grown, it has become more and more interested in actually influencing the show. The hosts have even outright said on their podcast that they have secretly coached contestants that were on the show. There have also been several instances where people from the show use terminology that GOR came up with, meaning the lore that GOR has generated had made it all the way to official channels of the franchise. Game of Roses, being firmly situated within the fandom of the Bachelor, discusses and analyzes the lore that comes out of the show, but is now also significantly affecting the source media.

GOR gives us an example of the ways a fandom might affect the original media, but the inverse happens as well. Celebrities have increasingly become aware that participating in their own lore-making is a valuable tool for building a following. Taylor Swift, for example, is notorious for generating lore, putting easter eggs in everything she does, and reading and playing into fan theories about herself. She does this both in the ‘text’ of her songs (see: the fandom’s obsession around the Betty/August/James lore in the album literally called folklore), as well as in her activities surrounding the music, like marketing campaigns and interviews. Fans pore over every word Taylor says in interviews because she often embeds clues to her future releases in what she’s saying. She constantly references her older work in new lyrics she writes, creating linkages that fans find fun to piece together. Swift’s fans also mirror her well-known love of numerology, making predictions by adding and subtracting significant dates.

The thing is, while comments like the one above seem insane (as the poster acknowledges), they aren’t totally unprecedented, because these are exactly the kind of easter eggs that Taylor is notorious for leaving.

Over the past 13 years, Swift has perfected the pop culture feedback loop: She shares updates about her life and drops hints about new music, which fans then gobble up and re-promote with their own theories, which Swift then re-shares on her Tumblr or incorporates into future clues. […] "I've trained them to be that way," she says of her fans' astute detective work. Swift is a pop culture fanatic herself […] and has an innate understanding of the lengths her audience will go to be a part of the original creation. "I love that they like the cryptic hint-dropping. Because as long as they like it, I'll keep doing it. It's fun. It feels mischievous and playful."

— Alex Suskind on Taylor Swift for EW

The numerology thing, when it doesn’t take over on its own, I sort of force it to happen. There are 16 tracks on Folklore, there are 15 tracks on Evermore. Add ‘em up, what do you get…? 31. In my mind, it’s just the opposite. It’s just 13 backwards

— Taylor Swift during her appearance on Jimmy Kimmel, December 2020

Taylor Swift, by tapping into and playing into the lore that has generated around her, has found a way to modulate moments of collective disappointments with moments of collective reward. It’s exactly why gambling is addictive. By spending all of this fannish energy towards speculation, even if you don’t uncover any magic numeric messages right away, the sunk cost of time, energy, and emotion makes the eventual appearance of an actual connecting-the-dots moment that much more euphoric. Through selectively choosing when and how hard to play into fan theorization, Taylor has her fanbase not only engaged, but loyal and invested in the collective project of the fandom, to the point where Swifties have garnered the reputation of being insane, rabid internet detectives.

The internet is now in a state in which fandoms and communities are motivated to generate, document, and circulate lore about the slightest crumbs of content. Fandoms hold an incredible undercurrent of potential energy, and viral TikTok or Twitter moments are the release valve. In the early days of internet culture, virality felt like an anomaly, a quasi-miraculous event requiring countless synchronicities. But now, as online networks become denser and denser meshes, virality is almost the rule, the primary protocol for online interaction. Latent fandom energy causes affective communities to coagulate around any sufficiently interesting piece of content, becoming the engine behind the increasing occurrence of viral moments.

This energy has been intentionally instrumentalized by media producers on a wide variety of scales. Producers of empire-like media properties such as the Marvel Cinematic Universe have long realized the immense amount of capital at stake in generating lore through cross-over events, easter eggs, and end-credit scenes, because it makes people deeply invested in their intellectual properties. There is now less of a boundary between the actual media product and the whole secondary media production around it (reviews, analysis, fan theories, explainer videos, fanart) since media producers are not only willing to engage with all of this secondary machinery, but make lore generation one of their primary marketing techniques.

