Proposal: Curating Value Exchange

As we discussed in a recent essay about public goods in the age of crypto, today blockchains are considered a public good in view of their open source and non-excludable nature. Yet this definition of “public goods” has done more to justify self-serving activities for cryptocurrency insiders than the term suggests. We wanted to counter this empty definition and advocate for a more expansive view, informed by historical and social notions of the “public” and “good.” The essay arrives at the idea of positive externalities: making the benefit of others axiomatic.

Instead of the destructive scaling effects familiar to web2, we wrote, “greater scale should mean greater good as valued by an increasingly wider set of people.” We see this as a design prompt for public institutions of all kinds: how can they achieve greater good as they scale?

We believe that our thinking on positive externalities can apply to a reframing of legacy public institutions, such as the Bundeskunsthalle. While the finances of public institutions are currently a matter of public record, few people who visit or interact with the museum care to access these resources. In certain disappointing but not unfrequent cases, this indirection can lead to the misuse of public funding to advance private political and business interests, as evidenced in the Bundeskunsthalle’s recent history. Crypto’s laundering of private interests as “public goods” poses much the same risk.

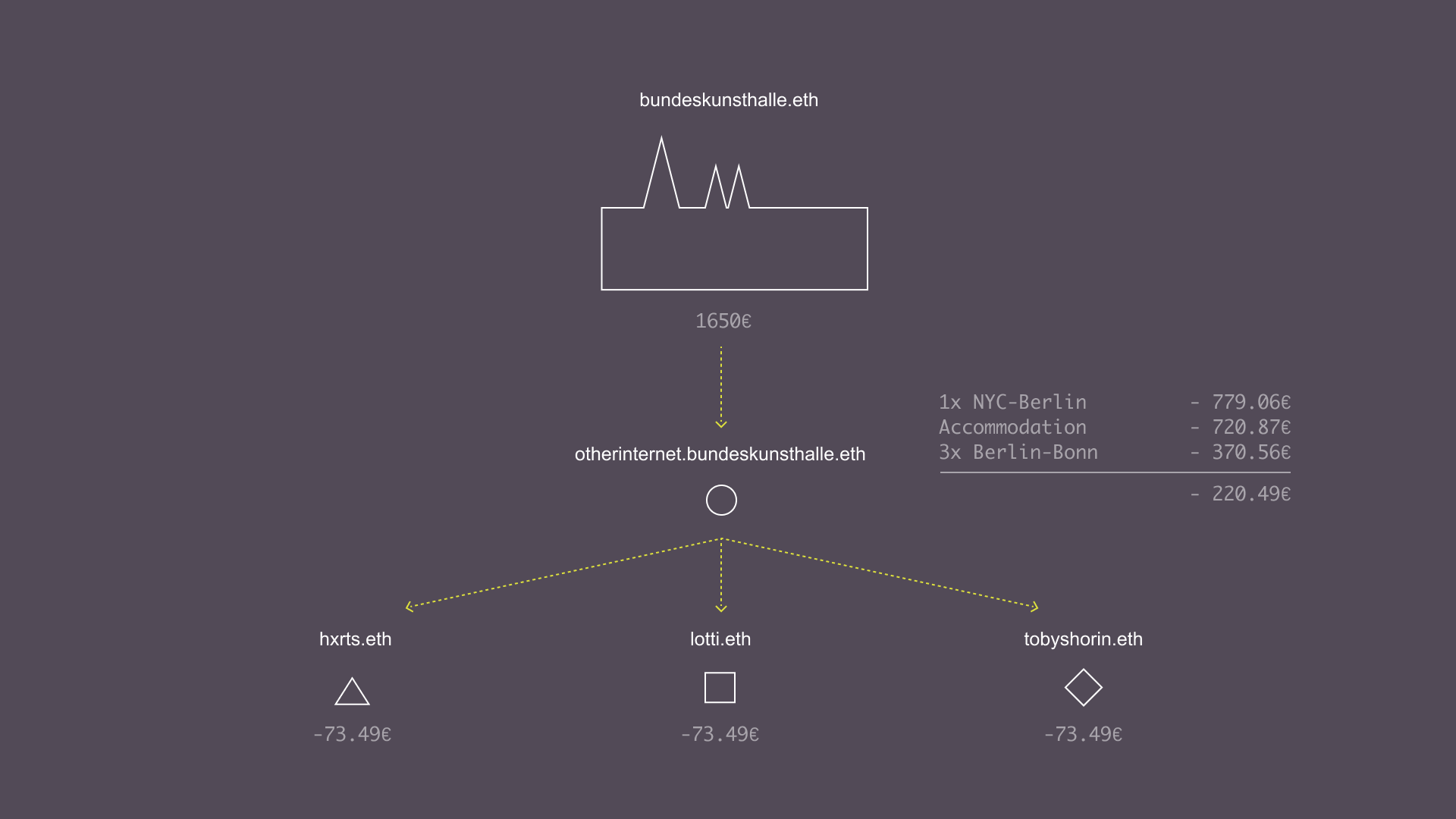

Our solution is to introduce a transparency device: using a public blockchain to make financial information accessible among a wider set of stakeholders, including artists, art audiences, art workers, and peer institutions. We propose using the squatted ENS domain, bundeskunsthalle.eth, as the basis for a public record of transactions related to a chosen exhibition. The Bundeskunsthalle could use the account to compensate artists and workers involved in the show in a transparent and publicly auditable manner, and then incorporate this financial ledger into curatorial materials such as exhibition catalogs or wall text.

