Introduction: What Is a Brand?

A brand is the complete set of concepts, expectations, impressions, and reputations that are associated with a given entity. Usually that entity is a company or product. A product can mean different things to different people, and this difference can be especially strong when comparing the visions of people who run a brand to the perceptions of its customers. WeWork did not set out to have a "bad" brand.

A brand is not the product itself, but it is strongly determined by product characteristics and deployment. When people come in contact with a product, they form impressions about the brand based on direct experience. Products have affordances which give users impressions and suggest to marketers possible brand positionings.

A brand also isn't the "visual identity," but is often strongly determined by graphic cues from brand assets, product design, advertisement, etc.

So, if a brand isn't the product, the copywriting, the mission statement, the founder's vision, the designer's aesthetics, or the employees' actions, what is it? A brand is a cultural phenomenon that emerges only when these things come into contact with people. A brand lives in the minds of those who are aware of it.

As a brand grows, it becomes more than a set of first impressions and associations. Its reputation precedes it. As impressions are shared across users and consumers, they often develop similar sentiments. In this way, a brand operates as a consensus system, facilitating a consistent set of beliefs across people.

Centralized Brands, Centralized Narratives

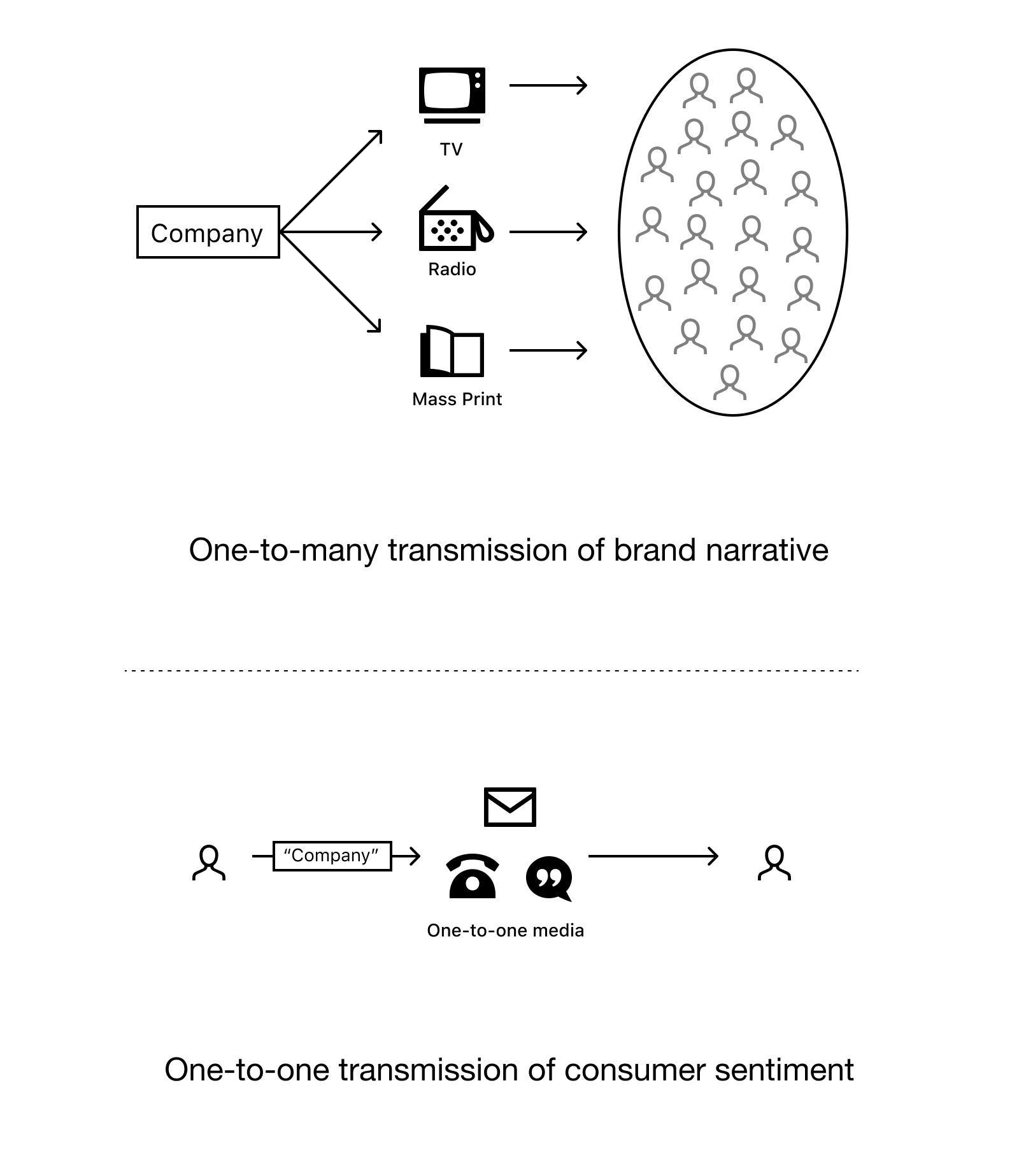

Traditional broadcast media offered corporations a high degree of control over audience exposure. Customers received consistent messaging about brands directly through advertisements in print, radio, and television media. However, the person-to-person transmission of this information **was limited by the communications infrastructure available to consumers at the time—predominantly spoken word, mail, or telephone. As a result, information aggregators such as Zagat, Consumer Reports, and Kelly Blue Book found opportunities to position themselves as important mediators of credibility in the pre-internet age.

Icons by Thomas Helbig from the Noun Project

Icons by Thomas Helbig from the Noun Project

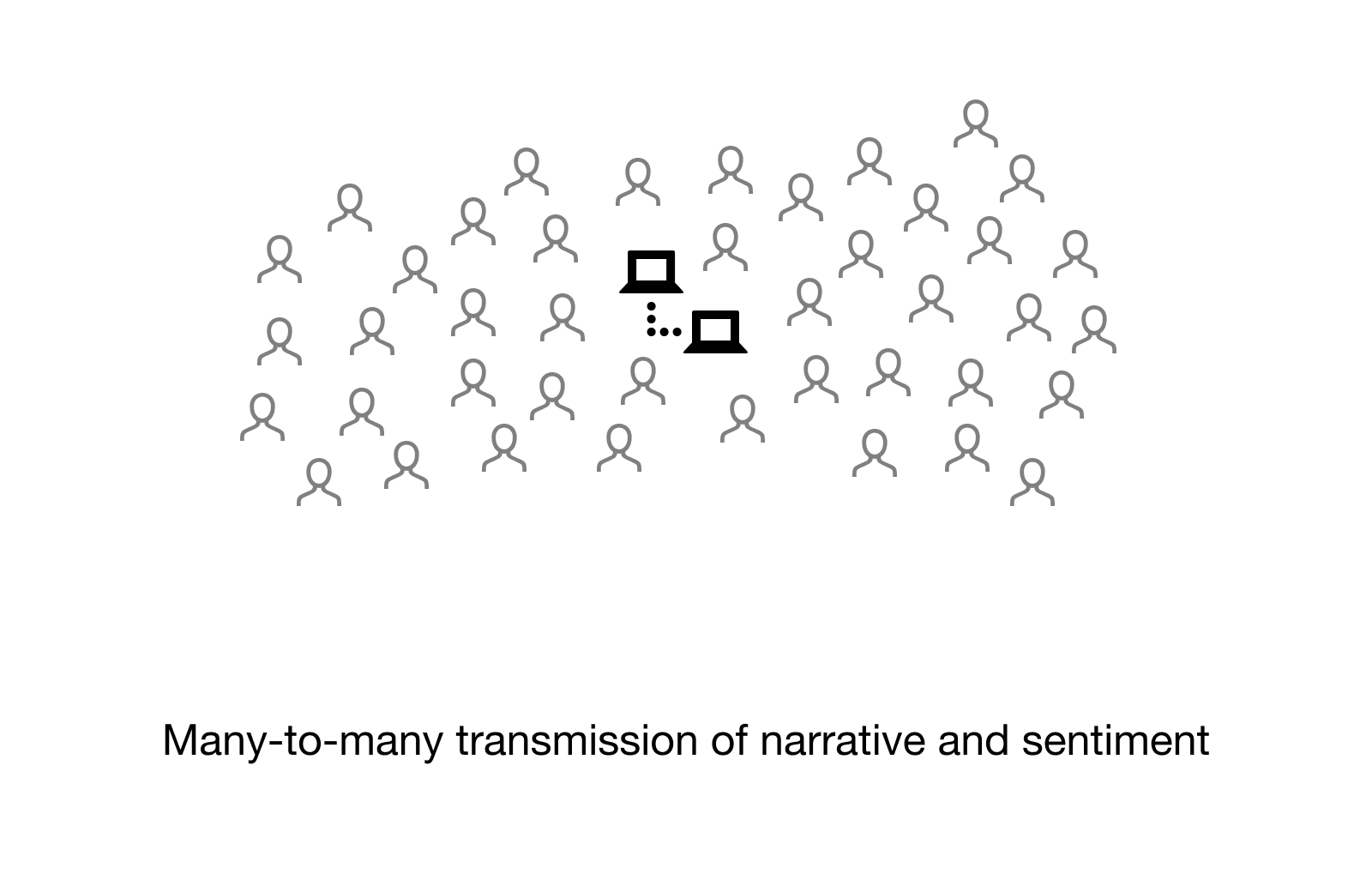

Since the transition from broadcast to networked media, brands have become significantly more volatile. The internet dramatically reduced the barriers to publish, while enabling anyone to access published materials, which allowed any user to make their opinion known to any other. User ratings sites like Yelp made traditional information aggregators less relevant, and introduced new channels for users to achieve consensus on a company's brand. Today the sphere of public opinion, including user review sites, personal blogs, and social media threads, constitute a new part of a brand. They are the "surface" of the brand's invisible body, against which official brand messaging can be compared and validated.

