Introduction

When citizens can only meet in public for certain purposes, they regard such meetings as a strange proceeding of rare occurrence, and they rarely think at all about it. When they are allowed to meet freely for all purposes, they ultimately look upon public association as the universal, or in a manner the sole means, which men can employ to accomplish the different purposes they may have in view. Every new want instantly revives the notion. The art of association then becomes . . . the mother of action, studied and applied by all.

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

Some guy named Alexis (above) wrote a canonical analysis of the U.S. political landscape. Central to his exploration was the role of voluntary associations and the all-encompassing but also decentralized, microscopic nature of American government. Politics cascaded from federal institutions to hyperlocal spaces, and flowed (in some ways) bottom-up, spawning an ecosystem of commercial, civic, religious, and political groups all in conversation and competition with one another.

Tocqueville’s ideal of free association, though it’s been denied by antidemocratic forces throughout U.S. history, has often been held up as a gold standard for those who wish to cultivate a vibrant civic sphere.

While this ideal may appear static, the nature of association is always evolving in response to changes in the media environment. The last decade of digitization has brought especially notable transformations to our ways and means of gathering. Web2 software wove its way into daily urban life, intermediating the relationship between citizens and their cities. Then, a powder keg. Covid pushed this process to its logical extreme: Sequestered from each other for public health reasons, we’ve been unable to “meet freely for all purposes.”

Instead, we’ve been cooped up in Zoom grids, bound by the physical and psychological limitations of virtual associating. For those with the means to weather the pandemic inside (and those who’ve survived), the commons has moved almost entirely online. Many have gravitated towards new visions of how we ought to relate. Zoom happy hours, sure, but also tokenized quests to overhaul community organizing and urban planning, with Discord serving for many as the new definitive public forum. Not to mention the movement to build new cities from scratch, backed by a huge influx of capital from prominent technologists (howdy, Vitalk) and investment firms.

Existing civic spaces didn’t die, though. An incumbent on this front, largely unassuming to the Very Online, is the neighborhood association. You’re probably sleeping on neighborhood associations, tbh—or you’re sleeping within one’s bounds without knowing it. These orgs (also known as civic associations, citizens associations, and community associations) are a p2p “government” outside of The Government, a vintage decentralizing force in which volunteers take responsibility for their neighborhoods and administer local public goods. They cast members in the role of “participants” rather than “end-users,” giving them increased agency over the built environments they call home. Associations have ridden out the pandemic via webcam and tools like Twitter, Zoom, and email listservs. While many of us work to build globally decentralized organizations, neighborhood associations have focused their efforts on maintaining collective agency in the form of a localized “we.” Their wholesale virtualization under Covid presents a valuable opportunity to take stock of this institutional form and study how it functions as a medium for cultivating civic engagement.

What role have neighborhood associations traditionally played in local governance? What are the civic possibilities afforded by neighborhood associations, and how do these groups differ from fully digital social technologies? How did local associations adapt during the pandemic? And in their moment of reinvention, what lessons have they learned about the art of association?

Other Internet is no Tocqueville—only one of us grew up in France, mdr—but we set off on a smol ethnographic quest to answer these questions. From sea to shining sea (mainly Washington D.C. and Seattle), we interviewed the leaders and maintainers of 18 associations:

Retired grandfathers, political science professors, block party aficionados, armchair historians, new mothers, amateur picklers.

Chatterboxes, homebodies, busybodies.

We chose these cities because we wanted to learn more about what was going on in our own backyards, but our analysis will likely resonate with civic orgs wherever they happen to be located. Our eclectic group of interviewees felt called to participate in local governance for many different reasons. They all shared textured stories of the often overlooked but important work of their associations, as well as how they grew, shrunk, struggled, and adapted during this digital tsunami.

Part 1

Zooming out: How web2 turned citizens into “end-users”

In order to understand the value of old-school approaches to associating, it’s helpful to keep in mind the ways in which digital technologies have subtly but substantially reshaped our civic identities.