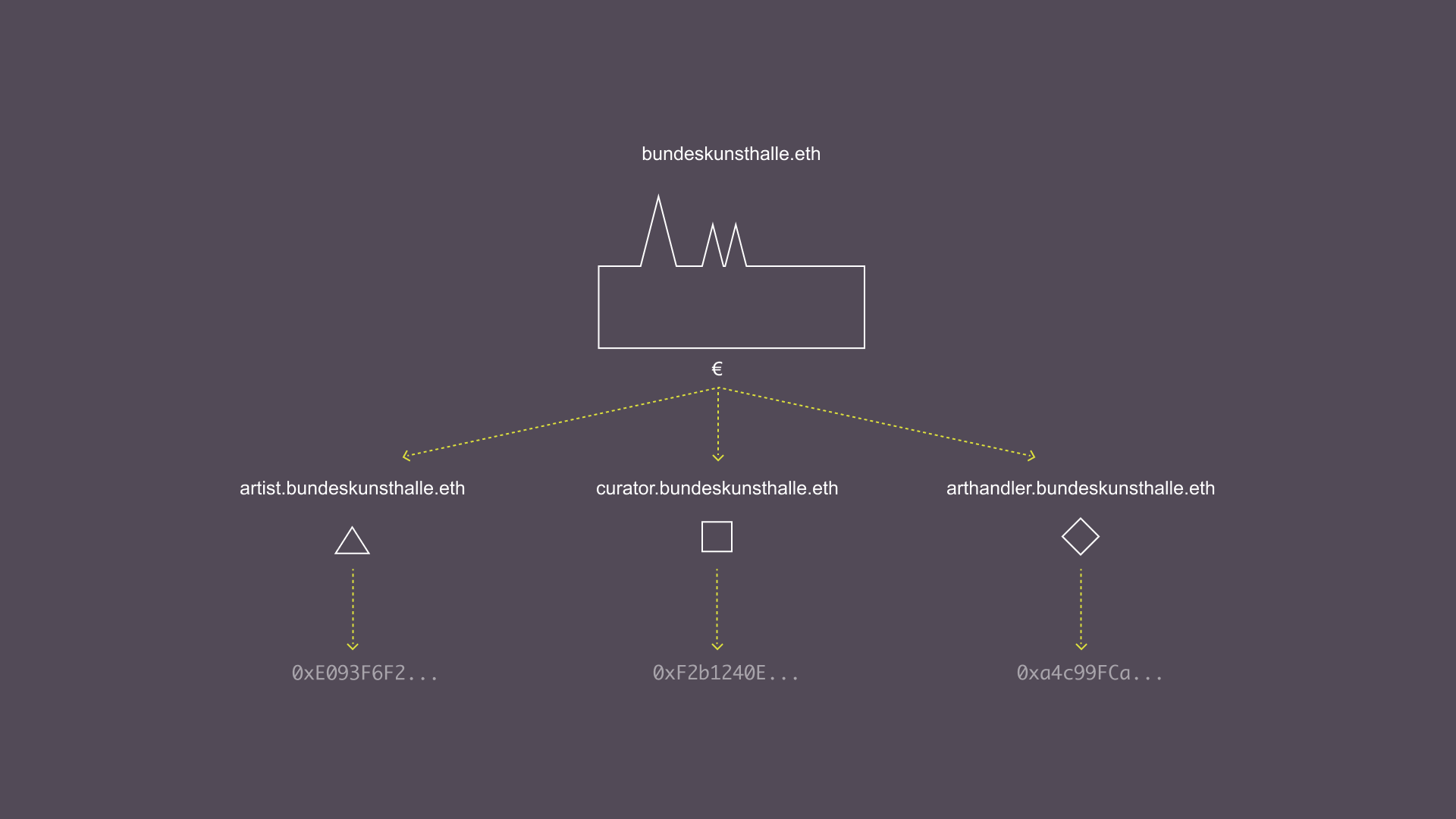

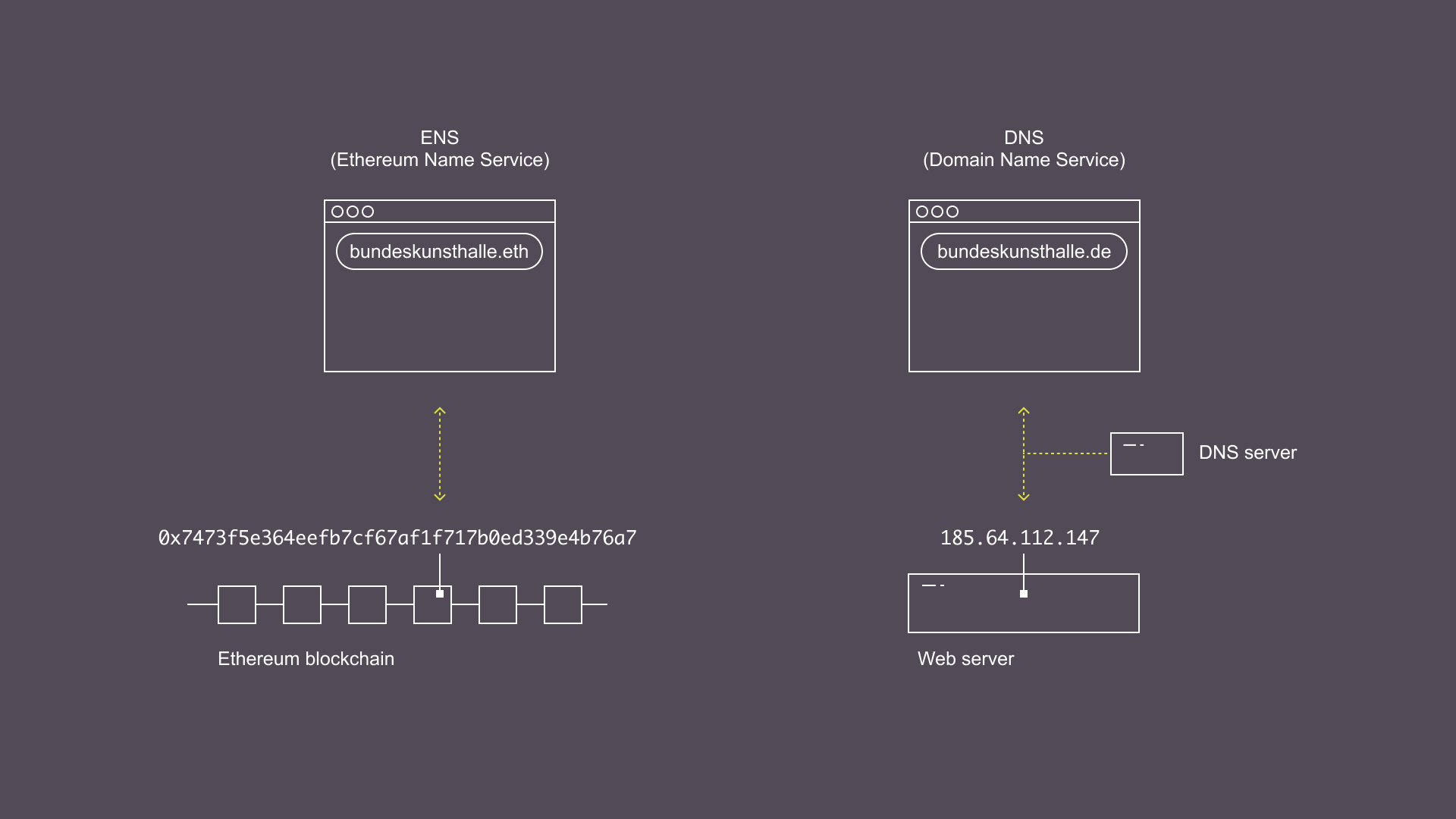

The Ethereum Name Service affords radical transparency, making it possible to assign public domain names to blockchain addresses held by specific transacting entities. ENS works much like DNS, the Domain Name System we use every day. DNS is “the phonebook of the Internet:” it translates domain names like bundeskunsthalle.de to numerical IP addresses corresponding to distinct machines, 185.64.112.147. With IP addresses, browsers can then locate and fetch Internet resources; with ENS, IP addresses are mapped to cryptographic addresses on the Ethereum blockchain. Internet phone numbers become bank accounts.

Notably, DNS addresses are also hierarchical, for example [tickets.bundeskunsthalle.de]. Here, each level of the name space [subdomain.domain.top-level-domain] is managed by the one above. Thus the ENS domain bundeskunsthalle.eth, held by the museum, could create and manage subdomains, pointing them to payable addresses in the control of independent parties.