Because brands are constrained by the number of people who come in contact with them, they are directly affected by the accessibility and velocity of information. Overall consumer sentiment is now highly visible, so positive and negative brand sentiments can escalate and circulate throughout the network rapidly.

Most small companies have a position (often CEO, CMO, or VP of Marketing), who is nominally in charge of tending to the brand, i.e. managing the impressions and expectations that people have about the product. However, with the emergence of the social web, important signals shifted from a small number of review sites to an abundance of real-time social media streams, challenging marketing teams with the Sisyphean task of satisfying the whims of an endless feed.

In response, many companies have hired social media managers who use either reactive or proactive brand management strategies to keep the brand image in check.

Reactive strategies seek to keep the brand aligned with current events and manage user feedback dynamically in real-time, whereas proactive strategies aim to produce content that will disseminate broadly within the network, or induce customers who identify strongly with the brand to act on the brand's behalf. This latter behavior, often termed "values-based branding" or "influencer marketing," relies on users to organically promote brand awareness, and even defend a brand against negative feedback. Brand management of this sort attempts to steer the global narrative using strategies native to the current network model.

Despite widespread deployment of these methods, managing reputation and controlling brand narrative requires substantial company resources and is a significant vector of market risk. The fundamental tension of narrative control in the networked era is that most companies impose a hierarchical brand management model onto what has effectively become a distributed, permissionless process. And when the emergent meme-space of networked media meets censorship-resistant infrastructures, brands take on a life of their own.

Headless Brands

The discussion so far has been limited to centralized corporate entities that actively try to manage their brand presence. Corporations which own the majority of their own shares, and which centralize workers (production) and governance (strategic direction), can claim the right to to centrally manage their visual identity, messaging, and other "brand assets." For such corporations, influencer marketing might thus be viewed as a concession of narrative control.

But we would like to put forward an alternative view. We view influencer marketing as an early example of a larger shift away from the centralized model of brand management altogether.

Who or what can claim authority to manage a brand when ownership of a protocol is distributed among a network of users? In particular, who has the authority when those same users are often also responsible for the productive work of the project? When users own equity and stand to gain from increased adoption, those same users are strongly incentivized to spread awareness and hype about the project. However, because these "brand advocates" have no central management body or venue for coordination, there is no guarantee a strong singular narrative will emerge around the product or service.

Web 1.0 and 2.0 network technologies eliminated the marginal cost to distribute an idea and pushed the power to narrative formation out to the network, leading to both the chaos of real-time social media brand dynamics and the cohering force of influencer marketing. Likewise, emerging models of ownership and contribution in Web 3 pose a threat to brand cohesion, while also presenting an opportunity for community alignment.

We'll take Bitcoin as an example.

Bitcoin, the first headless brand

Bitcoin is the progenitor of all modern cryptocurrency projects and is by far the most recognizable brand in the space. Many people who have never encountered Ethereum, P2P, or blockchain, know Bitcoin.

Bitcoin has many strong brand characteristics, including a phenomenal origin story. Yet there is no person or entity responsible for maintaining this story. Bitcoin is what we're terming a headless brand. While Bitcoin was named and given a visual identity by a single visionary founder, Satoshi Nakamoto chose to remain pseudonymous, and has now completely disappeared from the public. All subsequent brand collateral—visual assets, messaging and positioning, and more—have been created by groups of community stakeholders. This has become the driving dynamic of Bitcoin's evolution as a brand.