Back in the late 2000s and early 2010s, smartphones offered a (now difficult to remember) promise. These devices were going to enable mass democratization and turn everyone with an internet connection into a productive member of civil society. Technologists and politicians pointed to the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street as early examples of the systemic change that would inevitably be sparked by web2 platforms. But as Zeynep Tufecki details in Twitter and Tear Gas, digital-first movements are often fragile and fleeting at their core. Viral Facebook and Twitter events could bring people to the streets, but couldn’t build deep organized connections quickly enough, or lasting trust among those who just met each other. Furthermore, the surveillance backdoors built into these ostensibly democratic tools are used by the state to target and arrest protestors (as seen in popular uprisings throughout the social media era, including the summer 2020 Movement for Black Lives).

Despite their shortcomings, Web2 services began to function as the container of the body politic. They adopted many of their foundational metaphors from analog urban life: forums, public squares, posts, newsletters, bulletin boards, platforms. FB Groups, Nextdoor, and Citizen worked to wire neighborhoods together and build “stronger communities” (Mark Zuckerberg)—often through vigilantism as the main communal activity. Meanwhile, government agencies like United States Digital Service and non-profits like Code for America brought the logic of corporate user-experience design to the public sector, recasting citizens as users. Civic engagement would be as easy as “See Click Fix,” as one local governance app put it.

All told, “e-democracy” advocates (gotta love early 2000s terminology) appified civic engagement, slowly building up the City as a Service. Municipalities began importing the mental models of software into the sphere of civil society: What is a tax if not a yearly subscription to government services? What is a city if not a big computer? As Jennifer Shkabatur wrote in her 2011 paper “Cities @ Crossroads”:

The discrepancy between the democratic theory of participation, its implementation online, and the surrounding rhetoric is caused by the fact that architects of digital platforms mistakenly apply the terminology of participatory democracy to an unrelated phenomenon. Instead of bringing to life the participatory vision of cities, as their rhetoric suggests, they in fact follow the consumerist model of city-citizen relations . . . Citizens are treated as consumers, who may occasionally contribute their professional skills or local knowledge to improve the service provided by the municipality.

When our public forums become forms, civic engagement becomes about efficiency, information sharing, and data collection. Our urban spaces start to feel extractive (see: Sidewalk Labs or even New York’s WiFi kiosks). What’s emphasized is our ability to provide legible data to planners and elected officials. There’s a contrast between the interfaces available to the “citizen-consumer” and the possibilities afforded by membership in a neighborhood association. Associations foreground collective stewardship, historical preservation, community celebration, continuous commitment. They are a social technology worth studying because of the way they supplement digital efficiencies with neighborly agency and conviviality.

Going local: the meat & potatoes of neighborhood associations

“Neighborhood association” is a generic term for a group of residents living inside a geographically bounded area who come together to do… something. Anything, really. When it comes to “types of organization,” the neighborhood association is about as basic and barebones as it gets.

The membership criteria are simple: You just have to live or work in bounds. Some, but not all, associations ask for yearly dues (usually somewhere between $10–$25). Associations tend to be incorporated as a 501(c)(3) or 501(c)(4), a legal entity for the “promotion of social welfare and the common good of the community” (IRS) and they function as social infrastructure for the neighborhood, more durable and institutional than the informal circles and scenes that come and go. Unlike issue-specific advocacy groups, they’re more of an empty vessel that neighbors can wield toward whatever ends they care about. Robert J. Chaskin describes them as a middleware of the political system, operating in the “interstitial space . . . betwixt and between the state and civil society, in which they have a foot in and a foot out of government, sometimes effectively wielding direct influence on public decision-making and resource allocation and representing the interests of the neighborhood” (2013). At their best, associations are a forum available to those who want to take collective action at a level that’s often too small to be adequately seen by the state.