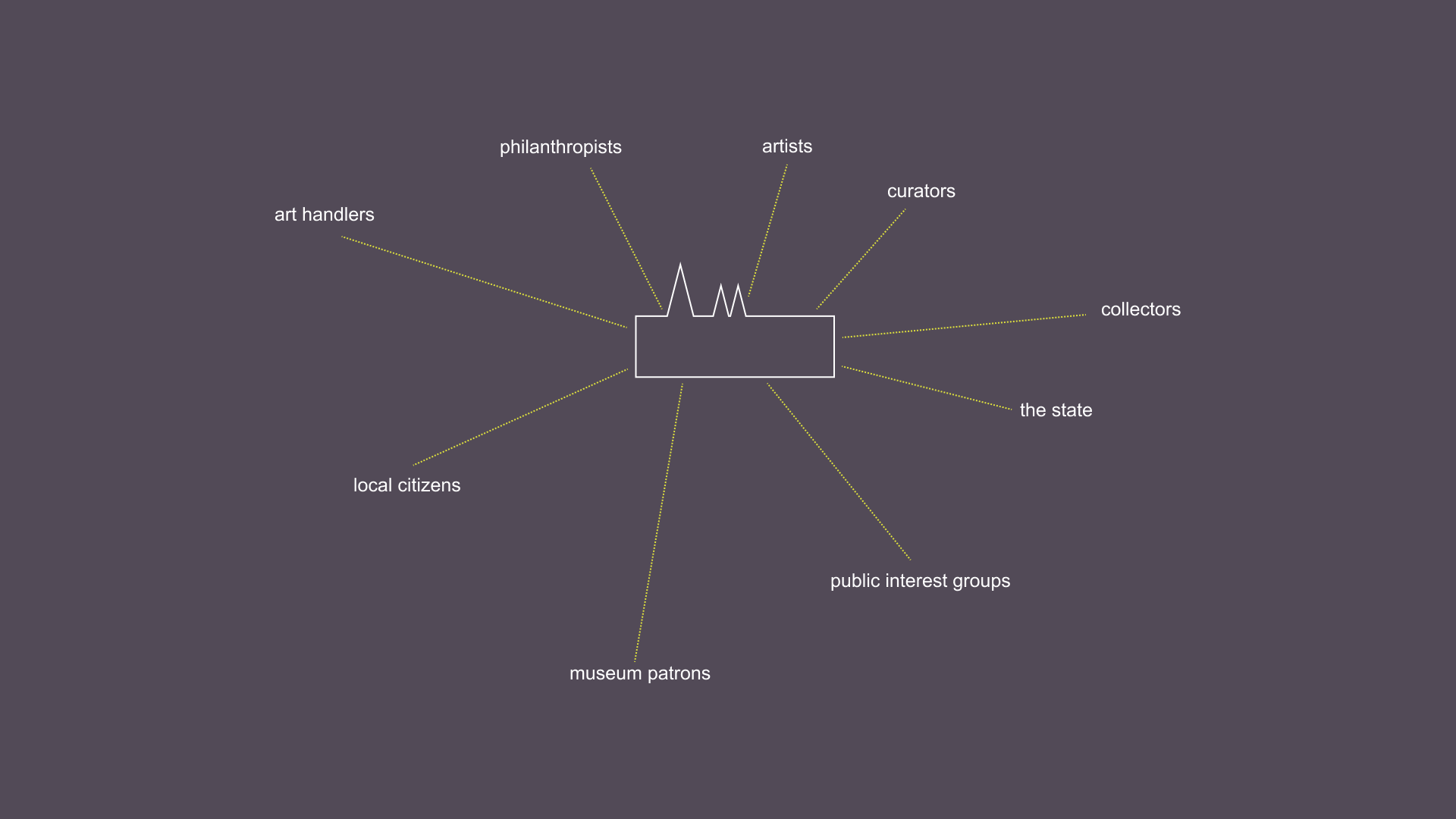

For instance, the Bundeskunsthalle could designate a given artist, curator, and art handler as significant actors in the example exhibition’s financials, as seen above. In this case funds sent to artist.bundeskunsthalle.eth would be directed to an address only accessible to the artist themselves.

Our proposed governance model for the bundeskunsthalle.eth domain is likewise very pragmatic. While there are many interesting blockchain governance experiments and technologies to choose from, our proposal opts for a simple, practical administrative mechanism: a multi-sig held by museum employees. The institution can easily incorporate this technology into their existing operational processes without complex legal arrangements with decentralized actors.

Though centrally administered, the transparency of this multisig allows the museum to invite audiences to participate in the governance of specific art economies by coupling the viewing experience with a public evaluation of financial accountability.

Let's have a look at how ENS can be used to map Bundeskunsthalle’s value flows if all transactions were to happen on-chain. The diagram above depicts a simplified art event, with payments to key entities (artists and participants). First the Bundeskunsthalle would send fees to the artist subdomain. The owner of that account would then use those funds to purchase travel, accommodation, raw materials, all that is required for the event, and send the remainder to each artist’s address. With this system, the entire value chain is transparent for everyone to audit.

For institutions looking to decentralize, such transparent finance can be quite intimidating. But we’ve seen in blockchain-based organizations that such accounting can create new standards for shareholder accountability. In practice, high degrees of transparent finance have also sparked more public decision making processes around capital allocation, and greater community engagement at large.

