Introduction

It’s been well over a decade since the publishing of the Bitcoin white paper. During that time the crypto industry was born. Hundreds of new blockchains were released. Total valuation reached the trillions. Millions of evangelists were mobilized, as were millions of skeptics. Still, there is no clear consensus when it comes to the most basic question that has surrounded it all. Is crypto good?

The question is particularly cutting at the time of this piece’s writing — during a sharp macroeconomic downturn that for some is prompting the question of whether or not crypto will even exist a year from now, not to mention its effect on society. I think and hope that many of the spurious manifestations of crypto disappear in the near future. But it’s clear that the collective themes that comprise what we call crypto are not going anywhere. The web is still largely centralized. Moving money online still requires third parties. The ownership of digital objects is still obfuscated. Problems like these will continue to be solved, and those building the solutions will continue to see financial upside. It’s about more than any one blockchain. Just as crypto is breeding a new class of technology, it’s breeding a new class of technologists. These are people who desire to change the world, and armed with money from their world-changing ideas, this desire will only intensify.

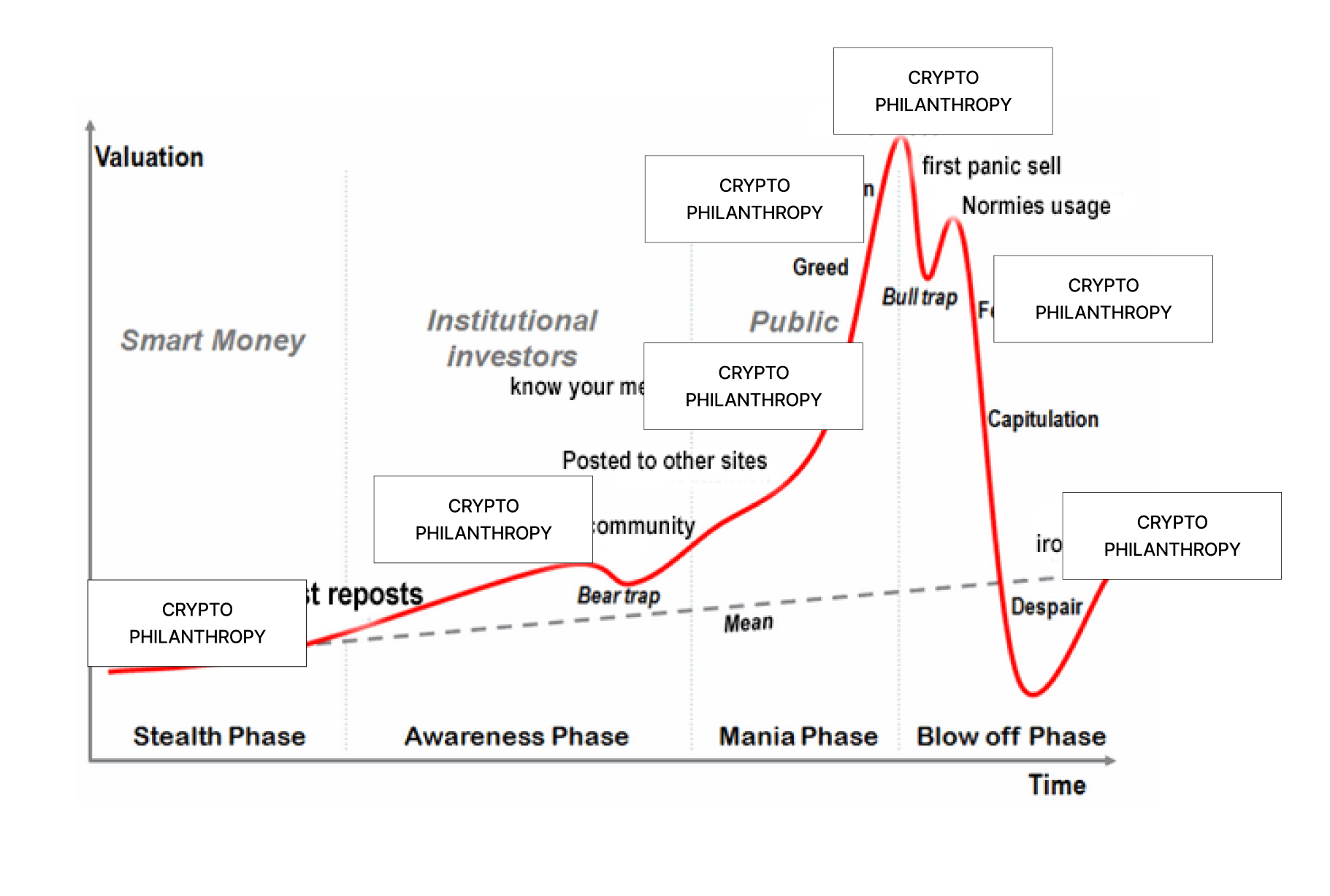

Enter crypto philanthropy. More than just another imagined vertical in an industry that’s rife with them, crypto philanthropy can already be touched and felt in a way that the metaverse cannot. Back-of-the-envelop estimates suggest that annual giving under its banner has increased from hundreds of thousands of dollars in 2017 to billions dollars as of 2022. That collectively places crypto philanthropy on the scale of some of the world’s largest foundations. It’s now the central issue of podcasts, conferences, and organizations (lots of organizations). This isn’t even to mention its reverberations in private arenas where philanthropic discourse is often most cultivated.

This report will begin by taking readers through the short history of crypto philanthropy. How has crypto led to so much wealth? Who are crypto philanthropists? What tools, infrastructure, and mechanisms for wealth redistribution has crypto brought about? After establishing this baseline, the piece will discuss the emergent behaviors that lie on top of it. What types of things are crypto philanthropists funding and how? Finally, the implications of this new philanthropic paradigm will be considered. What is its legacy? How can it be the best version of itself?

Philanthropy, despite its Davos-adjacent reputation, is more than charity-galas and virtue signaling. It’s an unavoidable and understudied attempt at progress—and in its crypto sub-variety it’s already well on track to impact the livelihoods of millions of people, regardless of crypto’s current macroeconomic fortunes. On one hand, this piece is for anyone looking in on this strange new world from the outside, curious about crypto philanthropy and its mixed impacts on the world.