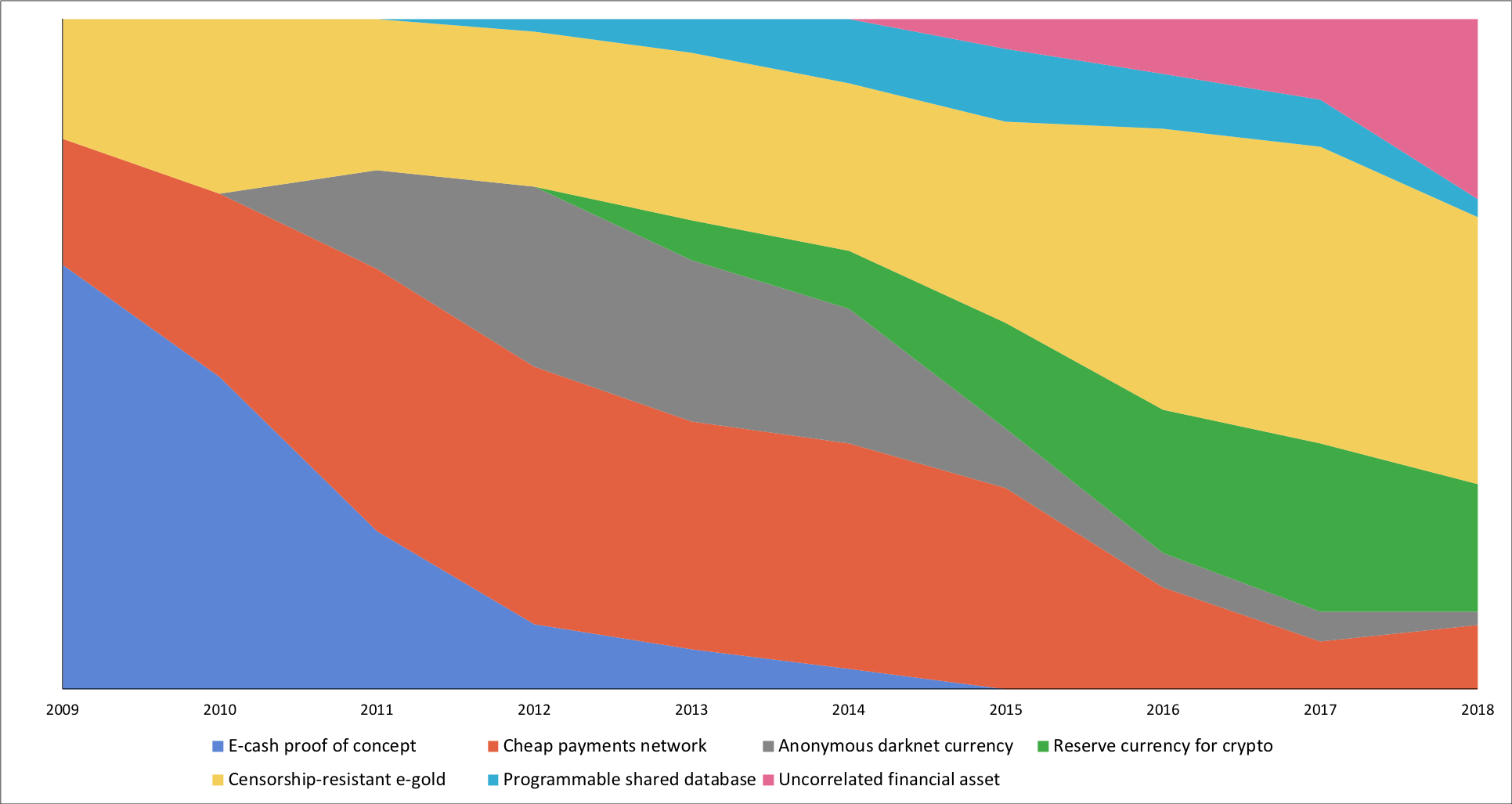

While Bitcoin's core contributors have had an influence on the Bitcoin narrative, there are millions of other stakeholders, many of whom have meaningfully contributed to its brand. Nic Carter's Visions of Bitcoin piece captures the evolution of Bitcoin's emergent brand proposition: from electronic cash, to censorship-resistant store of value, to uncorrelated financial asset. These narratives often conflict with one another, but each contributes to Bitcoin's overall brand presence. Alternatively, we might say that there are many different Bitcoin brands, which collectively contribute to its broader brand awareness. Importantly, each of these narratives has driven new market dynamics and new buyer segments.

Relatedly, the Bitcoin ecosystem can be divided into several ideological camps. The Bitcoin software was initially distributed via the cypherpunk mailing list and this original group of cryptoanarchists form one such segment. And while technical enthusiasm spilled over into the CPU overclocking community, Bitcoin also broadly resonated with disaffected political factions formed in the wake of the financial crisis, from the Tea Party to Occupy. Darknet markets would prove to be the breakout use-case, bringing a wave of users primed by the dissident logic of P2P file-sharing who sought a way to circumvent illicit drug regulations.

Since then, many libertarians, bolstered by a resurgent interest in Austrian economics, have joined the ranks of "Bitcoin maximalists," a group characterized by their unwavering belief in the monetary supremacy of Bitcoin. Maximalists constitute the so-called "HODLers of last resort" whose refusal to sell creates Bitcoin's price floor. Maximalism has itself led to bizarre forms of ideological extremism, exemplified by "Bitcoin carnivores" who stretch the libertarian ideals to their dietary regimen, declaring themselves both against fiat money and against "fiat food."