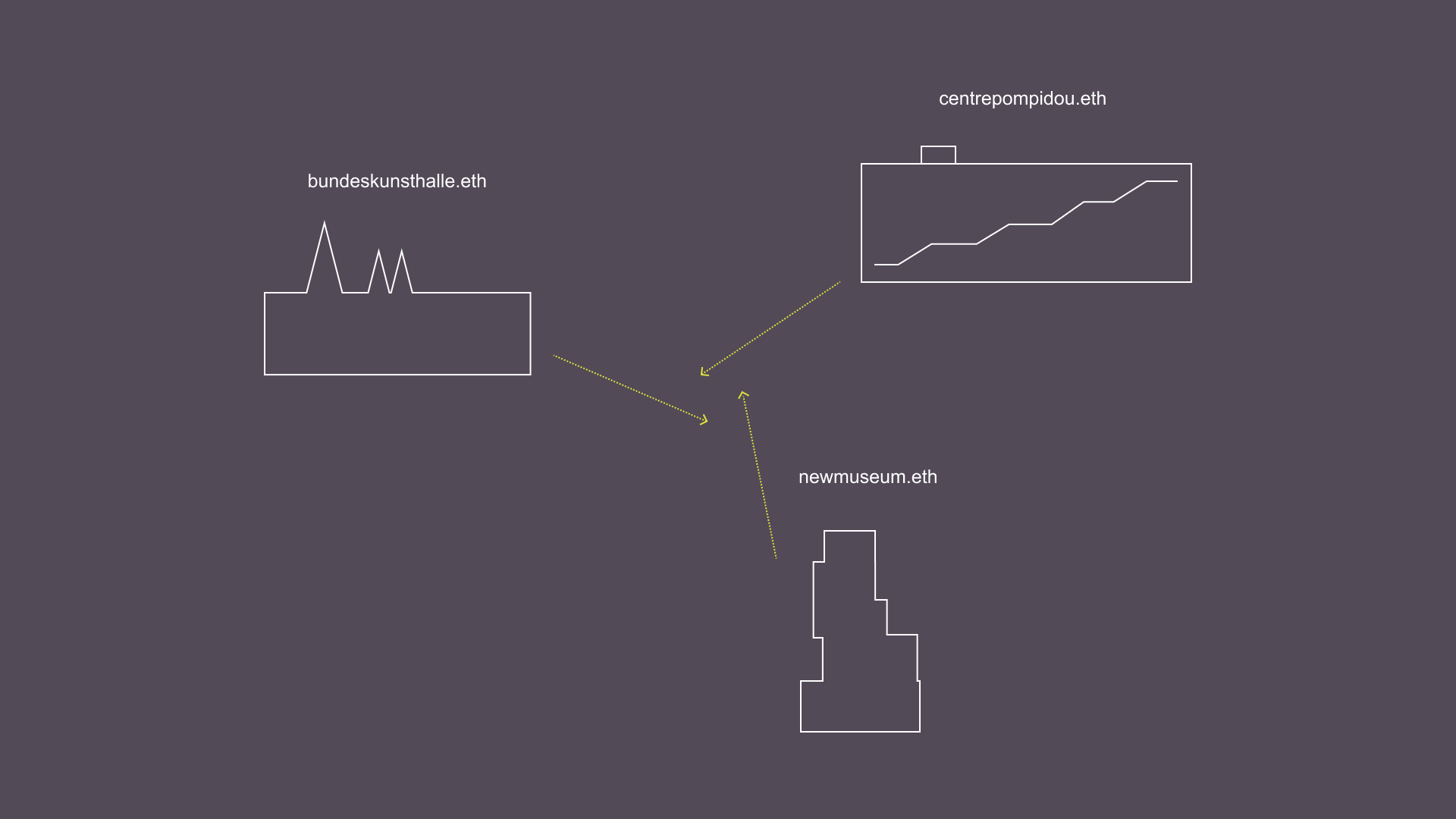

By encouraging contemporary art museums to experiment with similar value flow curation, we hope to initiate a friendly, positive-sum competition among cultural institutions to connect in deeper ways with the material conditions of art workers and audiences. What would it look like for bundeskunsthalle.eth to compete against centrepompidou.eth or newmuseum.eth to showcase better working conditions and compensation to artists and art workers? Or to deploy funds in ways that benefit local communities? We contend that arts organizations who make their own financial flows legible and subject to design can attract a more engaged and enthusiastic public. One notable example is The School for Poetic Computation, a New York-based arts organization that has open sourced its historical budgets and created a dialogue about how to allocate institutional resources.

Yet our proposal goes beyond mere public accountability. In the most radical version, we imagine that the museum’s financial transactions can become subject to artistic intervention with public-minded aims. Framed another way, by moving accounting to the curatorial department, finance can more directly communicate artistic intent, and evolve together with the conceptual or aesthetic dimensions of the work. In an inversion of the usual model, art becomes a framing device for practical redistributive economics.

In summary, curation of financial flows as a medium in itself can bring art closer to its network of local stakeholders and cultivate substantive relations with those communities. By adopting this system, we can move from an exhausted form of institutional critique, with museum as target, to a new arrangement wherein the museum acts as a medium for “infrastructural critique.” Paraphrasing theorist Marina Vishmidt, infrastructure can be understood as a "locus of social relations" that exceed the institution itself.

In our proposed model, public influence on institutional finance is a material outcome, realized in direct cash transfers and solicitation of artworks that benefit those involved.

Positive externalities are effected through socially transmissible patterns of behavior. In this case, bundeskunsthalle’s adoption of value exchange curation can enact a public good by catalyzing positive sum art worlds.

A full video of the Exchange Values event is available on YouTube.

On Public Institutions: A Conversation with Hito Steyerl

Following the event, Laura Lotti and Sam Hart caught up with Hito for a broad-ranging conversation, touching on her years of artistic and theoretical engagements with cryptocurrencies, her recent thoughts on public institutions and the evolution of public-oriented technologies, and her upcoming project “CheeseCoin.”

Sam Hart (SH): Thanks for meeting with us today. We wanted to ask a few questions about the origins of Exchange Values and some of the ideas behind the project. Maybe to start, what first motivated you to squat art institution ENS domains?

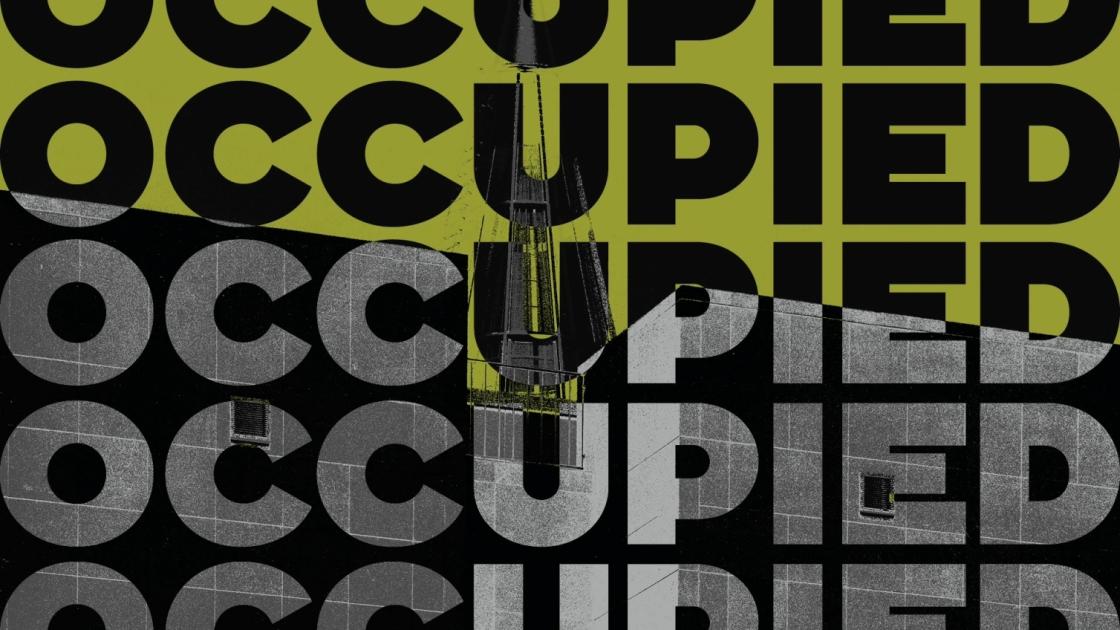

Hito Steyerl (HS): It was sort of a whim, I guess. I knew I had to do a talk at the Royal College of Art in London, which at that point was in lockdown, but they still had a student strike at hand because the college was still trying to take tuition. There were no studio spaces or no activities to talk of, so there was a student strike. Basically, I was trying to roll all of it into one by minting the whole institution as an NFT and giving it to the students in exchange for a larp, which they were supposed to create. Transforming it into a worker, self-managed institution. That was the idea.

When I asked María Paula how to mint this most efficiently she said I should just buy the domain because this would be formatted as an NFT anyway, but it would also have the sort of squatting dimension, which I liked because squatting is also sort of devalidation of a property title. I mean, you're not claiming property of something, you're claiming usage of something. It's not occupying it in the sense that you claim it for yourself. Then, I started minting some other ones at that time. I thought I will maybe use them someday.

SH: Squatting a name as a way to occupy the institution is something we want to ask about as well. Domain squatting has been a practice for as long as there's been domain names, but there's a particular significance to deliberately claiming their name? What pointed you in that direction?

HS: Well, I mean, it's the whole NFT magic. It's laying claim to something. You don't exactly know what it’s supposed to be, but it's supposed to be very strong as a claim. In that sense it was more about probing that kind of claim. By laying claim to a name or domain you're taking hold of the thing itself, which is also the structure of an NFT. Laying claim to a smart contract, what exactly is it you are claiming to possess?