Critically, this report is also for crypto workers and aspiring philanthropists. While it has strayed from its early zealotry, the crypto industry still finds itself in period of hope and romanticism. As much as crypto’s devotees are lured by making money, many work in crypto because of its world-changing potential. But the last few years have shown that there are limitations on crypto’s achievements when their impact is assessed only on the basis of its technological merits. By understanding crypto philanthropy, we can arrive at a more expansive view of crypto’s influence on the world, and in the process form a more direct answer to how it might be improving human welfare. We may not ever be able to answer the question ‘is crypto good?’ but with crypto philanthropy we can at least study the thing that gets us closest to the question.

What is crypto philanthropy?

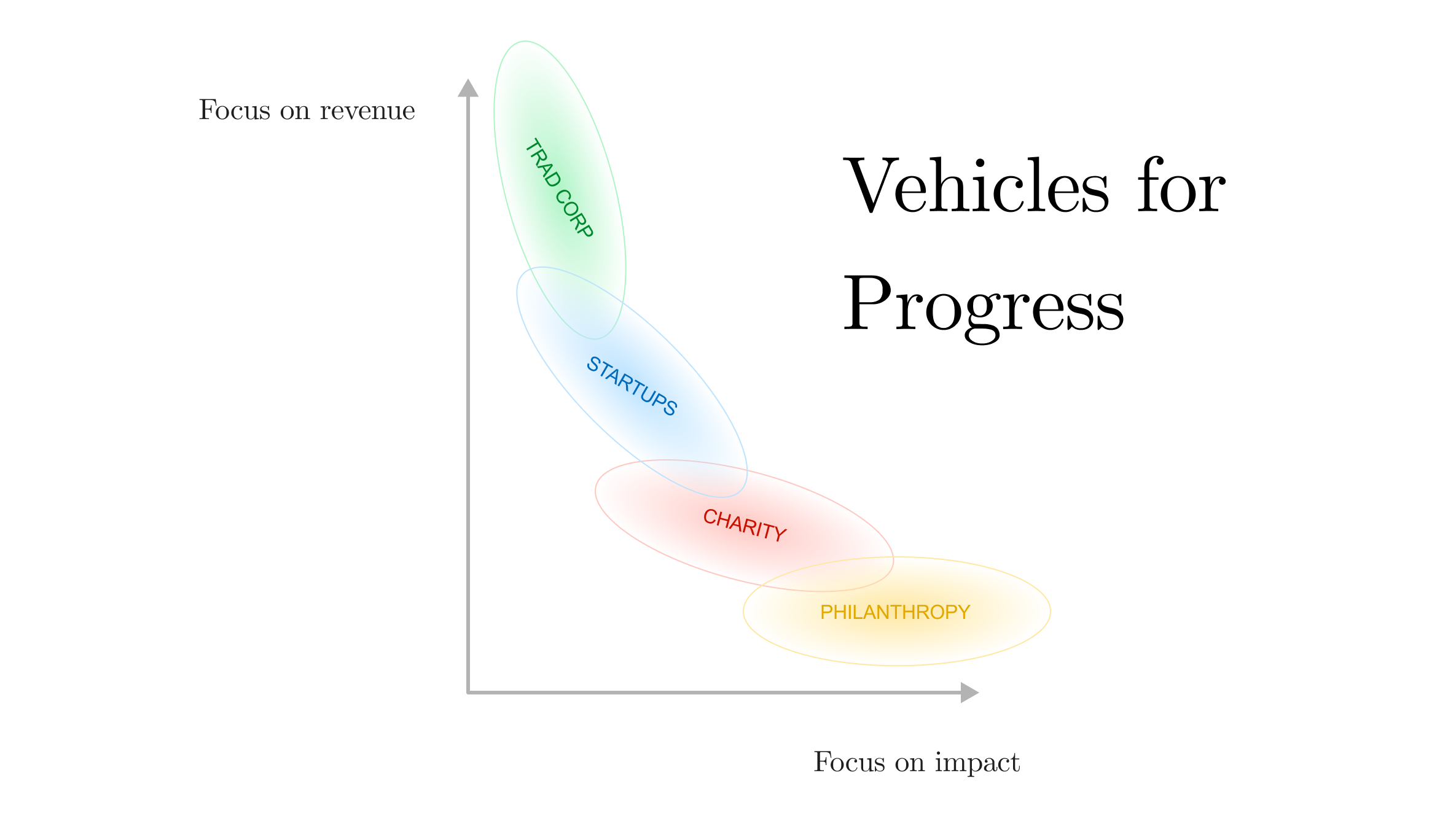

The philanthropy component of crypto philanthropy concerns itself with allocating unrestricted capital towards the improvement of society, life, the physical world, and everything in between. It’s an intentionally open-ended and self-defined act. Philanthropy, which can be associated with a proactive funding of societal progress, is not quite the same as charity, which can be associated with a reactive provisioning of assistance to those in immediate need, although a reasonable overlap between the two exists. All philanthropy is about doing good, but not all acts of doing good are philanthropy.

As Nadia Asparouhova puts it, “if venture capital is risk capital for private goods, philanthropy is risk capital for public goods.” In an industry like crypto where public goods are generated by for-profit entities, it’s only inevitable that true public goods become deprioritized. Philanthropy is a way of refocussing on the things most worthy of funding.