Often confused with homeowner’s associations (though they are in reality quite different), neighborhood associations exist all over the world, and their organizational design varies by location. They usually consist of a listserv, a board of directors, a bank account, and a body of members, each of whom can vote on proposals and put forward their own. Though associations sometimes have a reputation for being stiff and stodgy, they usually prefer “Bob’s Rules” over Robert’s Rules, as Kalvis Mikelšteins of NYC’s DUMBO Business Improvement District put it:

Bob's Rules… I guess it’s the alternative to Robert’s Rules of Order, like “We’re gonna do Bob’s Rules!” I’ll ask, “Does everybody agree?” and if everybody nods or everyone says yes, we don’t have to take minutes, we’re all normally going along. And if it feels like a conflict, then you have to start elevating the amount of rules you use, and that's how you get to Robert's Rules of Order where everyone's sitting around going, “Well, I motion this” or “I second this!”

Neighborhood associations not only decentralize the power of local government: They’re quite decentralized internally. During the course of our research quest, we found that associations typically have several committees, each of which focuses on a particular issue area. Their activities may sound quotidian or workaday, but that’s because they’re the tasks that help bring a neighborhood to life:

i. Land use & improvement

Should the empty lot next door become a baseball field or a dog park? Where are bike lanes, crosswalks, and speed bumps most needed? How should the neighborhood get redistricted? What kinds of businesses should operate here? What should go in the pit that was left behind when Safeway exited the neighborhood? How do we stop a highway from cutting through our homes?

When it comes to simple things like fixing potholes and emptying trash cans, 311 services and civic social media can help get things done relatively efficiently and quickly. These platforms help smartphone-bearing citizens become better data collectors and reporters. But thinking more imaginatively about the local built environment (and how it could evolve) requires careful practitioners of the “art of association”. Committees devoted to beautification, development, and community gardening gather together neighbors, real estate companies, business owners, and city officials into an expansive conversation around how nearby land gets used.

Susan Volman joined D.C.’s DuPont Circle Citizens Association “back in the old days” after she found out about it through the local paper. Their group, which counts several hundred members, is located in a neighborhood that has undergone extensive development in the past few decades. Susan said associations provide an organized way for residents to have a seat at the table:

The city and developers have their objectives; they care about moving 20,000 people through every day. But there are 20,000 people who live here. We have to balance the objectives, and preserve our neighborhood as a place where people want to live and not just want to visit. Which puts us at odds with business people sometimes.

Melissa Yeakley, president of a Washington D.C. neighborhood association called Friends of Kingman Park (FOKP), joined because she’s always been interested in community outreach and civic engagement. She told us a story of how her group transformed a vacant lot into a garden:

There was an inner plot of land that was kind of a junkyard, used as a parking lot for football games at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium, and FOKP worked with the city to pay back the taxes on this land. Because we are a 501(c)(3), we only had to pay $1 . . . now we have 100 raised bed plots, garden parties, movie nights, a harvest festival. It’s a cool space; a ton of work, but a lot of people are interested. Having that space gives you endless projects.

ii. Scene making & event organizing

How do we promote intergenerational relationships between neighbors and help residents get outside their social comfort zones? What’s the best way to celebrate important holidays as a community? How can we support local farmers, artists, and musicians at our block parties, markets, picnics, and charity drives? How do we make relationships strong enough to support civil debate when controversial issues inevitably arise?

Web2 social media promised to help connect us with like-minded individuals who share our interests. It sorted us into “lookalike audiences”, composed of other users deemed by machine learning models to be demographically similar, resulting in echo chambers and increased polarization. We found associations taking a different approach to organizing communities. Their goal is not just to help residents connect with compatible would-be friends, but to strengthen the social ties between everyone inside their geographic bounds. Especially neighbors who would not otherwise cross paths.

Tricia Duncan is the former president of Palisades Community Association (PCA) in Washington D.C.. At 1,800 members, it’s by far the largest group we spoke with. Tricia championed the lively culture of event organizing in her neighborhood:

Our biggest thing is events. We ended up modifying events for Covid. We did a lot because people needed to get out of their house. We did this thing called a bear hunt where people would put their stuffed animals in their windows and kids would walk around and point them out. Everyone was really excited . . . We do an extravaganza the week before Easter, and it’s this huge egg hunt with field games at the park. We also do a cookout at the firehouse every year, usually around Halloween. Plus a potluck and an Octoberfest.