SH: Giving these names to students feels very much in line with the symbolic claims made by NFTs—it's all symbolic manipulation in the end.

HS: Yes, but it's interesting because this is supposed to be directly operational. A smart contract is supposed to directly act on reality and yet here we are in the realm of magic and symbolism and representation again.

SH: Actually, this is one of the things that first attracted me to crypto, how artistic gesture and speculation were married. It seemed like a rich space for artistic experimentation because symbols can so easily transform into material that has real value or meaning for people.

Laura Lotti (LL): There’s also an element of what you were saying before, testing notions of ownership and the limits of property rights. What does it look like when you give a right to use a name to people that are not the holder of that name, for instance? It's interesting how crypto is reconfiguring property in ways we're not exactly sure about yet. Then that's also the big question with NFTs.

HS: Like the brand name, right?

LL: Yes, definitely.

HS: Redistributing the brand name.

LL: We were wondering: what was the purpose of the Exchange Values event and its format with three competing proposals and live audience voting. Was there a specific goal in creating such a setup?

HS: No.

[laughter]

It sort of organically happened because it was built step by step. I think the first thing that was known is that there was a film and it was to be reconfigured by some kind of vote. Then we asked, okay, what are we voting on even? It was kind of obvious to vote about the future of the domain itself and then ask for different proposals on how to transform it. And it seemed to be sort of the obvious step, but I never intended it to be a sort of competition.

Actually, I think this is probably one of the main, if not the only, advantages of quadratic voting. It allows people to weigh proposals, but they don't have to dismiss one in order to decide for the other. That was kind of interesting because I still think that these three proposals turned out to be in fact completely complementary, and one could have all three of them at the same time. This is something which I didn't anticipate.

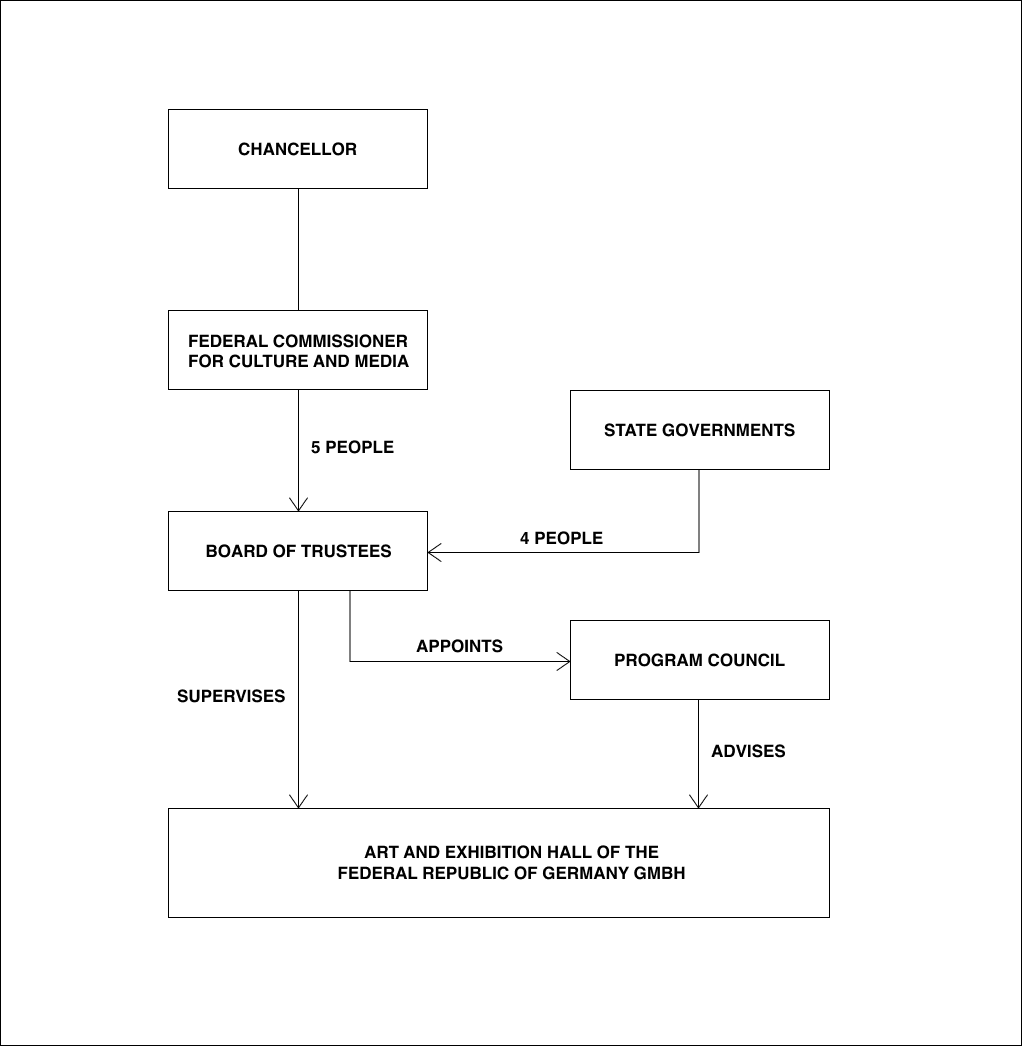

SH: Giving the CEO of Bundeskunsthalle an opportunity to explain the structure of the museum felt very refreshing. As an audience member we rarely get that kind of window into the machinery of the institution.

HS: It's also quite complex. I wouldn't have started with something so intricate, but also I didn't know they are actually a company. I thought they're more like a public institution but they're in fact a company. I didn't know that, it's interesting.

SH: There's a lot of corporate engineering going on in the crypto space in order to connect the blockchain to the real world. Shell structures in the British Virgin Islands or Singapore, with specific bylaws that ensure a one-to-one correspondence between the intentions of a DAO and what happens on paper. So when I saw the Bundeskunsthalle was operated by a private company, which was owned by the German state, I was like, "Oh, okay, I understand this."

[laughter]

HS: Looks familiar. [Laughs] Yes, it's interesting to see that because we keep thinking about these things as public institutions which have some obligation to the public or the taxpayer or someone, but in fact, no, no, no, they are companies. They have an obligation to at least not run huge deficits and so on.

LL: This is actually our next question. Looking at your earlier engagements with blockchain, or video works like Liquidity Inc., there was more of a focus on the relation between art and finance, and that was how crypto was coming into the picture. Whereas this event was a lot more focused on public institutions. We were wondering how this shift came about?

HS: I don't think there's a real shift, because it'd be interesting to create a speculative architecture made out of shell companies. [laughs] No, but I think the thing that I found most interesting in the whole crypto discussion were these earlier governance discussions with Radical Exchange and so on, modes of governance which were quite experimental and creative. Whether they work or not is another question, but I find this fascinating. This infrastructural aspect of the crypto discussion was more interesting for me than selling NFTs, or the purely financial aspect.

LL: Can you give us a hot take on the failure of public institutions?

HS: Well, it's always the same problem. They don't have any sort of real accountability, not all of them. US ones, European ones, the types of governance are very, very different. The bottom line is there is zero compliance in this field. There are no benchmarks, nothing. It's just pretty wild, actually. I was very old when I started selling work, and it was like, [chuckles] "What? Are you kidding? Are you trying to explain your tax evasion benefits in buying my work? Do you think you're very clever in telling me your ideas about this?"