Thus the malleability of ‘lore’ as a category has become extremely useful. It can be applied to fictional media, gossip networks, and crowd wisdom, as well as information from centralized, ‘official’ sources. Lore as a framework for consuming media is useful for navigating complex, non-linear knowledge domains because it is aggregative and interpretive, rather than universal and objective. Everything has the potential to become lore — from the Himalayas to Taylor Swift. And often, this is what content creators want — they want to be lore-ified because they want people to be invested in the project of actively excavating their lore, creating engagement that’s deep and sustained, rather than shallow, passive consumption. But what happens when individuals become subject to the lore machine against their own will?

The Wonderland System

In the last week of 2021, my FYP became saturated with TikToks about ‘The Wonderland System’. An 18-year-old gained a lot of notoriety for making a series of TikToks about their dissociative identity disorder (DID), documenting the intricacies of their alternate identities (called ‘alters’, collectively called a ‘system’) and the intricately detailed inner world that these alters inhabit. A fandom-like fervor of secondary content/discourse quickly developed around this person, roughly divided into two main levels of discussion. One level of discourse took what OP described at face value, and speculated about other details of the inner world and the alters. The other level of discourse consisted of arguing about ‘fakeclaiming’, and debating the ‘outer world’ details of OP’s life and mental illness.

The spread of the Wonderland System TikToks is endemic of a larger, politicized discourse about teenagers self-diagnosing and potentially faking symptoms of Tourette’s and DID. With the idea of sociogenic mass mental illness prominent in the discourse, people felt justified in using the language of pathology and diagnosis to suss out OP’s moral positioning.

Most striking to me was that everyone felt compelled to keep referring to this discussion, plus other information about the Wonderland System, as ‘lore’. But the categorization of all of this as ‘lore’ became controversial in its own right. Multiple commenters expressed discomfort about framing OP’s content this way, begging the question: in a media landscape where all content has been flattened to the same level, what does it mean to turn someone’s real life into lore?

The word ‘lore’ was used in relation to the Wonderland System to refer to two different levels of information. The first was ‘in-universe’ lore, consisting of details about OP’s system, the inner world, and the alters. The second was the meta-fandom lore developed by the affective community that formed around these TikToks. This includes things like the lore of how this person became viral, theories about whats actually going on with OP, their possible motivations for posting, fakeclaiming discourse, etc.

Because of these two levels, the same piece of information could be framed through these two different ways: One could either say, ‘OP has 200+ alters that all co-mingle in the inner world’, or make a statement like ‘OP is claiming to have 200+ alters and presents them in a way that seems inconsistent with the textbook definition of DID’.