Melissa of FOKP echoed Tricia’s enthusiasm, saying:

Bottom-line reason FOKP exists is for neighbors to get to know one another and practice living in community, whether it’s through… clean-ups or peace walks. When neighbors know each other, we feel more connected and take steps to invest in our community.

iii. Grantmaking & resource allocation

Which local schools, artists, and mutual-aid efforts should receive our micro grants? How do we make sure the community has a say in how our resources are allocated? Which of the smaller groups in our neighborhood need a fiduciary entity to hold their money? Which local students should receive scholarships?

Crowdfunding tools and online polls offer a way for users to direct their funds to a predetermined cause or set of causes. Associations allow neighbors to pool resources together before they know what they’re going to do with them, and they facilitate collective conversations about what’s needed at the local level. Relationships come first, then possibilities, then actions. These groups are well-positioned to fund hyperlocal initiatives that would otherwise escape the notice of tax-funded city services. And residents are given the chance to directly manage shared resources as part of a larger “we.”

Susan Volman of D.C.’s DuPont Circle Citizens Association told us:

Early in the pandemic we gave $1,000 to various organizations to feed people and take care of people’s health . . . we gave a large grant to the theater for renovations, to a community outreach program, to the school’s parent-teacher association, and other small projects for the schools.

iv. Information circulation & lore preservation

How should we keep neighbors up to date on what’s going on in local government? What’s the best way to surface resources that are difficult to find online? What should we include in the monthly newsletter, and who’s going to distribute it? How can we preserve the stories of older residents and pass them on to newcomers? How can residents easily learn about what the neighborhood was like before they moved in?

While local government’s adoption of social media has in many ways proved transformative, these sites have also spawned toxicity and pettiness. Users, especially older folks, feel overloaded by information and unsure of which sources to pay attention to. The affordances of FB, Twitter, Nextdoor et. al. also make it difficult to preserve or canonize local history. The feed has the memory of a goldfish, always surfacing whatever topic happens to be hot right now.

We found associations curating relevant resources and creating local networks of trust. They also collect personal stories, creating digital and physical archives of the histories of their neighborhoods. Learning more about the local past gives residents a more expansive sense of what’s possible, and of their own agency.

Stan Benton helps maintain the Penn Branch Neighborhood Association in Washington D.C. He got involved because he felt he could run the operation with “less drama.” Stan shared how his association helps knit the neighborhood together:

I love that neighborhood associations have continued small town local information sharing. But it’s work… Each block has one person in charge, mainly to distribute information and keep tabs on if anybody needs assistance with anything… We have roughly 27 block captains, and that’s their gig: to help keep everybody in touch.

When it comes to lore preservation, William Emmet, a retired mental-health policymaker and president of the Mount Pleasant Village association in Washington D.C., told us about a history project his group recently worked on:

We made a video series drawing on expertise from a member… The neighborhood is made up of people with fascinating stories. A number of people have been involved in the Peace Corps or have had very interesting careers, and many people are looking back and are willing to talk about them… It’s a terrific record of many lives and of what people did over the last 30–40 years in this country and the world.

v. Advocacy & accountability

How do we hold our elected officials to account? On which issues should the association testify at the city council? How do we make sure residents take full advantage of constituent services? Which of our members should run for local office? How do we create forums that put local candidates in conversation with each other and our neighbors?

Web2 platforms were touted for their ability to connect us directly with our elected representatives. Though they were supposed to offer increased transparency and accessibility, the connections they create between local politicians and constituents are relatively shallow. Online feedback forms, comment sections, and “customer surveys” are easy to ignore and don’t allow for the sort of relationship building that’s only possible at the hyperlocal level. Associations are effective at facilitating genuine dialogue between residents and public officials. They also enable many voices to speak to elected officials as one institution, which amplifies the concerns and desires of individuals more effectively than @replying to official government accounts.