While in many ways politically divergent, what unites these maximalist groups is a shared goal of bringing about a hyperbitcoinization event, the possibility of supplanting fiat currency with a single non-state alternative: Bitcoin.

A final but crucial pillar of Bitcoin's brand is its protocol characteristics. Many of Nakamoto's early design decisions have become recognizable elements of Bitcoin's brand presence.

- "Hard money" — the 21M fixed supply and resulting deflationary economics has been a major driver of adoption.

- Non-fiat money — its status as a non-state money allows for Bitcoin to frequently be folded into anti-authoritarian, economic crisis, and collapse narratives.

- "Proof-of-work" — the novel consensus mechanism introduced by Nakamoto solved one of cryptography's hardest problems; more recently, the term has entered into the culture as an evocative analogy for any validation mechanism that relies on expenditure of energy and resources.

- Whitepaper — Bitcoin's release format is one of its most iconic elements, spawning thousands of imitators.

- "Block chain" — a throwaway phrase mentioned once in the whitepaper as "chain of blocks," which took on a life of its own.

In the absence of structured brand management, these design decisions have become well-known tenets of Bitcoin's brand. The immutability of these core protocol mechanisms has allowed for many narratives to emerge on top. The Bitcoin Cash fork is perhaps the exception that proves the rule.

When Bitcoin Cash forked, OG Bitcoiners were able to express their belief in the new brand by adopting the equivalent amount of their balances in the forked chain. The fact that many did not opt to take custody, or simply dumped BCH on exchanges, is telling of the profound brand divergences between these two visions. While BTC has strengthened since the fork (Crypto Winter notwithstanding), BCH has undergone further forks, pointing to the fact that the Bitcoin Cash brand has also continued to evolve, albeit in a tortured manner.

In summary, Bitcoin's shifting brand results from three main characteristics: 1) Bitcoin is headless, completely lacking a centralized entity which attempts to control its brand presence; 2) its defining protocol design decisions are immutable; 3) its users are financial stakeholders and workers in the network, both of whom stand to gain from increasing adoption of the Bitcoin protocol. Users' financial stake in the protocol has created incentives to spread their own version of the Bitcoin narrative. If brands are a consensus system, Bitcoin constitutes multiple narratives which converge on a single Schelling point: the dominant BTC chain.

Exit vs Voice and Headless Governance

The Bitcoin hard fork was first and foremost a narrative divergence starting from two different visions for the blockchain and ultimately resulting in two different Bitcoin brands—BTC and BCH.

Headless brands, especially those without formal governance structures, are at risk of such narrative forks. This leads to another set of questions: to what extent do we want to mitigate forks, rather than letting visions, narratives, and aesthetics diverge and evolve on their own terms?

Contentious hard forks result from a narrative split within the existing set of stakeholders. However, while these discrepancies risk jeopardizing the consistency of the original brand, allowing the exit of dissenting parties may help consolidate narratives and, in turn, attract new adepts, avoiding the dangers of internal cannibalization. The main Bitcoin community, for instance, benefited from clear resolution on block size as dissenters cleanly expatriated to the BCH fork.

Layer-1 projects with on-chain governance, such as Decred, Tezos, and Amoveo (and soon-to-be launched projects such as Polkadot and Dfinity) offer a different set of strategies for dealing with a narrative fork. They do this by internalizing the option to exit and reformulating it as a stronger form of voice, not unlike the unifying effect of universal suffrage in modern constitutional democracies.

Decred and Tezos, for instance, ratify support for backwards-incompatible changes with on-chain voting by token holders. Amoveo creates a path to legitimacy by adopting the "fork-futures" model, originally proposed by Paul Sztorc preceding the BCH fork, in which a prediction market outcome is used to resolve divergent protocol rulesets. These strategies give their respective communities a new path to form meta-consensus, for better or worse.

While such designs cannot prevent users who do not recognize themselves within the main narrative from exiting the system altogether, these projects are able to change the dynamics of community cohesion and coordination around the brand narrative by providing an additional in-protocol path to resolution. Protocol design choices, and specifically governance models, directly impact a headless brand’s coherence.

Headless Brand Development

Headlessness is a new model for products and services brands made exclusively possible because of distributed cryptonetworks. Decentralized branding is facilitated by users truly empowered to create their own narrative, and incentivized to spread it.

However, the mere existence of a blockchain does not ensure a successful headless brand strategy. So how do decentralized systems with permissionless brands maintain coherence? Is there a right time for a Web 3 organization to "go headless"? And how do protocols and products discover the right audience segments in order to find adoption? In this section, we discuss the ingredients of a successful headless brand during consecutive phases of development.