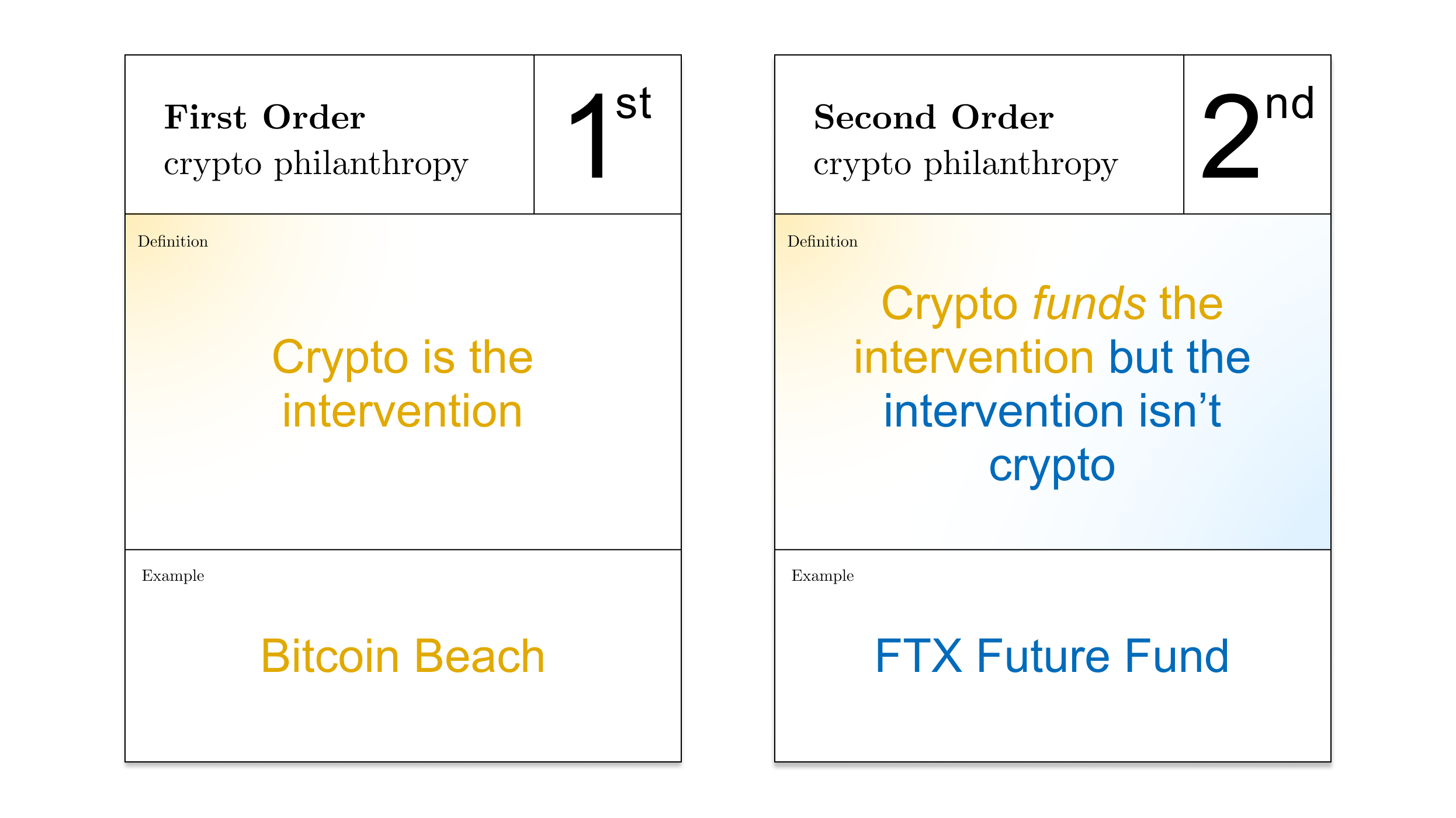

Most logically, the crypto in crypto philanthropy refers to using blockchains and their cousin technologies as tools themselves to achieve impactful outcomes. A commonly cited example is peer-to-peer financial transactions which can help individuals avoid predatory middlemen. Another example might be the potential crypto holds for advancing cryptography and as a result digital privacy. Finally, crypto in its broadest ‘on-chain code’ and ‘off-chain community’ definitions has led to novel ways of pooling and distributing charitable funds. We can call all of this ‘first-order’ crypto philanthropy.

Less obviously, crypto also refers to using the technology’s ability to generate wealth and then organize and reallocate it towards initiatives that don’t necessarily have anything to do with crypto. Think of an early Z-cash investor who used some of their wealth to build a school for orphans in Nigeria, or Vitalik Buterin funding longevity research. We can call these things ‘second-order’ crypto philanthropy.

Piecing these definitions together, we can begin to understand why crypto philanthropy is more than the combination of two buzz words. The pursuit of positive impact is fundamental to crypto’s past development and current appeal, despite this aspect being blurred alongside more nefarious use cases. Yet even if crypto maintained no connection to first-order impact, it would still have high philanthropic potential. We can attribute this to the sheer amount of new wealth crypto has generated, and the inevitable downstream and off-chain flows of this wealth into philanthropic causes.

Crypto philanthropy should thus be thought of as a new philanthropic paradigm, similar to the upheavals that rode on the coattails of previous technology-driven wealth booms. Just as the gilded age industrialists and tech innovators of the 21st century cemented their own mechanisms and styles of philanthropy, so will the victors of the cryptocurrency boom we are currently in the midst of.

We know this because it’s happening already. In the individualistic world of philanthropy, all it takes is one especially altruistic person to create a flood of philanthropic outcomes that materially change the world and set precedent for others to follow. Consider the enigma of Sam Bankman-Fried, the CEO/founder of FTX and youngest billionaire in the world at the time of his minting. Bankman-Fried openly declares the ultimate goal of his crypto efforts as ‘earn-to-give,’ a style of philanthropy aligned with the effective altruist movement (described more below). His net worth is tens of billions of dollars, and to a modest extent it’s recession-proof. It’s hard to overstate how much of an influence SBF’s niche set of beliefs will have, and he’s only one of dozens of individuals in crypto who hold such levels of influence.

Not every act of philanthropy looks like SBF’s effective altruism though. Just as traditional philanthropy can become empty signaling, so can crypto philanthropy. In fact, as we’ll see later in this piece, much of what we can call crypto philanthropy fails to live up to the high bar set by Bankman-Fried.

We study and analyze philanthropy because it’s a discipline that often evades the public gaze, despite being fundamentally concerned with the public’s welfare. Because philanthropy takes place after someone becomes wealthy, it tends to be contextualized as the dessert instead of the main course. But for the individuals who are impacted by it, this framing is irrelevant. Philanthropy can spawn equally uplifting and horrifying outcomes. Yet because it is often illegible, we have a hard time properly judging if it is pursued for the right reasons, or if it’s having an effect at all. In an industry like crypto where so much emphasis gets placed on the radical potential of the technology itself, shifting to a philanthropic-centric definition of impact allows for more holistic perspective on how crypto can benefit society.