Jimmel Sanders, president of the Deanwood Citizens Association in Washington D.C. joined after she moved to the neighborhood in 2008 and wanted to “figure out where [her] talents can be helpful.” She said one of her group’s main functions is to figure out what residents want to see more of:

Businesses are going defunct so we have to advocate now for what stores we want and ask what are the components of a healthy community? What are the service providers? What are the things that healthy people need to live? Our core function is to be that belly button—that center for community activism.

John Capozzi, a fiery member of the Hillcrest Neighborhood Association in D.C., has been involved in the local governance scene for north of 30 years. He emphasized the powerful role associations can play in holding local governments accountable:

Civic associations have to build the connection between the local representatives. Invite people that are in the government that you think can help you and press them on it. If you get mad enough at any commissioner you can probably get rid of them... That’s the one thing that people underestimate about civic associations: you don’t know how big they are, but you don’t want them mad at you.

The lack of widespread participation in neighborhood associations is one of their greatest weaknesses. At their worst, they claim to speak for the neighborhood but in truth are only five wealthy retirees in an institutional trench coat. Associations’ statements are sometimes given undue weight in the proceedings of local government because they appear more representative than they actually are. (No need to talk to all the residents: Just ask the association what the “community” thinks.) Said Melissa of FOKP:

If people want to talk to the “community,” that’s kind of a difficult thing. FOKP wants to represent the community, but not everyone gets engaged… There are plenty of people who don’t come to meetings, and their opinions matter too.

Associations can also be actively exclusionary, as was the case in early 20th century D.C. citizens associations, which helped keep the city racially segregated for years. With the power of speaking for the neighborhood comes the responsibility of building a membership that’s as representative as possible.

When Covid hit, neighborhood groups wondered if they would be able to continue carrying out their functions. Though they aren’t known for their tech savvy, they were forced to adapt, reinvent themselves, and temporarily virtualize their operations. The pandemic brought the traditional role of associations into stark relief and made it easier to see what’s unique about their niche in the governance landscape. (Sometimes it’s hard to know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone). What did associations experience when they clicked “Join Meeting” and jacked into the cloud neighborhood? What can we learn from this forced digitization of the hyperlocal?

Part 2

Zooming in: How Civic Associations Adapted to Wholesale Virtualization

“Organizations like ours really struggle because there’s not an easy template to switch online,” said Jenny Prime, a lawyer and president of the U Street Neighborhood Association in Washington D.C. There aren’t many local governance participants who are trained in digital community management.