SH: Well I'm not sure crypto has changed that mentality.

HS: Yes, a new generation.

SH: How did you become interested in blockchain as early as 2016? We both remember reading your writing at that time. We re-read prior to the event, and it was surprising how it felt like it could have been written about the state of crypto art today.

HS: This was in a lull right? It was a blockchain winter. It was written shortly after the last crash. In a way, it was much more interesting because the whole speculative animal spirit was decimated, which I found super refreshing. The interesting thing for me, watching from the outside, was to see many structural elements being very similar to how the art world has been configured forever. For me, the core aspect was always to try to find an “algorithm” to simulate or even replace human relations. This is the core paradox for me in blockchain. Is this even possible? I think it's not possible, but the interesting thing is that it forces you to define human relations.

I'm very certain that a lot of things can be automated by accounting and all that. It's actually very beneficial to humankind if this gets automated to some degree. But other things like the slowness of trying to find consensus is very hard to abbreviate or to replace by automated operations.

LL: Exactly. What becomes important also is to define what you don't want to automate, the things that you want to save from this logic. I guess that's also the reason why the tendency to just automate or make decision-making so easy is ultimately not working—because it takes away the richness of people working to achieve consensus. It's never a binary thing.

HS: Of course, in 2016, a lot of what exists today just didn't exist. It was, in a more or less abstract way, speculation of what could maybe come to pass. Now, I think we're in a different reality. How do you see it? I think the infrastructural experiments have been quite marginalized to some degree. I don't know.

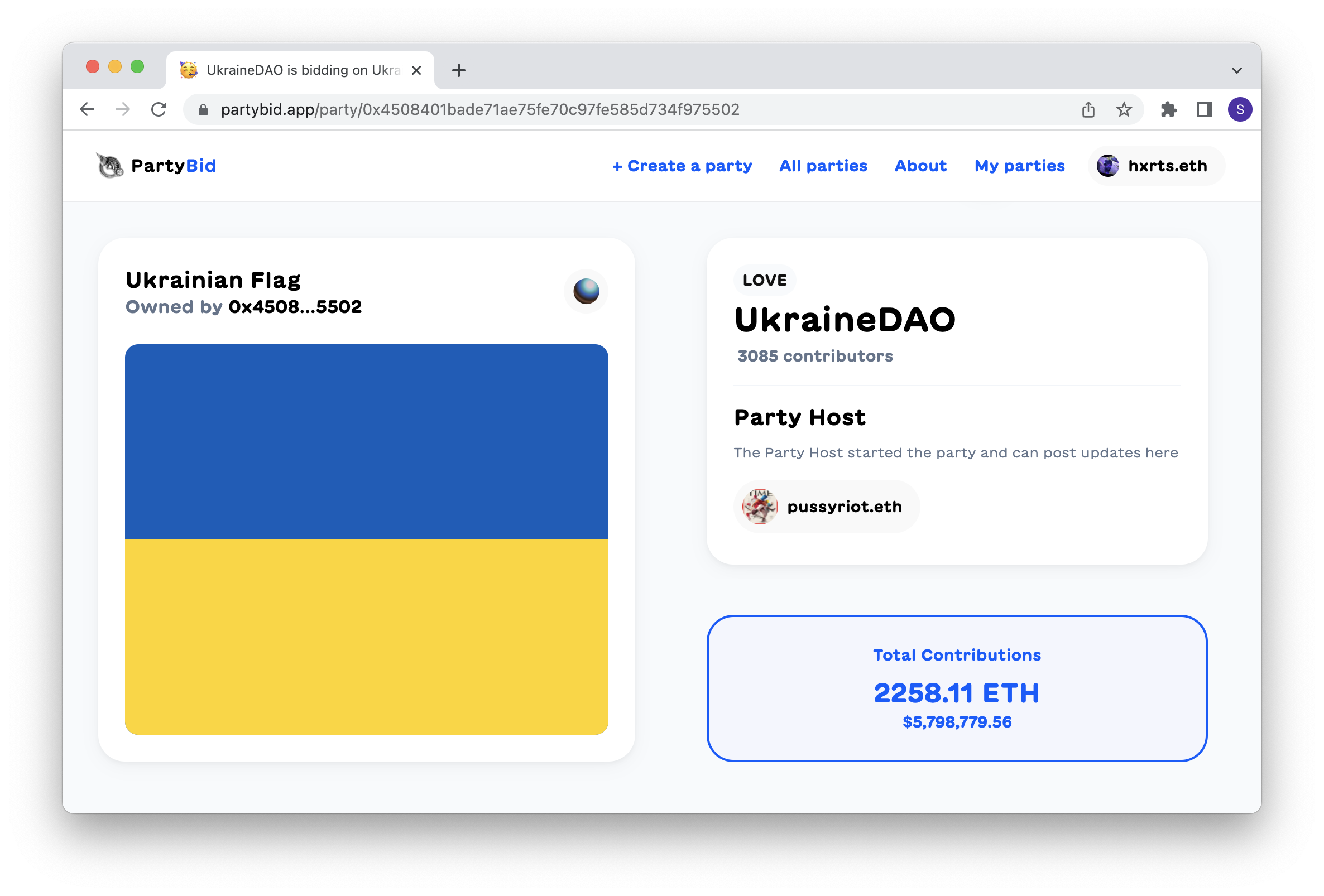

SH: We talk about this a lot. Certainly it’s easier to do digitally native things to start. You can incorporate feedback and iterate much more quickly if everything is software. We anticipate crypto will touch the real world more and more. The Ukraine DAO is one of the first definitive examples. In a matter of days, millions of dollars was funneled into a significant political cause. It's hard to say that crypto isn't having any real-world impact now, but it’s still early.

We're very interested in local governments benefiting from some of the crypto tools being built today. Soon they will be able to select technologies that have been proven out in crypto-native contexts.

HS: I went back to the source of Bitcoin actually. It appears in a collection of alternative currencies that enable local exchange trading systems. The initial white paper was called “A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”. There's a whole different rhetoric to it. It's interesting because there was a whole cosmos, whole infrastructure of all these other alternative currencies which were actually designed for local exchange, but they have more or less fallen by the wayside because of the blockchain boom.

SH: It’s actually the primary project I'm working on. Effectively, a network of local currencies.

HS: You have to tell me more about that, because I'm doing something called CheeseCoin and we're really struggling with that. That's with my friends who are basically shepherds who make cheese. They don't really want to do a cryptocurrency, but they are wondering what kind of fictional currency could help their economy.

LL: It feels like in 2015-16, the narrative was a lot more focused on currency as infrastructure. Now with Ethereum and smart contracts, we have the whole legal economic architecture that can also run without a currency, or in which currency takes on a different role. The scope is a bit different with DAOs. I'm wondering whether the push for new institutions comes from there, or how that's going to happen. Just the facility to raise funds, like UkraineDAO or even ConstitutionDAO, creates the possibility to build something or to really make an impact and shape reality. I'm wondering, how does that relate to traditional institutions like Bundeskunsthalle? They have a whole other different set of problems—the director of the museum was saying that one of the reasons why our proposal could not be implemented was because of GDPR. I was like… okay.