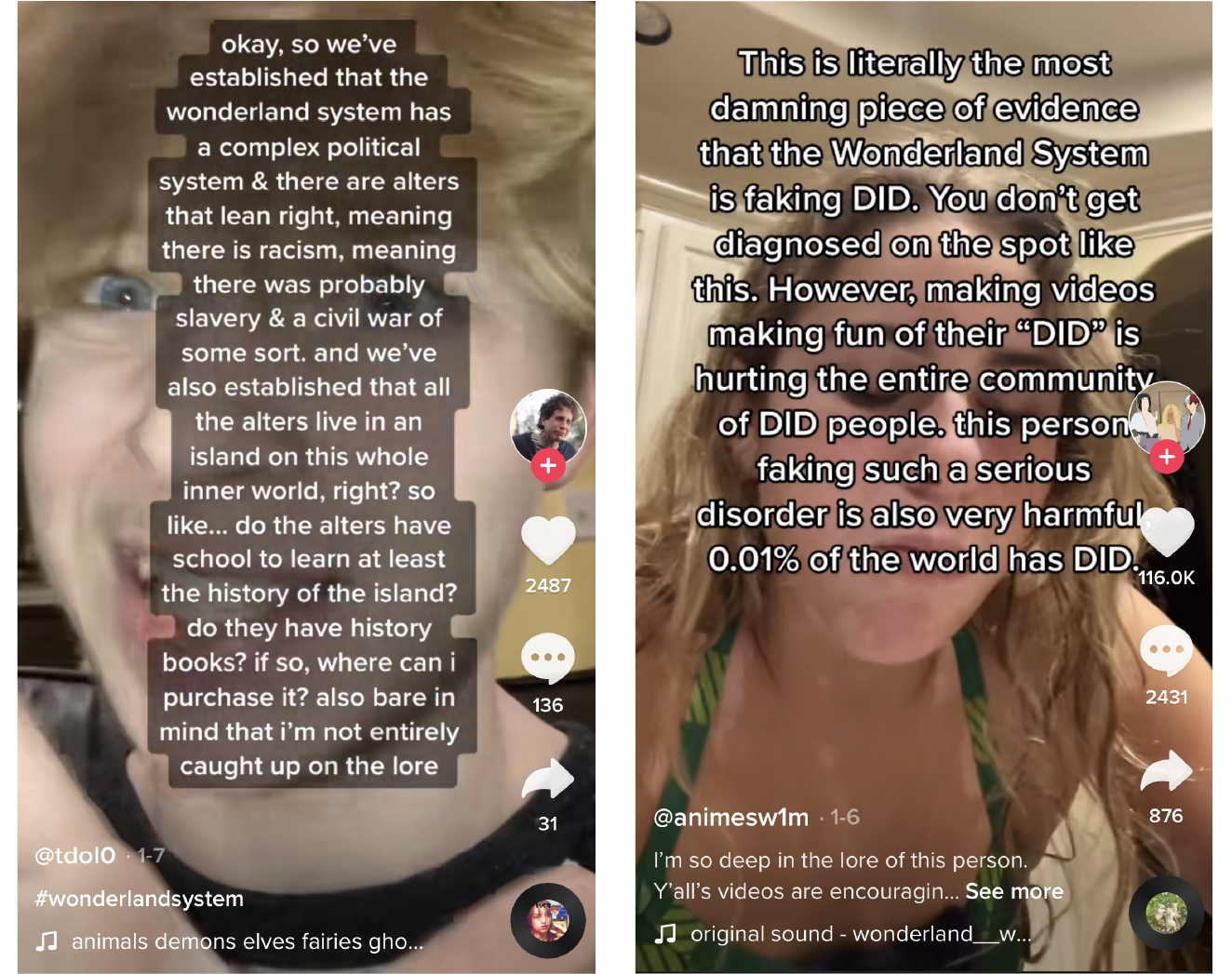

Left: Lore about the ‘text’ — details and speculation about the inner world. Right: Lore about the fandom around the text.