Pseudonymous Founders

Bitcoin has unique brand cachet as the first viable cryptocurrency, but other organizations have also recognized the value of concealing the project's origins. Monero's whitepaper, for instance, was also published under a pseudonym, "Nicolas Van Saberhagen," and the codebase was initiated by a group of pseudonymous developers. Newer initiatives such as Grin and Fomo3D have also taken advantage of pseudonymity in order to decentralize development, sidestep regulatory concerns, and imbue their origin story with a degree of cypherpunk mystique. Grin is particularly noteworthy in this regard, starting with the pseudonymous Mimblewimble whitepaper dropped as a .txt file in the #bitcoin-wizards IRC channel. Several members of the core development team, including the founder of the project, "Ignotus Peverell," still maintain pseudonymous identities. Grin's headlessness is supported with other strong brand decisions. The affordances of its rebellious, cheeky logo—such as pasting it over faces in photos—make it extremely memeworthy and suitable for altcoin hype.

Personalities As Single Points of Failure

"Bus factor" is a typical metric for evaluating a system's degree of organizational decentralization. We can estimate this value for a given brand by asking: how much can the brand be harmed if a core team member or identifiable founding figure were to die—or in 2019, be canceled?

Ethereum is an instructive example in which the project's brand is largely associated with its founder. Vitalik is probably the only individual in the Ethereum ecosystem with the capability of personally altering its brand identity. However, the Ethereum team has also made design choices which show an effort to "keep the identity small," such as their endorsement of related projects using altered versions of the Ethereum logo. Additionally, the ongoing debate about the nature of ETH (is it a world computer? is it money? is it "lego blocks" for money?) testifies to the headless evolution of Ethereum’s brand. Vitalik has yet to pronounce himself on the "ETH is money" matter, but the liveliness of the community, coupled with the strength of the #DeFi brand, are evidence of a decrease in Ethereum's dependence on its founding figure.

In contrast, TRON—a project born as a clone of Ethereum (from the plagiarized whitepaper down to the “TRC-20” smart contract standard)—heavily revolves around CEO Justin Sun’s cult of personality. Notably, when Sun announced the postponement of his highly anticipated dinner with Warren Buffet due to health issues, the TRON token price dropped 13.5% within 12 hours. This points to the implicit risk of centralizing a brand around a founder’s persona: an identifiable founder can be a single point of failure in any Web 3 brand strategy, affecting market dynamics in sudden and unforeseeable ways.

The Whitepaper

The whitepaper trend began as a reprise of Bitcoin's release format, but has since become something of a tradition for the blockchain industry. For headless entities in particular, the whitepaper plays key role in setting the tone and narrative direction for the project's continued development.

As in constitutional law, we see a tension between textualist and intentionalist approaches to interpretation of various founding artifacts. This applies to the whitepaper, as well as technical drafts and correspondence that contribute to the founding mythology. What did Satoshi really mean by "peer-to-peer cash"? How was Vitalik using the term "smart contract"? Deriving meaning solely from the text as-written, or viewing these artifacts through the lens of intentionality, may result in wildly differing interperative results.

Like scripture, repeated reinterpretation in pursuit of deeper meaning or a founder's true intentions persists under circumstances of incomplete information and the personal significance of filling in consequential gaps. Because the design of a cryptocurrency directly impacts issuance and distribution, alternative readings of a single passage (for instance, acceptance or rejection of ASICs) can lead to considerably different allocations of wealth.

Thus, even in projects where the founder is anonymous or has completely severed ties, the headless dynamic that fills this absence is never truly anarchic. Active followers find a way to walk forward the headless body of a project's founder.

Brand Differentiation in Products vs Procotols

While product brands typically have a clear focus, should protocols pursue the same strategy? Layer 1 protocols aiming for ubiquity may have less success with highly differentiated aesthetics than intentional application of genericism. IPFS, Bitcoin, and W3C standards are projects that aim for a sense of opinionated generality in their design and messaging. Such gestures toward minimalism and universality are not unlike the design language taken up by global infrastructure companies like IBM, Oracle, and AWS.

Yet a generic brand strategy seems to conflict with many efforts in the broader decentralized web to build a vertically integrated solution spanning multiple layers of the stack. Confusion can arise if a product shares branded elements with an underlying protocol, as the highly-targeted messaging and aesthetic differentiation of product branding pollutes lower level protocols.

One way some projects pursue ecosystem-building while sidestepping this challenge is by spinning out team members to work on Layer 2 and 3 projects under new brands. The 2018 move of Blockstack co-founder Ryan Shea and another founding engineer to independent organizations building on the Blockstack network is one high profile attempt at such a strategy.

Finding Market-Product Fit

Traditional startup brands are, in the immortal words of Clayton Christensen, solving a job to be done. Especially in B2B markets, a startup brand often speaks to a targeted customer with specific problems and makes promises to alleviate them. For early-stage venture-funded Web 2.0 companies, a brand represents the following:

- a description of the "job to be done" and commitment to finding adjacent product-market fit

- a target customer and prospective market size

The role of the brand manager in this regime is to create an interface between the product and customer segments being explored. When the product ultimately connects with the right customers, the brand will also typically go through a reorganization, solidifying its "brand-market fit."