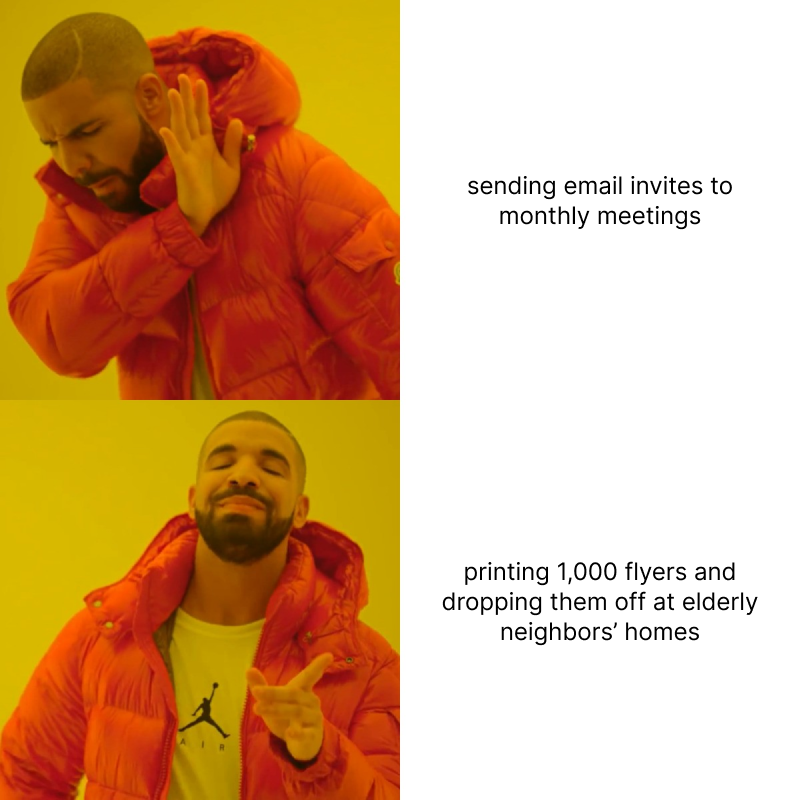

Jimmel Sanders agreed. “The backbone of the neighborhood is of course our seniors; how do we get the information to them in terms of the login to Zoom and audio? . . . They want to deal in paper.” Associations had to go out of their way to make sure that their newly online meetings were accessible to residents. Some of them divvied up the neighborhood, assigned block captains, and distributed hundreds of flyers to doorsteps. (Associations don’t have the luxury of assuming that their boundaries are coterminous with the internet.)

Once these initial logistical difficulties were ironed out, Zoom was a “savior . . . in many ways,” said William Emmet. Most everyone we spoke with said that digitization made local governance easier to participate in. Associations, in many cases, saw increased attendance at their membership meetings because they were suddenly just a click away.

To Paula Meuller, Executive Chair of the Queen Anne Community Council in Seattle, the pandemic brought about a dyadic shift on the local level, encouraging greater participation:

Because people were, you know, at home more, I think the pandemic caused people to … learn who your neighbors were. And so it seemed like there was more of a willingness to respond to surveys and to interact. And we now have more people who attend meetings.

In Washington D.C., Tricia Duncan concurred: “[Members] can eat dinner, drink wine, do something else; they can have it on in the background.” This had profound implications along gendered and classed lines: opening the doors of local governance to parents with small children and others who would not have the excess time or energy to participate. Zoom meetings also improved accessibility for immunocompromised people and people with disabilities. And, on the governmental side, associations had an easier time attracting guest speakers from municipal agencies, because officials could attend, give updates, and answer questions from home. We found plenty of recorded Zoom meetings and educational content (with ~17 views) on the YouTube channels of these hyperlocal groups.

Many associations found that they were far more pragmatic and efficient in cyberspace. Eric Langenbacher, a political science professor at Georgetown University and the president of Burleith Citizens Association in Washington D.C., said of Zoom:

There are certain things that I almost prefer doing via Zoom versus in person. Something about being in person, our board meetings will just drone on for ours. With Zoom, we’re done in an hour and a half and we get through everything.

(Adam, our token French researcher, did deep apartment cleans during Zoom church board meetings. Things have been dustier since resigning.)

Associations fared well without high-tech decision-making or polling software. In the spirit of Bob’s Rules, they cast votes using Zoom’s “Raise Hand” feature in calls packed with 100+ members. They eyeballed the results, only making an official count when things looked neck-and-neck. For D.C.’s Palisades Community Association (PCA), Google Forms was good enough for making high stakes decisions about land use in their neighborhood, which borders George Washington University. PCA used a survey, distributed via email, to solicit feedback on campus expansion plans.

Now that local orgs are more practiced at bringing their members together online, some of our interlocutors also hinted at the nascent formation of a city-wide network of associations (an other internet), in part because digitization makes organizing an inter-neighborhood mega-meeting way easier. David Kaplan of the Magnolia Community Council in Seattle, for example, cited the ease of not having to find parking as a reason for greater inter-neighborhood liaising. At once a condemnation of our poorly built public environment as well as a new means for sharing ideas, best practices, and policy goals with one another, the growth of these particular virtual meetings can undo groups’ isolation from each other.

But the limitations of digital gatherings became more apparent as the pandemic dragged on. Virtualization made participation easier, but it also changed what participation means. Stan Benton of Penn Branch Community Association was initially surprised by how many people showed up to digital meetings, but the quality of engagement left him feeling frustrated. Many of our interviewees worried that these newly “remote neighborhoods” were turning their formerly active participants into spectators of Zoom. “It’s tough. When it’s not an exciting meeting, a lot of cameras turn off, so it’s just me speaking into a black hole,” he said.