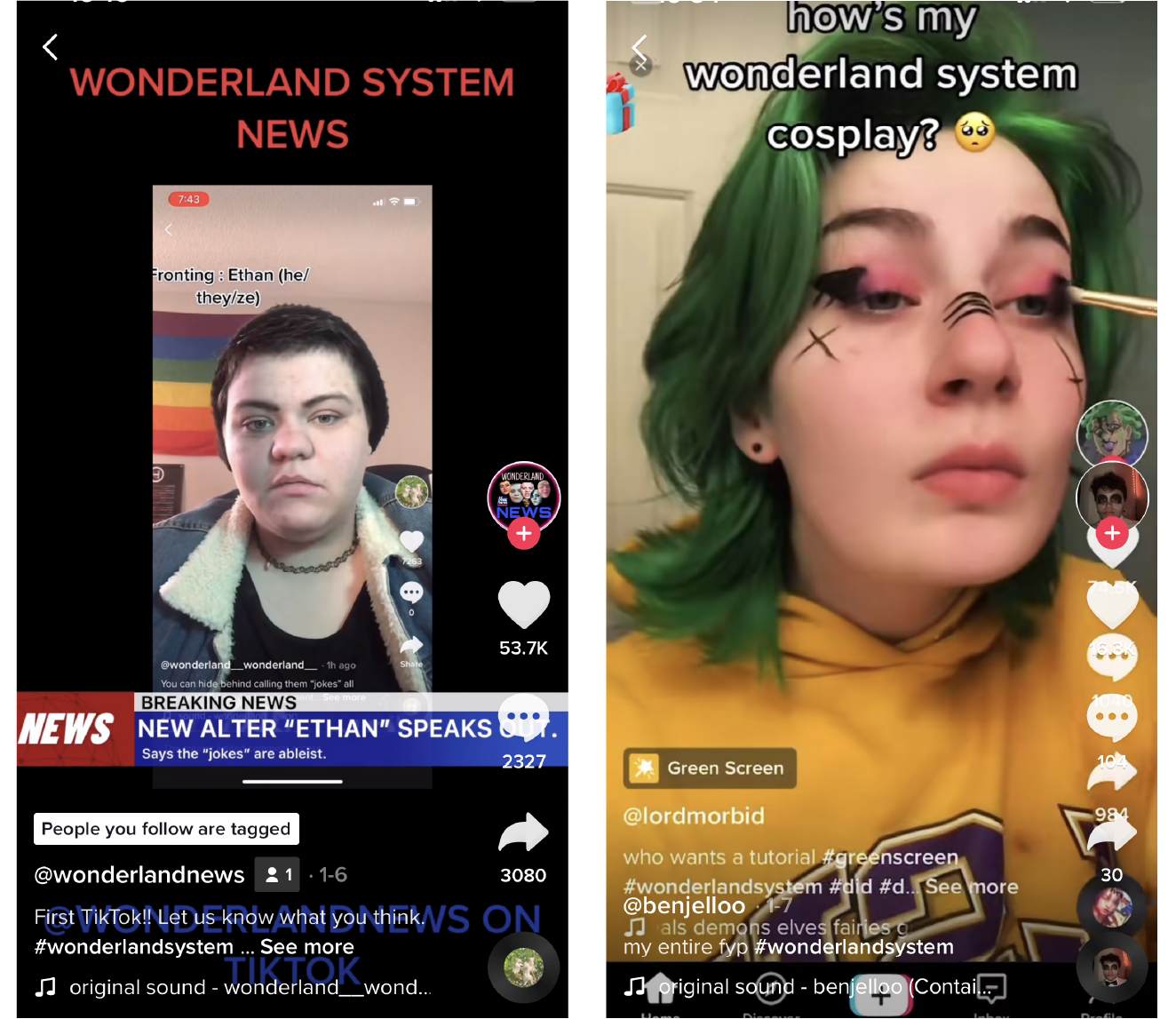

These two levels of lore became especially blurry because of the main question that characterized all of the discourse: to what extent should followers of this saga treat OP’s inner world as fiction? Some TikTokers argued that it is fiction insofar as it is literally made up and in their head, but others thought that it could be ‘real’ in that all of this might actually ‘feel real’ to OP. Those who legitimately tried to engage with OP’s content in good faith took the inner world at face value, and were perhaps genuinely interested in details like the social dynamics between the various alters. But for the segment of the audience that clearly didn’t believe OP, part of the joke was to adopt the affect of fandom. This included activities like compiling a fandom.com wiki containing all the information about the different alters, creating google docs, and writing fanfiction. There were even multiple dedicated accounts parodying the formal language of local news coverage, to report on the wonderland system (e.g. @wonderlandnews). But even though the audience was treating OP as a celebrity, all of this fannish activity felt like it was being done in bad faith. These people weren’t actually fans of OP. Celebrity functions as a label that tells us whose public personas have been sanctioned for commodification. Which is why it feels much more morally acceptable to engage with, say, Harry Styles x Louis Tomlinson fanfiction, with the Wonderland System. Real person fiction, which is already controversial, feels even more egregious with people who go viral so fast that they bypass a more traditional onboarding to ‘celebrity’ status.