Crypto yields wealth, wealth yields philanthropy

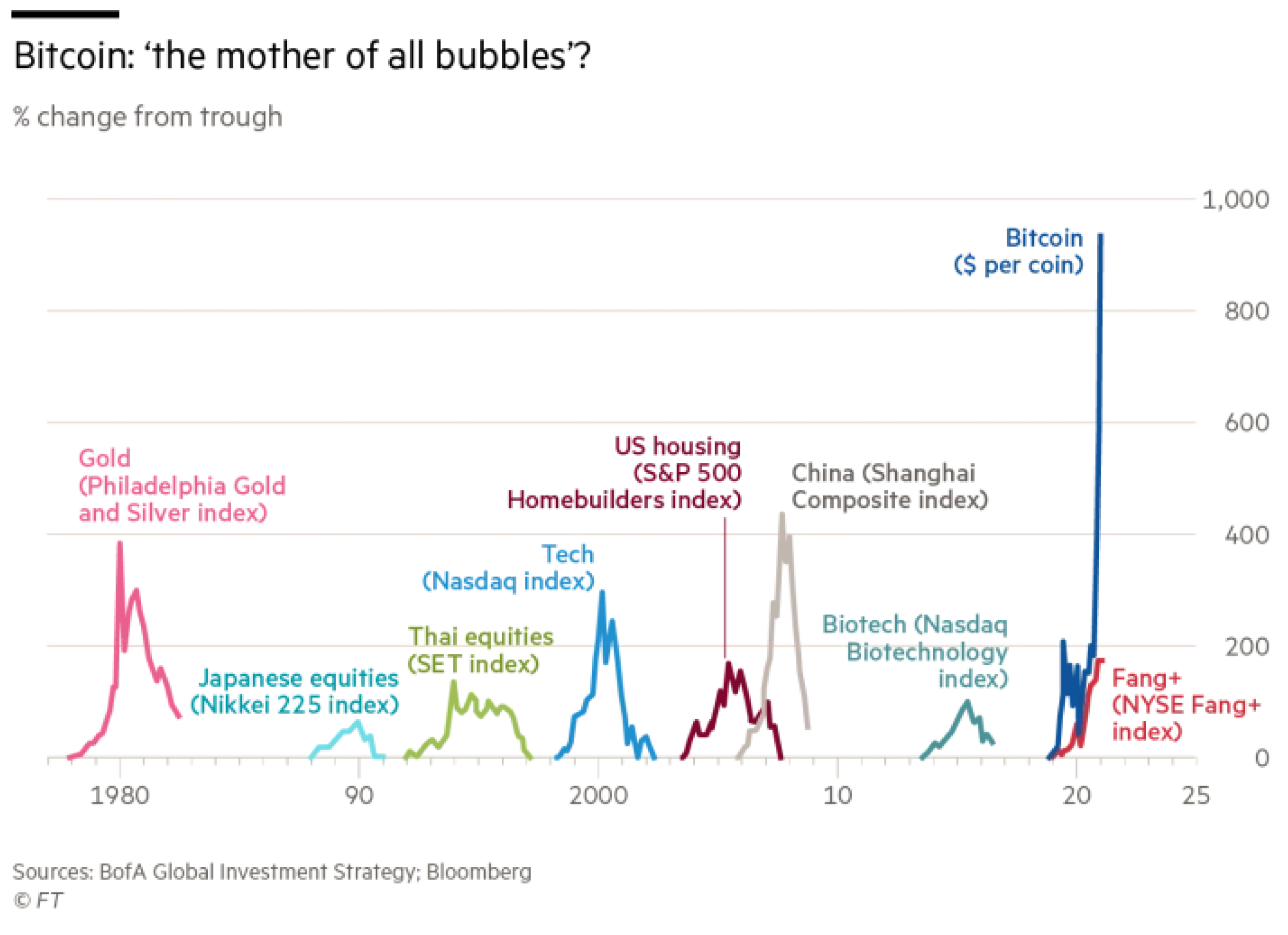

The first thing to note about crypto is just how wealthy it has made certain individuals in a relatively short period of time. Rapid wealth accumulation is a given of speculative bubbles. But is crypto a bubble? If so, it doesn’t quite fit historical precedents.

While manias like the tulip or railway mania experienced just one clear speculative boom and bust lasting several years, crypto’s speculation has lasted for well over a decade. There’s the Bitcoin bubble, but there’s also the ApeCoin bubble, and they are simultaneously correlated yet entirely different.

The point to be made here is whether you call it a bubble, mania, or Cambrian explosion, crypto has found a way to well up over a trillion dollars of value at its recent peak, and at the present downturn still at least hundreds of billions. It’s aggregated this value towards individuals who are comfortable taking incredible risks. The typical portrait of a philanthropist is that of a middle aged industrialist whose steady hand over the course of a career grants them the expertise and capital to start their own foundation. What happens when this image is instead a kid in their twenties who took a couple of good bets and went from poverty to generational wealth in only a couple of years?

On the lower end of the crypto wealth spectrum are individuals whose main interaction with crypto is in the form of retail investment, day trading, and various liquidity provision positions such as yield farming. For the fortunes made in crypto in the range of hundreds-of-thousands to millions — a very large amount of money relative to the average world citizen, but not a unfathomably large amount in the context of philanthropy — we see little desire to give this wealth away. This is due to intuitive pattern of spending one’s wealth on personal matters before the thought of intentioned giving. It deserves to be said that the meme of bitcoin-purchased steaks, yachts, and ‘lambos’ is a sincere motivator for many in crypto. Less hedonistically, there are anecdotes about paying off student loans, or buying houses for moms. When altruistic behaviors do enter the picture, it tends to be in the form of charity before it is philanthropy.

Crypto has yielded many individuals who have won the game, even despite the short term fluctuations of markets. For this group, their wealth was born from not retail investments but actively contributing to companies and infrastructure in and around crypto. Individuals like like Brian Armstrong, Changpeng Zhao, or the previously-mentioned Sam Bankman-Fried have grown fabulously wealthy through the creation of cryptocurrency exchanges. Another common earning pathway is wealth appreciation via protocol creation and/or management. Hayden Adams, creator of Uniswap, and Vitalik Buterin, creator of Ethereum, own hundreds of millions of dollars of their project’s tokens. All these individuals have to various degrees begun to engage in philanthropic behavior, the nature of which is discussed below.