How do projects, headless or not, find product-market fit in the Web 3 era? Well, in some senses they don't. In a highly decentralized system, these operations invert such that the community finds product solutions themselves: "market-product fit." Cryptoeconomic protocols are market frameworks looking for potential product applications. The work of exploring parallel narratives, discovering emergent use cases, and testing solutions is distributed among members of the wider ecosystem such that the rising tide lifts all boats.

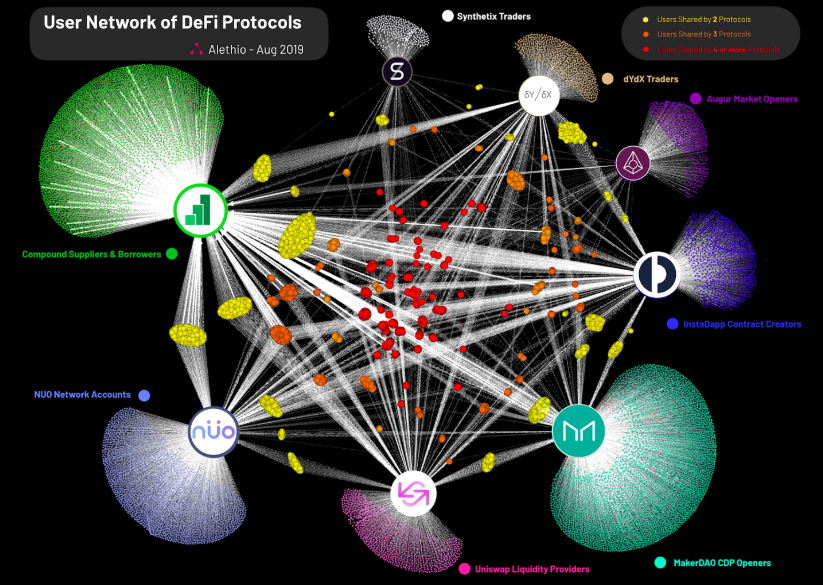

#DeFi exemplifies a class of use cases which have emerged within the Ethereum ecosystem. However, DeFi isn't a single coordinated entity, rather it's a family of new financial products made possible by the permissionless composability of Ethereum-based protocols (the most prominent of which are MakerDAO and Compound Finance, though the field is rapidly expanding). Similarly, DeFi is not a single narrative or aesthetic. Each project is free to tell its own story and define its own use cases, but together they converge under the #DeFi banner to reinforce the meme that Ethereum is "programmable money." The recent news that Maker was denied trademark application for DEFI seems to further support this argument.

The discovery of #DeFi as a core use case is attributable to A) the development of token standards and B) the community of Ether holders and traders incentivized to find new cases to grow their wealth. It does not follow, however, that simply deploying a new currency or smart contract into an ecosystem guarantees the community will find a successful narrative or use case.

Source: Alethio DeFi series

Advanced Strategies for the Headless

Web 3 projects are open source by nature, which means that technology can not only transfer horizontally from one protocol to another, but the entire state history can fork as well. This begs the question: if projects no longer have an exclusive claim on technology or the underlying data, how can they maintain a competitive advantage?

Brand is one of the strongest assets for decentralized protocols. A headless brand strategy is an ecosystemic affair and entails the mobilization of a decentralized set of actors. At its core, it revolves around giving agency to different stakeholders in a way that lets them coordinate more effectively and feel connected to the brand. What projects can do, in this context, is provide the resources, tools, and wayfinding devices for different stakeholders to converge around a single narrative.

Below is our (incomplete and partial) list of recommendations for different actors in a headless brand’s ecosystem to facilitate and reinforce the social consensus around an emergent narrative.