A further complicating factor: the structure of the inner world described by OP had obvious references to The Hunger Games and other dystopian YA franchises. To some people this was enough proof that it was fake. This was evidence that OP was morally wrong for de-legitimizing DID, and thus up for grabs to be meme-ed about. But this isn’t necessarily true. The only thing it indicates is that OP grew surrounded by and absorbing media that naturally lends itself to lore. It stands to reason that forming one’s identity in such a lore-filled media environment would lead to the production of a lore-filled ‘inner world’. The content that OP was posting felt like self-mythology, but when the mythologizing started being done by strangers, things clearly started to feel wrong to them.

On January 6th 2022, OP posted their last video and left TikTok for the foreseeable future. In this video, OP addressed the storm of discourse spiraling around them, accusing their fans of bullying and ableism, and re-iterating the legitimacy of their diagnosis by directly addressing the fake-claiming discourse. One part of the video addressed the widespread use of the word ‘lore’:

[…] “side note: calling it ‘lore’ is fucking disgusting. It’s a disorder caused by severe or repeated childhood trauma. How is it funny to treat it like its a fucking video game or a piece of media? you guys are gross.” […]

OP was distressed over the collaborative lore-building around their interiority, which they did not think of as being collaborative at all. To OP, the audience not only rendered their interiority in fictional terms, but also infringed upon the self-made canon of their identity. It’s easy to imagine how this objectification of their mental illness might feel incredibly invasive. That said, I don’t think OP realized that making videos about one’s mental illness literally objectifies it. The Tiktoks are discrete pieces of media that other people can string together into their own narratives. Any online expression of our identity has the potential to be turned into bits of lore, and thus untethered from individual authorship. While that’s not necessarily anything new, intense personal loreification is happening more frequently as internet users get more densely connected. Although many people engaging with this content and creating TikToks around it were doing it as a joke, the impulse to turn it into lore, and to label it as such, was immediate and explicit. This impulse can’t be fully attributed to individual actors; it’s a function of the network. Lore is a byproduct of the way that social media platforms have shaped the way we consume and think about content.

So much of the Wonderland system discourse was centered around the One Big Question: Was OP valid? Even OP acknowledged that their inner world was, of course, ‘made up’; it purely existed in their mind. But to OP, that was besides the point, and had no bearing on the validity of their diagnosis. There’s just truly no way of knowing how ‘real’ their mental illness is, or what ‘real’ even means in this context. This impossibility of verification is inherent to nature of psychology and subjective experience. Even if their experience of their own inner world is ‘real’, other people can only access that experience through an account. The ‘primary document’ of a psychological experience is inherently inaccessible to others and can only be accessed through some form of mediation. From the audience’s point of view, there is no functional difference between these TikToks of DID alters and TikToks of people performing skits and embodying different characters, except for how deeply, if at all, the poster identifies with these characters. But who gets to arbitrate the validity of this identification? Posting, in itself, is a dissociative act. Even when we perform a ‘true’ or ‘default’ version of ourself on the internet, the act of posting is still an act of projection. We send out a certain image of ourselves that, once posted, is untethered from our flesh and blood body. Does that image still belong to us, or does it become part of the ether?