Historically it has only been this type of billionaire which has pursued serious philanthropic endeavors. But crypto appears poised to change this by enabling those in lower wealth brackets to more easily coordinate around pooling and distributing capital. Might this be setting the financial threshold for capital-P philanthropy lower than it’s ever been?

Crypto yields new wealth distribution mechanisms

In the context of crypto where wealth has been generated “on-chain” (mainly in the form of crypto assets), we need to understand how this wealth eventually moves into the hands of organizations and individuals who can drive impact. Crypto has developed novel capital staging and aggregation mechanisms, as well as usage patterns and interfaces that sit over them, that guide this process.

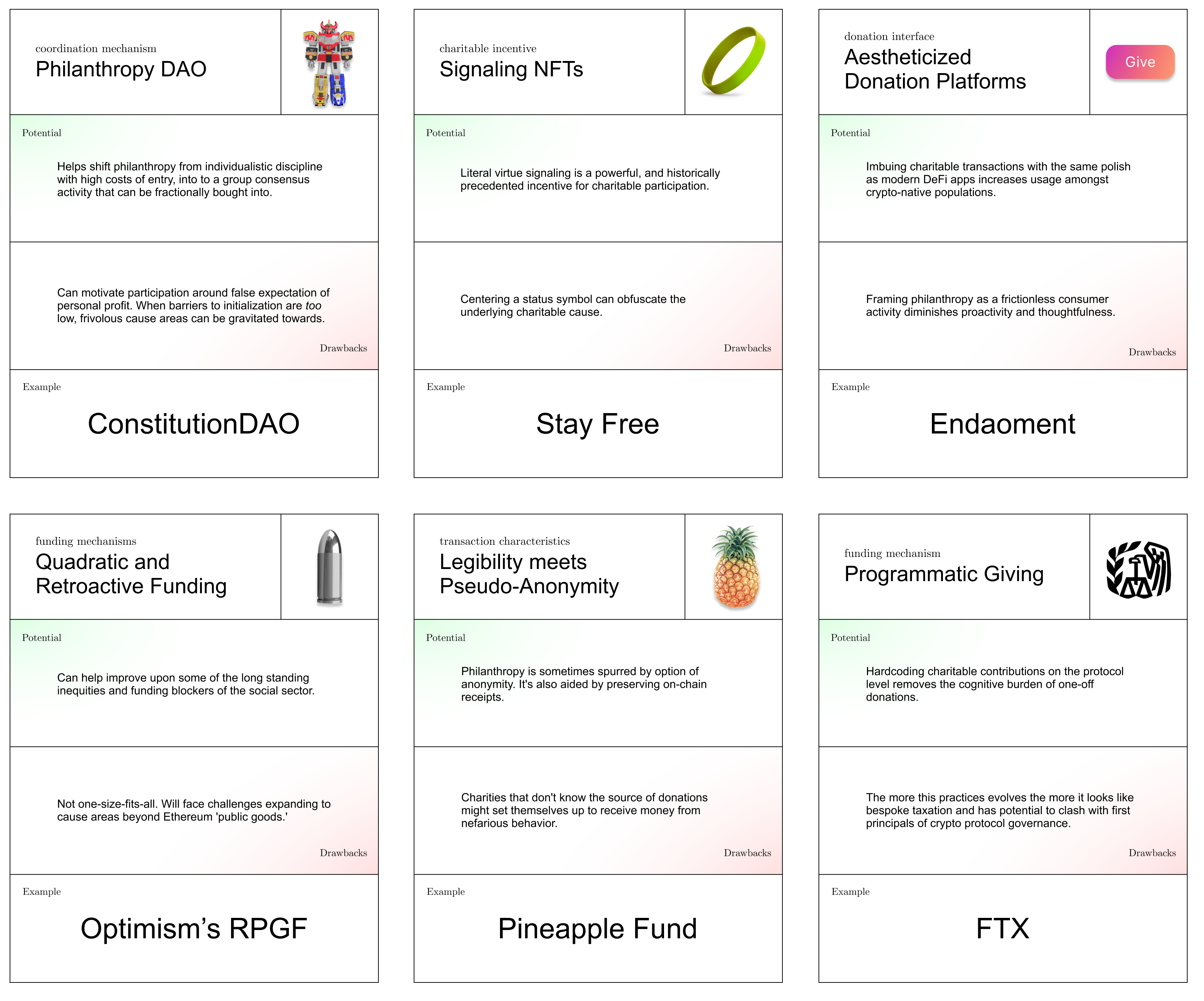

DAOs and other collective decision making bodies have the potential to evolve the practice of philanthropy beyond its reputation as a closed-door, individualistic discipline. Whether they are conscious of it or not, many DAOs already are participating in philanthropic practices.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, there are still plenty of individual donors. Sometimes they even are anonymous. They too are influenced by novel ways that philanthropic capital can be moved around in crypto.

It’s crucial to make legible all these reference points as novel phenomena with real implications for social progress, even if at the moment they seem like passion projects for crypto in-groups.

The mechanisms of crypto philanthropy, at a glance.

Crowdfunding, DAOs, and accidental philanthropy

The crowdfund is a central transactional primitive in crypto. Crowdfunding is not a new concept by any means, especially in altruistic contexts. But crypto adopts this primitive and manifests it in both its ideology and its technology. ‘Together we can buy anything, own anything, and therefore do anything,’ the sentiment seems to be. This is further spurred by additional tools for streamlined financial coordination such as multi-signature wallets and group bidding platforms. All together these tools distill in crypto users a sense of economic alignment regardless of trust, permission, or levels of financial contribution. Merely having a shared interest is sufficient cause for collaboration.

The concept of a DAO has become a monolithic catch-all for any type of coordinated group in the context of crypto. This is partially due to its flexibility. DAOs are more than just a shared wallet. They are composable into many different arrangements, from social clubs, trade groups, to individual firms; merely having shared interests is sufficient activation energy to form a DAO. One such composition a DAO can take is the crowdfunding DAO. In this formation, participants coordinate to crowd-raise capital for the sake of collective purchasing power.