Pamela Wessling of D.C.’s Logan Circle Community Association (and many others) noted that the 2-dimensionality of digital means it’s not easy to create those all-important liminal spaces before and after gatherings. “It’s a lot harder to reach people on Zoom, personal connection is tougher to establish. There’s not the chitchat before meetings or when people walk home together.”

The informal, interstitial zones where much of the “real work” used to happen have disappeared: IRL social events, the bread and butter of these communities, were canceled entirely. Without the barbecues, potlucks, Octoberfests, and field games, associations begin to get swallowed by the machine logic of the tools they were uploaded into. As John Capozzi of D.C.’s Hillcrest Neighborhood Association points out:

It’s harder to remember people over the computer. There’s context to where you meet them in person… this is where Zoom causes a bit of trouble. It’s a different level of commitment. It’s easy to show up over Zoom and not really feel like you’ve made a connection with the other person.

The Zoomification of local governance has made it easy to be highly functional without being social; it has unbunded the administrative from the communal. When the round table becomes a grid of rectangles, it’s difficult to form the 1:1 relationships that make participating worthwhile. (Remember, the work of maintaining a neighborhood association is often unsexy and almost always unpaid.) What makes associations an interesting social technology in the first place is their ability to function as an alternative to the “consumerist model of city-citizen relations” (Shkabatur 2011). They link neighbors together in a “holding body” that, when paired with a physical community meeting space, affords more possibility than is available to unassociated web2 users. All this is not to say that associations should avoid using the latest and greatest communications tech, or that they shouldn’t offer digital participation options for members who can’t meet face-to-face. It’s about ensuring that this tech is wielded in service of the IRL neighborhood, not its digital twin in the cloud. Fully virtual associations risk retaining their bylaws but losing their heart.

Conclusion

As pandemic restrictions begin to loosen, the virtualization of local governance becomes, like almost every other pocket of atomized life, less a requirement and more a choice among a suite of imperfect options. The decisions, habits, and precedents made now will likely stick around for a long time to come. With fewer top-down mandates comes an opportunity for each of us to think critically and intentionally about how we gather.