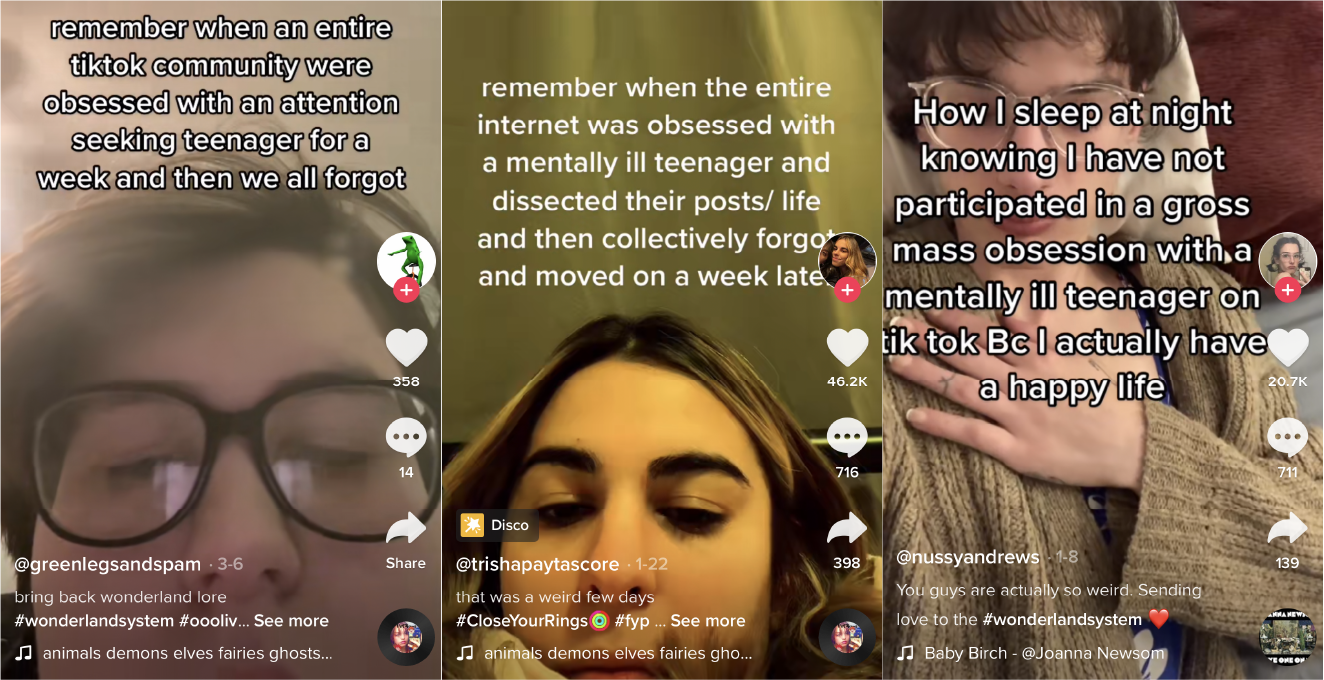

After OP went on indefinite hiatus, the only posts created about the Wonderland System were postmortem adjudications. My last encounters with the Wonderland System were through TikToks that were created weeks to months later, that simply asked people to remember what had happened.