A notable example of this type of DAO is ConstitutionDAO, which pooled funds using a tool called Juicebox to attempt to purchase a copy of the US constitution. Similarly, SpiceDAO raised funds for the purchase of a copy of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune. Even though only SpiceDAO successfully purchased its target, the learnings from both of these organizations are the same. Because US securities law blocks the sale of business assets to non-accredited investors, participating in these types of crowdfunding DAOs does not confer fractional ownership of a legal entity that in turn owns capital such as a rare book or document. Instead participants are granted governance tokens which only represent control over the strategic decisions that guide the stewardship of the owned asset. As such, these organizations actually can be seen as a form of philanthropy based on the idea that funds are being pooled purely for the sake of stewardship or advancing ideology. With crowdfunding DAOs, a sort of accidental philanthropy replaces promises of financial returns.

Of course, the philanthropic principle behind SpiceDAO and ConstitutionDAO can also be applied in more intentional use cases, where users clearly understand that they are funding some initiative purely for the sake of it. There are inklings of these types of DAOs popping up that fund cause areas such as scientific research (more on this below). While their on-the-ground efficacy remains largely unproven, by introducing mechanisms for group coordination and capital pooling, DAOs become an interesting foil to the traditionally individualistic practice of philanthropy. DAOs are compelling not just because they lower the entry cost to philanthropy, but also because they experiment with group decision making. Instead of philanthropy being dictated on the basis one individual’s preferences, many individuals can bring a more nuanced conversation to the table.

Accordingly, we also are seeing the first signs of DAOs that don’t collectively fundraise, but collectively distribute funds. Using their governance functions, DAOs are being used by nonprofits like Big Green to facilitate grant-making. It’s uncertain how when implemented this model will improve upon the standard non-crypto structures of nonprofit management. For Big Green, their aspirations are for the DAO to act as a leveling mechanism, subverting the relationship between grant makers and grantees by offering up voting power to practitioners who otherwise would be on the tail end of strategic considerations. It’s possible that DAOs could improve upon these sorts of age-old problems that grant-making bodies suffer from. It’s also possible that ‘impact DAOs’ are just an example of everything looking a nail when you’re holding a hammer. It’s only through tight feedback loops between the busywork of philanthropy and its real-world effects on beneficiaries that impact DAOs can avoid this fate.

NFTs —tokens of altruism

During a brief period of time in the American mid-2000s, it seemed like everyone was wearing yellow rubber bracelets engraved with the word “LIVESTRONG.” The bands, manufactured and sold by Nike in support of Lance Armstrong’s Livestrong Foundation’s cancer research efforts, were equally a fashion object as they were a token of one’s altruism. The marketing ploy all together raised north of $100m, proving that when positive moral reinforcement meets social signaling pressure, the result can be a significant altruistic outcome.

With the upswell of adoption of NFTs, we’ve seen fragments of the lessons learned from the charity bracelet era. Just as much as NFTs can act as individual artworks, they also can act as participation badges and in-group signaling functions. POAP (Proof of Attendance Protocol) NFTs have served as popular ways to signal to others that you attended events and conferences (usually of the crypto variety). Displaying ‘PFP’ (profile photo) NFTs as one’s twitter avatar is another example of the powerful signaling effects NFTs take advantage of. Similarly, it’s not hard to imagine NFTs that signal virtue or altruism. As it turns out, plenty of these tokens exist and they actually account for some of the highest prices ever fetched by NFTs. Here are four examples.

While NFTs like the $6m Snowden NFT capture the crypto equivalent of a premium gift package at a high status charity auction, it’s interesting to consider the viability for philanthropic participation NFTs, or possibly just copies of the same fungible token, that line up closer to Livestrong Bracelets. At the moment, it doesn’t appear that these types of token would be all that powerful signaling functions. Their ability to be displayed and confer positive associations on their owners is stymied by the general nascency of token display interfaces. The only places one can really show off a NFT are NFT marketplaces and Twitter. But it’s not difficult to imagine a future where token ownership is more publicly legible, and carried out by populations beyond just crypto enthusiasts, in which case we might see similar dynamics play out as did with Livestrong bracelets. This is, after all, just another version of the same dynamic being played out in the fledgling world of digital fashion.