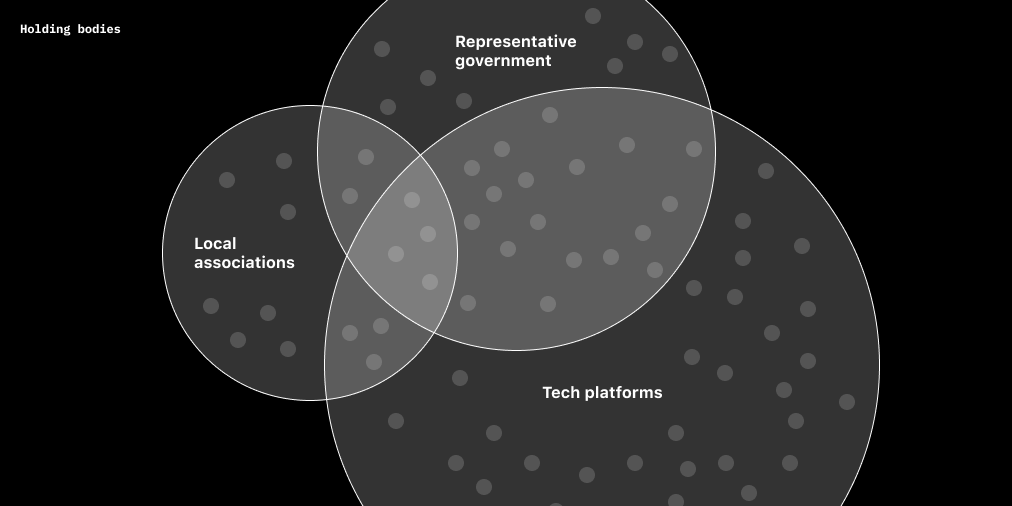

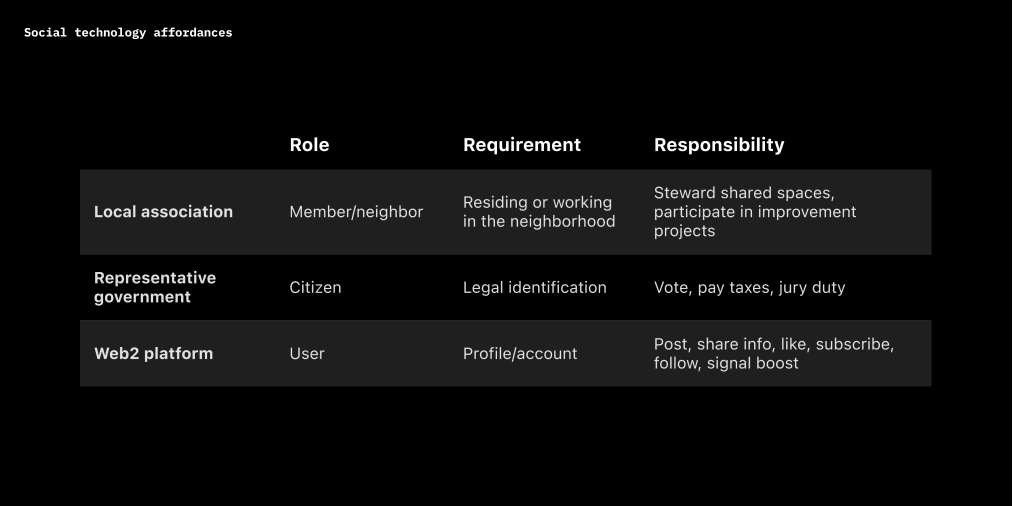

Neighborhood associations, web2 platforms, and municipal government in some ways compete to be the most representative layer of the governance stack. Not everybody participates in local associations, not everybody is on social media, not everybody votes or talks with their representatives. Though these three layers interpenetrate in interesting ways, they each have their own method of aggregating people, facilitating communication, and practicing the “art of association.” They each come with their own affordances and cast us in a particular role, which in turn shapes our sense of what’s possible.

The role of “citizen” implies a vertical relationship between you and your elected officials (it’s a legal status bestowed or denied by the state). Your job is to vote, pay taxes, and attend jury duty. The role of “user” implies an extractive relationship between the client and the service provider (it’s bestowed by tech platforms). Your job is to post, share information, like, subscribe, follow. The role of “member” in an association implies a horizontal relationship between individuals in a geographic locale (it’s bestowed by your residence or work in the neighborhood). Your job is to live peaceably with the people next door, steward the spaces you share, and participate in improvement projects. We can of course be multiple or all of these roles at once, but the context from which we draw our primary sense of civic identity has a huge influence on how and what we build. First we shape our social technologies, and thereafter our social technologies shape us.

Our research has shown that associations are unique in their ability to facilitate relationships among neighbors who would’ve otherwise remained strangers, and help them cultivate collective agency in the local governance landscape. They are themselves an underutilized social technology—one of the few vessels that remain somewhat outside the constraining logics of platform monopolies, markets, and the state. And unlike the holding containers created by web2 platforms, where citizens often feel they’re shouting into a global void, associations provide genuine pathways to local levers of power.

It would be easy enough to overlook geographically bound associations: to slowly forget what these open-ended local orgs are even for, now that we can rely on FB Groups, Twitter, Nextdoor, and, increasingly, Discord servers and DAOs, to connect us together. But associations are in a position to supplement the ethereal everywhere-all-at-onceness of digital media with local conviviality and neighborly initiatives. When membership takes precedence over usership, we expand—to harken back to Tocqueville’s excerpt—our freedom to collectively shape the built environments we call home.

Works cited

Chaskin, Robert J., and David Micah Greenberg. "Between public and private action: Neighborhood organizations and local governance." Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44.2 (2015): 248-267.

de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America: And two essays on America. Penguin UK, 2003.

Shkabatur, Jennifer. "Cities at crossroads: Digital technology and local democracy in America." Brook. L. Rev. 76 (2010): 1413.

Tufekci, Zeynep. "Twitter and tear gas." Twitter and Tear Gas. Yale University Press, 2017.

©2024 Other Internet Research Institute