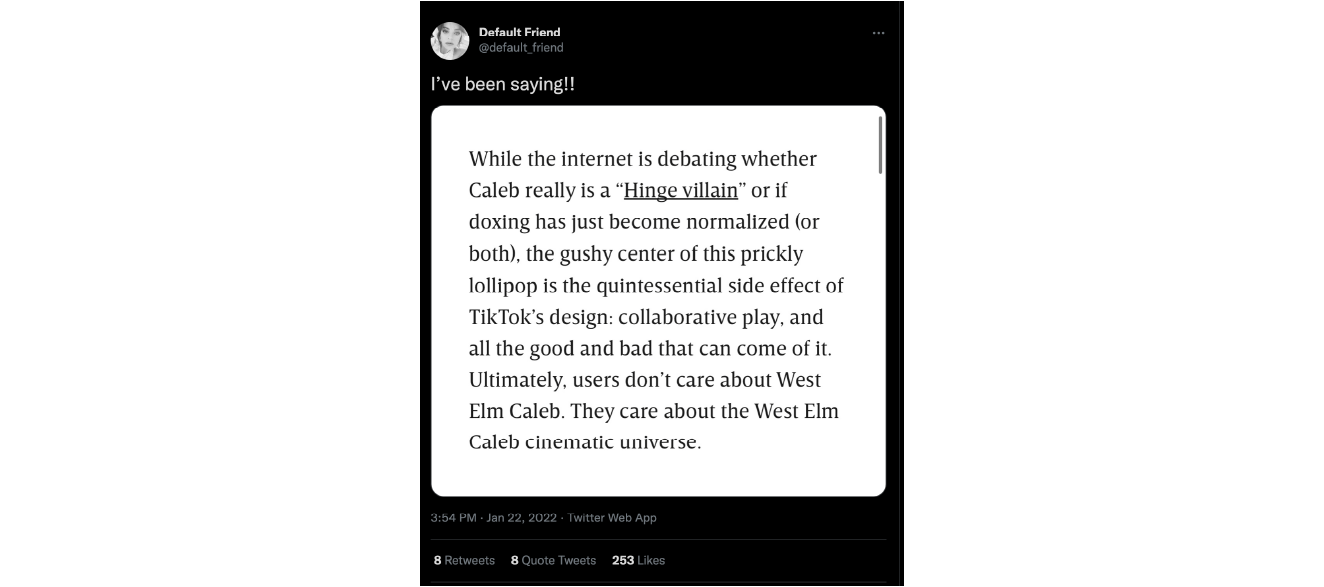

The Wonderland System went viral around the same time as similar TikTok frenzies like ‘west elm Caleb’ and ‘couch guy’. When considering these events in context with each other, the ‘collaborative play‘ (as Default Friend phrases it in the above tweet) aspect of TikTok really becomes apparent. The 1 to 3 minute time limit to TikToks forces narratives to be broken up into small pieces. The algorithm that serves these small pieces creates game-like adversarial friction to finding and metabolizing all of these pieces, and features like stitching and duetting encourages adding your own take to the larger bubble of content that is being built up. Then, when it reaches critical mass, opinions crystallize and a narrative emerges. The final bits of analysis might happen on other platforms, whose perceived distance and difference in tone allows for a more removed and conclusive take. The event then exists in pieces of media that sink to the ocean floor, able to be dredged up if one chooses, but never resurfacing en masse on their own again. But at the end of it all, there still remains the real person whose entire life had been arbitrated by millions of strangers.

What happened to the Wonderland System reveals the dark side of affective communities united through the common goal of ‘solving’ something. These ‘meta-fandoms of solving’ spiral out of control and lose sight of the offline stakes. Creating Wonderland System lore gamified the content OP posted, but the harm done to them was real. The obsessive, internet-detective affect that these platforms engender compel us to ‘solve’ someone’s interiority, as if it were a finite world to be taxonomized, catalogued and documented. But we are always outside of these worlds, looking inwards. Our experience of other people’s online identities can only be constructed through a gestalt of their posts, which may or may not actually align with their offline identity. Studying whatever lore that is created from this construction, then, might be useful to gain insights about the world that the affective community has constructed around the person, but doesn’t necessarily tell the whole story about the actual person.

Lore, as a knowledge framework, has been applied at vastly different scales, from the geological and historical (reallifelore), to large media franchises, to fandoms, to celebrities. But when ‘lore’ is applied to the scale of an individual’s interiority, at first participating in the lore feels fun, but then people start getting a bad taste in their mouth. At larger scales, even at the level of celebrity, one could argue that the scrutiny that comes with being turned into lore is just the price of fame. But for people like the Wonderland System—or for any of us, really—did we sign up for this type of scrutiny by strangers just by being on these platforms? Do we deserve it? Do we consent to it?

Or is this just a feature that we have to implicitly accept? Terms and conditions say yes, especially on platforms like TikTok where the algorithm is designed to serve your content to strangers. The previous notion of a coherently branded online identity made sense in the context of platforms like Facebook and Myspace premised on offline relationships. But now that platforms serve content to a broader, more amorphous network of internet strangers, our identities are somehow both more fluid, yet more vulnerable to being calcified into forms that could spiral out of our grasp. Despite our best attempts at controlling our stories, any trace of self-mythology can be hijacked and re-canonized into lore that belongs to the network. If you try to make your online presence more lore-worthy in order to be legible to these platforms, you could end up falling asleep at the wheel of the algorithm. You might even wake up one morning to find that the fancam you liked to imagine watching you has suddenly become real.

1: See Sianne Ngai — Our Aesthetic Categories