The aesthetics of DeFi flow into donation platforms

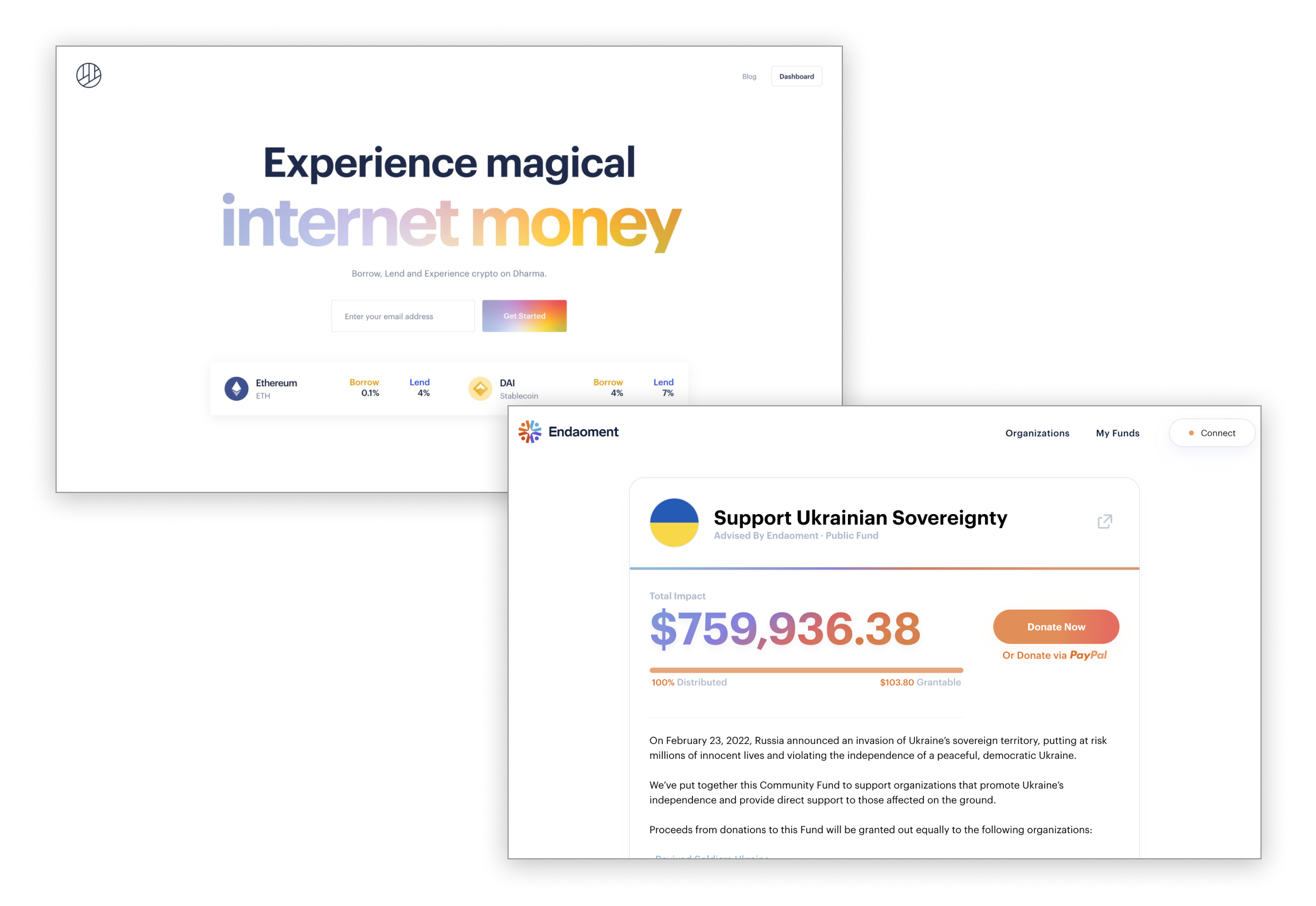

Crypto embraces composability both on-chain and off-chain. On-chain primitives like DAOs and NFTs are accompanied by off-chain customs, behaviors, and aesthetics. Chief among off-chain customs in the world of crypto are the polished interfaces and wallet-centric user experiences of DeFi platforms. Think one-click transactions, rounded corners, bright rainbow gradients. The ubiquity of the web3 aesthetic has meant that it’s begun to find its way over to crypto-adjacent products like donation platforms that don’t have all that much to do with DeFi.

One of these apps (top-left) is for finance. Another (bottom-right) is for donations.

Looking at one of the more prominent crypto donation platforms, Endaoment, we see the web3 aesthetic on full display. Another popular donation platform, the Giving Block doesn’t quite reach the same levels of interface polish as Endaoment, but it preserves the web3 UX principles of simplified transaction triggers and a general appeal to a more financialized style of giving (for instance, Giving Blocks offers “Impact Index Funds”).

The presumed hypothesis behind crypto-native giving platforms is that they drive increased donations by appealing to a chameleonic symmetry with the DeFi platforms they take after. Yield farming has nothing to do with choosing and donating to a charity. But if these two types of transactions are only mirrored on an aesthetic level, it allows for a users coming from a DeFi background to feel like they are yield farming while actually donating to charity.

In crypto there are donation platforms that look like DeFi products, and there are also DeFi products that take on characteristics of donation platforms. At the simplest level this manifests as a flow adjacent to the transaction layer that allows for users to make small donations, similar to coin jars in the checkout aisle at a grocery store. A notable example is Uniswap’s donation ‘swap’ feature that was released in support of Ukrainian war efforts. The principle that underwrites this donation mechanism is a simple one. Get as close as possible to the flow of money and let some of this trickle down to philanthropic causes. The same thing that makes this strategy effective — its high volume, low success rate formula — is its drawback. Sometimes passive philanthropy is appropriate, but sometimes philanthropy requires deeper considerations and more intentioned financial contributions than a streamlined penny jar checkout flow can offer. Maybe wartime aid isn’t actually the best thing to ape into? Or even if it was, maybe it’s deserving of more than table scraps?

Uniswap’s charity ‘swap’ feature.

Programmatic giving and protocol treasury dispersal

FTX, Sandclock, Pupper, and Bail Bloc all take (to various degrees of seriousness) this transaction layer concept one step further by hard coding charitable contributions into the base logic of their use case. For Sandclock, this means programmatically converting yield earnings into tax deductible donations for preset charities. In the Bail Bloc example, users could use the spare computation power of their personal computers to mine Monero which then was automatically donated to a nonprofit raising a community bail fund. For FTX this simply means taking a 1% fee (on the platform side) for all transactions and donating this to a portfolio of effective charities. At the scale that FTX operates, this approach has yielded over $20m in donations.

In the context of DeFi where protocols and their treasuries are often managed by a community of governance token holders, one hypothetical decision this voting body can make is to distribute portions of these funds to charitable causes or public goods. We might call this just one of many behaviors that can be grouped under ‘headless corporate social responsibility.’ Taking treasury philanthropic grant making a step further, it’s interesting to imagine the hypothetical scenario of a governance body voting to implement features like FTX’s 1% to charity fee on the protocol level. More than just being a one time charitable contribution, this deliberation begins to look like the creation of a system of bespoke taxation — a compelling way to evolve protocol governance beyond its current minimalist state.

Quadratic voting and retroactive public goods funding

Quadratic voting and retroactive public goods funding are quite specific but have implications for the process of philanthropic funding. Both share incentive design as a means of driving greater participation in public goods funding, yet they don’t have much to offer in terms of better public goods selection.

Quadratic Funding is a system by which financial contributors to a set of projects can receive fund matching on the basis of how numerous the population of contributors to each project is. The idea is that more people contributing smaller amounts to a project is preferable to less people contributing larger amounts to a project. This helps incentivize project diversity and “pushes power to the edges, away from whales & other central power brokers.” Quadratic Funding has notably become the core mechanism of the granting project Gitcoin, which is trying to improve upon the risk of nepotism present in traditional 1-dollar-1-vote matching models.

As opposed to funding at the onset of a project, Retroactive Public Goods funding involves funding a project after it has existed for some time, on the basis of evidence of its impact. The amount and direction of funding is based on a results oracle, which at the moment is a fancy way of saying a voting committee with expertise in a thematic area. This mechanism is notably used in Optimism's Ethererum scaling ecosystem.

While useful in the narrow context of funding Ethereum public goods, quadratic voting and retroactive public goods funding are not to be mistaken as solutions for sourcing capital, nor prioritizing which types of issues are worthy of funding in the first place. If Gitcoin and Optimism want to be considered proper philanthropic tools (and not just novel systems for open source patronage), they could expand their definitions of impact. As of now, their initiatives are software centric.