SH: He's not wrong.

LL: He's probably right. But I’d be interested to know if you had any hope, or a specific view, about onboarding these organizations.

HS: No, I don't think I have any strategic vision in that respect. But I think it would really be important for both realms to learn from one another because I think the traditional institutions are quite lacking in self-reflection on what their infrastructure is at all. It's just a heap of bureaucracy in their view. On the other hand, I think there's a notion of public space in the crypto world that does not really exist. This is the empty space between whatever is created, it's like dark matter. Somehow there is no real discussion around it. What is the public in crypto? That's the real question that you're asking in your paper Positive Sum Worlds. This is why I was so fascinated. What do you think is happening?

LL: One of the points of the essay was to show how the notion of the public and good are ultimately terms that have been constructed through historical, social changes, and through the pressure of the state. It’s hard to claim the economic notion of a public good applies to crypto, not because these goods are funded by private capital, but because they're still exclusionary. If you don't have Ether, you cannot participate in a DAO, for instance. That is why in the article we shifted the focus on positive externalities. A conception of the public that is more processual, that takes into account that a public good needs to be created in some form, needs to grow in this new space. We proposed thinking in terms of curation of financial flows as a seed from which to start, to try and cultivate these new notions of public good.

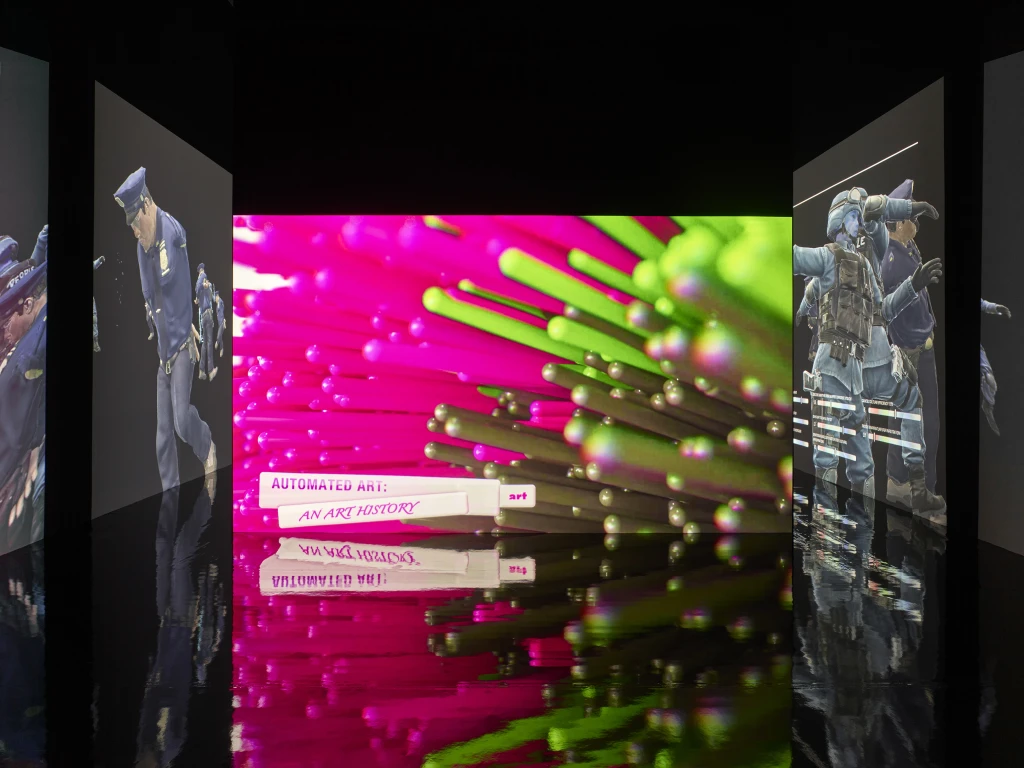

HS: I kept thinking about it. I want to do a show which is purely about its own financial flows, and the beauty of paying people well. There needs to be an aesthetic around this. An aesthetic of financial fairness, that would really be big progress.

SH: The Bundeskunsthalle has a very robust public accountability mechanism. Regulation actually has them pretty boxed in, and I don't think they're very excited about adding red tape. But our proposal aims to reconfigure the accountability model by incorporating it into the creative process. Perhaps it wouldn’t feel so burdensome if accountability was a means of creative expression. This comes back to what we were saying before: feeling like there's an institutional design space that one can shape and make their own.

HS: Also, in terms of discipline, it would be interesting to think about what is the aesthetic discipline for curating financial influence. Is it a kind of water machine maybe, with tubes, and there's different types of pressure? There is no limit to imagining that at this point.

LL: Like a permanent sculptural installation.

HS: Exactly, yes.

SH: Something we were excited about was the possibility of making payments to an art community, and then seeing that community go on to do another project. Making visible the consequences of an artistic and economic engagement with a museum. In this way you can form a circular economy between the museum and the community, and observe this nourishing relationship play out. In this sense our proposal invites institutions to develop healthy associations with artist communities.

SH: In your essay, “If You Don't Have Bread, Eat Art,” you say, "If art is an alternative currency, its circulation also outlines an operational infrastructure. Could these structures be repossessed to work differently?" We're starting to see some of this happen in crypto with programmable artist royalties and splits that are going to cultural workers. The cryptocurrency space is an overhyped mess, but if you’ve seen anything that's of interest to you, we'd love to hear about that. We're also happy to share what we've seen.

HS: Yes, please do, because I haven't followed recently.

SH: I think one of the positive things to come out of the NFT boom is the normalization of artist royalties on secondary sales. This just doesn’t exist in the traditional art world. There's also some interesting experimentation with market structures as artistic media, or modifications of NFT contracts in such a way as to change the relationship with the surrounding art economy.

Automation is also an important theme. Directing a portion of sale revenue to charity for example. I see this very often. Artists can easily add a charity account as part of the sale split to permissionlessly raise funds to a cause of their choice. It's not like the idea is novel, rather the ease with which you can set something up with off the shelf components.

LL: On the other side, there’s also greater access to the art market. I’d never bought an artwork in the real world, but I have a few NFTs made by friends or people whose work I admire, so it facilitates that interaction too.

I guess because it's magic internet money, once you're inside the bubble, you don't think about it. There is a certain detachment. Crypto creates its own locality, or horizon, which makes the bridging with real world institutions something that needs to be addressed. There are tools that are available now. It's also important for more traditional institutions–how could more traditional artists, not media or digitally focused–engage with and benefit from it? There is this project in the performing arts called The Sphere, which is doing a fractionalized NFT campaign on Mirror to basically crowdfund their own real world productions. There are some hybrids that are beginning to happen thanks to the tools. That's quite exciting and interesting.

SH: Crypto has also shifted the window of acceptable discourse. Historically it’s been challenging for artists to talk about what they make, how they make a living. It's often hidden away and that's just not the case with NFTs. Every single project includes a public conversation about fairness. How much is taken by the artist? The price and distribution mechanism. While the conversation is hyper financialized, the art economy is certainly now front and center.

HS: You are describing an art market, which in-part corresponds to the art markets that already exist, except of course, for the new provisions for artist fees and so on, resale fees. But I'm wondering about the whole area of the art world that is informal, educational, nonprofit, and non-market, that happens in all those small galleries. Where is that? Can it even be replicated on a crypto base?