| Protocol Developers Security Through their design choices, protocol developers play a key role in providing the initial conditions for a headless brand to emerge and evolve. The selection of cryptography and security model remains key to brand trust for secure peer-to-peer protocols and cryptonetworks. Any security vulnerability can directly undermine the brand built around it, exploited or not. Base chains which suffered successful 51% attacks, such as Ethereum Classic and Horizen, are still in the process of rebuilding their brands. Node Operator Experience While there is a general trend toward the professionalization of node operation, it may be beneficial for headless brands to boost consumer node operation, which may also help with network availability and decentralization. How could running a node be more of a compelling experience? How do I signal to my friends that I'm running a node? Can running a node feel like a game? Blockchain projects might learn from how older distributed computing projects like SETI@home, Genome@home, and Folding@home turned distributed computation for public purpose into a user-facing application. Clovers, a game in which users "mine" new arrangements of visual patterns as sort of "proof of work," points to how gamelike social layers can both enhance and legibilize crypto. While many hypothesize that users of future blockchain-based applications will "not even know it's on the blockchain," improving the mining, staking, and node-operating experience may be a fruitful line of innovation. Coin Ownership Experience If each token and protocol has its own brand, why should token ownership take the banal metaphor of a generic "wallet" with numbers? Could coins and cryptoassets bring their own interfaces to users' smartphones? Can coin ownership be turned into an aesthetic or a collective experience, in which the curation of one’s own cryptoassets portfolio can function as a signal to aligned token holders and projects, similarly to how people curate their Pinterest boards or Instagram feeds? Designing and implementing these experiences will hinge upon the development of infrastructural components often outside the purview of individual protocols (e.g. wallets, curation markets). Projects that are highly concerned with their own brand, and want to build network effects around the socially-shared sets of values of their users, may want to consider pursuing this strategy. Governance As illustrated above with the examples of Bitcoin, Tezos and Amoveo, the governance model of a protocol directly impacts a headless brand's strategy. Projects should make sure that their brand strategy reflects and is aligned with their protocol design choices. If in traditional media, a brand's strategy was absolutely constrained by the product characteristics, the headlessness of Web 3 brands is a direct function of the in-protocol affordances for voice and/or exit. |

|---|

| Open Source Community Following the idea of influencer marketing and "decentralized brand management," developers, contributors, and community personalities are a resource for advocacy and network effects. There are several levers that can contribute to strengthening the social layer on top of projects and generate new interest in the technology and associated brand. Brand Composability Projects gain additional social proof from the companies that build on top of them. New grassroots narratives such as #DeFi are already emerging from the possibilities of composability in the Ethereum ecosystem. Likewise, brand credibility can be bootstrapped by combining the brands of protocols on top of which new projects build! cDAI is effectively a new token brand, benefiting both Compound and DAI. Facilitating more of these "composed brands" is an opportunity for developers in a project ecosystem. Developer Experience Learning a new development stack is a significant personal investment and many developers have strong opinions and aesthetic preferences about their tools. Leveraging niche interest segments with a strong following and deep knowledge base, such as functional programming, or contributing to existing ecosystems (JS, Rust, WASM, etc), are playbooks from the Web 2.0 era that have increased relevance for the open-source communities around Web 3 projects. |

| VCs As early supporters of decentralized protocols, VC funds have an important role to play in the success of a headless brand strategy. In addition to providing liquidity and supporting prices in the open market, VCs can actively participate in a network through a generalized mining approach (involving staking, running nodes, curating, voting, etc.), using their own brand to attract talent to projects, as well as increasing ecosystem viability by funding composing projects, grants programs, and so on. Not only do VCs provide a key curation function for developers and other network participants, VCs also develop thesis that track broader narratives. Some of this due diligence is strategically disclosed, yet there may also be room to further open source the development, validation, and evolution of investment theses using information derived from deeper community engagement. |

| Token Holders Token holders themselves are vital project contributors. If they believe in a project, they can make themselves heard. They can make memes and blog posts, codify narratives and spread them. They can discuss use cases and give meaningful feedback to developers. They can shill your tokens and expose nocoiners. In a literal sense, the value of a token project is backed by the size and robustness of its community of believers. |

We will conclude with a few final remarks.

We are moving from an era of centralized, bureaucratic value creation firms to an era of decentralized, permissionless value creation networks. As organizational models change, so too will the intangible cultural artifacts created by these new institutional forms. Brands, narratives, memes—we now choose our own headless gods.

The very idea of a brand that is decentralized challenges our assumptions about what a brand is and how it operates. In 1971, famed brand manager Stephen King of J. Walter Thompson (now the world's largest marketing agency), described the first condition for a brand's success: "First, it has to be a coherent totality, not a lot of bits. The physical product, the pack and all the elements of communication - name, style, advertising, pricing, promotions, and so on - must be blended into a single brand personality." In 2019 it is unclear whether this axiom holds true, even for traditional products and services.

A decentralized brand is a meme. It belongs to no one, and can be remixed by anyone. A decentralized brand can only be "designed" in a very limited sense. It is something different than a Coca-Cola, an Uber, or a New York Times. Decentralized brands are self-enforcing, self-incentivized, contagious narratives that emerge and evolve in ways that are unexpected and irrepressible.

A decentralized brand is a fiction made real, an egregore, a self-sovereign entity that lives through the imagination and belief of many. One does not simply decide what a decentralized brand "is." It is not something that can be created by focus groups, strategists, and identity designers. Like Bitcoin, a decentralized brand has its own autonomy, generated by the contributions of individual actors, a million person chorus acting as one.

Thanks to Darren Kong and John Palmer for feedback and ideation.

Icons by Thomas Helbig from the Noun Project

©2024 Other Internet Research Institute