Now it seems to me as if there are a lot of “producer galleries,” let's call them, in the NFT world, which are not run by gallerists, but basically by the people who are making [the art]. But how do we create this other aspect of the art world, which makes art more sustainable in the long run? I think that's still missing. For example, funding scholarships. Or where is the discourse? I wonder what has to happen to reconfigure the base of participation in order for all these things to be able to happen. If funds are channeled to charities, which is great, why not to writers or something? Which are not paid to please galleries, collectors and auction houses, but to develop some proper serious discourse.

LL: Yes. What do you think that would be?—because another phenomenon that we're seeing now is that a lot of these protocols and DAOs launch tokens and they have huge treasuries with billions of dollar value. It's ridiculous because they almost don't know how to spend their money.

[laughter]

Crypto-philanthropy is becoming a conversation, as well as public goods. Do you think that the current art world, or these milieus–the educational aspect, the collaborative aspect–would they welcome funds coming from some of these decentralized protocols?

HS: I don't know, honestly. In Germany, they would have huge regulations, but in other places maybe not. There would be a concern about artwashing real existing tax evasion obviously. Maybe that's not even the main point—to collaborate with already existing institutions—but to recreate a public sector, which is transversal, also not run by the nation-states.

SH: The “public sector” is very attached to the nation-state, another exclusionary fiction.

HS: It is a fiction. Absolutely. I think it's better to diversify the different spheres that are addressed, instead of just operating everything on the market template. In reality, there are also other areas. All sorts of different other networks are playing into human relations. I don't know how a crypto economy would address non-market oriented human networks. The experimentation we did is really, really modest. But experimenting with all the different types of congregation that can happen around these ideas... Our gathering was not organized around the idea of a market at all, yet it employed some tools or ideas from that space.

SH: One of the most important aspects of public institutions is the implicit identification of a constituency. Asking what is good for that group? One that’s not strictly a market.

[children’s laughter]

HS: Children, for example.

[laughter]

LL: Playgrounds. We need more playgrounds.

SH: The ideal public good.

[pause]

LL: I really like the idea of constructing and maybe narrating alternative futures about the public that are more transversal. Blockchain tools can provide some of these extra-state conduits for bringing together groups that share the same needs, the same visions and desires, but that maybe don't speak the same language, don't have the same nationalities. All this is becoming a lot more possible.

SH: Yes, something we discussed quite a lot while writing was a desire to make a more inclusive, global public—but in doing so, by defining that wider constituency and asking what's good for that public, you immediately end up in a colonial mode of determining what's good for others.

HS: Okay. Let's face it, plumbing is always good.

[laughter]

No, but it's absolutely true. You cannot really define the public for anyone. It has to emerge or be created through ruptures and so on. Even creating the space for those ruptures to potentially happen is important.

SH: One way to escape the trap of coloniality is the creation of a solidarity economy.

HS: We ran some small experiments with my students to “design a solidarity economy.” Really interesting problems started arising. For example, you need to have a strong gamification aspect or people won't participate. But if you have a strong gamification/competitive aspect, then you start to quantify solidarity somehow. This creates a different problem. I'm really curious how to work through all these paradoxes.

LL: The question of scale also becomes really important for these global DAOs. There is a level of trustlessness that needs to be maintained, or there needs to be guaranteed security of the system. Whereas for artist communities that are locally situated—where people know each other—there is maybe more room for experimenting with protocol mechanisms without necessarily having to embrace the whole blockchain infrastructure.

Blockchain becomes really important when there is value transmission happening. At the level of decision making and sharing physical resources, the blockchain itself is often not necessary. It is more interesting as a conceptual object, or to attract institutions that would want to engage with these ideas.

There is also a big difference between these protocol communities and how artist communities operate already without tools. The problem of on-boarding becomes really important. Practically, at the hyper-local level, there is little need for a blockchain, unless then these small nuclei want to connect to each other.

SH: That's a crucial point. To participate in the local cheese economy your friend may not need a blockchain. However, it might if you want your local economy to be legible to the local milk economy. That standardization and interoperability aspect is where the technology does actually become important.

HS: In the case of the cheese, I think our solution is not to use it as an operational tool and definitely not as yet another product in the current hype market, but as a narrative device. Trying to describe cheese making as some sort of organic blockchain really. Cheese is a real life decentralized autonomous system! You have a lot of participants, bacteria, slime molds, the smell, the enzymes, blah, blah, blah and so on, which are engaging with one another in “chemical smart contracts” if you like. It's also interesting because then you get to map all the components of the system. It's not just people who have resources and the goats, grass, amount of wolves, wildfires and quantity of milk, but also relations that have become important and part of the system. You can use this map of a system to track, not whether it's profitable or efficient, but to narrate the state of it. Cheese is a smart contract. It's not very smart, it's a smelly contract. I think of it not as the Internet of Things but the Intranet of Stink.

SH: Last question. This one’s a bit of a joke. There's this fractionalized Doge meme—like the original Doge image has been fractionalized into a coin. Pure art-as-currency. Not really the alternative currencies you meant in your original essay, but it's where we’re at right now: fractionalized memes. So where do we go from here?

HS: I don't know, but it is a fact that around 95% of the energy in the space is devoted to fractionalized Shiba Inu memes that burn the planet as collateral. Recession is always great and precious, because then for a while, you get rid of this energy. I'm maybe less shocked than you are, but on the other hand, maybe I'm also less disappointed. Because it was a very real possibility from the beginning that something similar was going to happen. What do you think?

SH: I wasn’t all that surprised either. It is 95% of the activity, but I feel like we're trying to focus on some of the more interesting alternative infrastructures and encourage experimentation in that space.

LL: Also because there is a lot of monetary value that is now stuck in this very small ecosystem, and there's almost no better way to spend your internet money than buying memes. Because trying to get out of this virtual economy is also a hurdle–cashing out, taxes, how to even do it… tooling is still very minimal and there is also not much awareness or culture. Those are the hard things that need to be thought through and experimented with even before they can be realized. Maybe it's not surprising that the very first use case—

HS: —is war, buying RPGs.

LL: Yes, because it's easy. And there are a lot of people in that echo chamber. But I think it's really energizing that there seem to be more and more interesting initiatives, and awareness of the limits of a lot of these mechanisms.

HS: Even if it's not useful, it's sometimes really interesting. I was really fascinated by the narrative emergence that happened around things like Loot for example. That people started just fabulating on their own. That's also something really interesting which is not useful or immediately profitable, it's not financial, it just happens. I find this very inspiring.

SH: We were fascinated to watch that play out as well.

HS: A franchise without a franchise. You already do the spin off and prequel before the story's even written. That's interesting.

LL: Yes. These experiments challenge the utilitarian view of economics. Loot or Shiba, they don't have any use. They testify to the performativity and collective nature of value.

SH: If nothing else, the technology has made some of the very bureaucratic systems a little bit more palatable and exciting, for young people in particular, to engage. Like Cheesecoin. Maybe it doesn’t need a coin, but tokenization can open an important space for discussion about value, exchange—

HS: —and systems.

SH: Symbolic power is worth something.

LL: Exciting. Wen Cheesecoin? When can we ape?

[laughter]

©2024 Other Internet Research Institute