Legibility meets anonymity

Crypto philanthropy presents us with an unusual dynamic of anonymity. In traditional philanthropic contexts we’re used to knowing who funders are. This is partially for reasons of self recognition, such as when a family gets their name engraved on the wing of an art museum. It’s also for legal reasons. Registered nonprofits, even if they don’t disclose publicly who their donors are, need to abide by KYC regulations for the sake of liability and taxes.

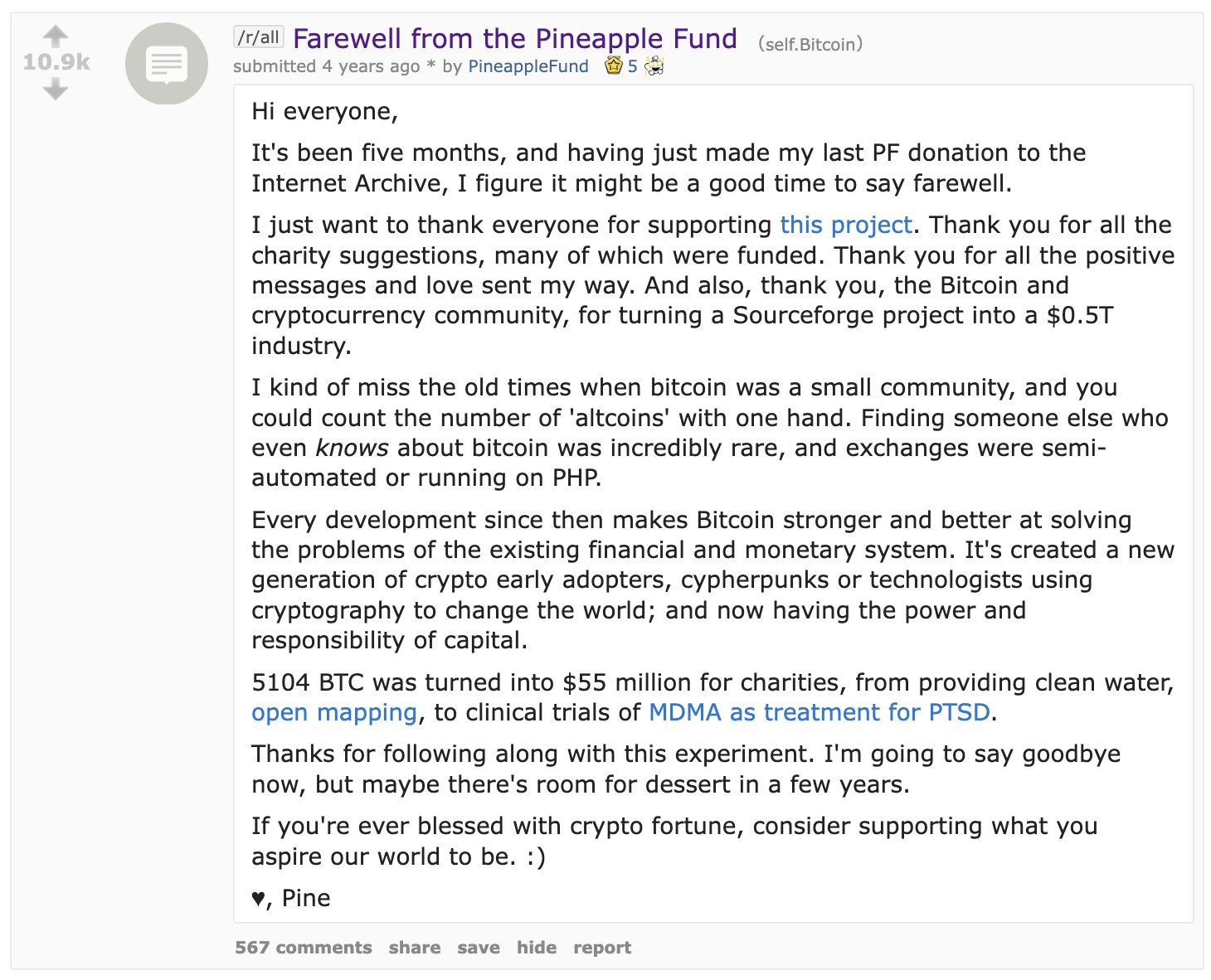

Crypto’s extra-jurisdictional, decentralized nature allows for the idea of true anonymity to be entertained, even if donation transactions itself are public for the world to see. Charities that open up a wallet and publicly list a donation address are essentially creating a one-way channel through which any individual can make a donation. The most historic instance of this occurring was the $55 million Pineapple Fund, which distributed grants as large $5m to 60 different charities vetted by an anonymous donor.

The Pineapple Fund is lauded as a shining example of impactful philanthropy, presumably willed by the option of anonymity. But are there uglier scenarios that anonymity could give rise to? Recently a crypto hacker stole $181m in an exploit of Beanstalk, but not before donating $250k to Ukrainian war efforts. If these funds were donated we would know about their malicious provenance, but what if the hacker had successfully laundered some of these funds using Tornado and then donated them under newfound anonymity? And what if the donation wasn’t to the morally palatable cause of Ukrainian war efforts but to Russian war efforts? We can see how anonymity would begin to backfire. While I personally don’t think that the potential negative effects of anonymity outweigh the positive effects, it’s important to understand the unintended consequences this mechanism enables.

The emergence of philanthropic behaviors in crypto

So far we’ve seen how crypto has given birth to tremendous newfound wealth and a corresponding philanthropic class. We’ve also seen how crypto has led to new ways of pooling together and donating money. We’ve talked about the ‘how’ of crypto philanthropy, but we haven’t really talked about the ‘what.’ What interventions are crypto philanthropists actually funding? In what ways are crypto philanthropists attempting to change the world?

In the not too distant past, you could count on your fingers all the historic instances of donations made from crypto earnings. Now, this giving niche has grown so varied and voluminous it’s not easy to capture its workings in one linear description. As such, I’ll attempt to document a non-exhaustive and discrete list of what I see as the most compelling narratives that are emerging from the world of crypto philanthropy.

To begin, I’ll discuss interventions that can be considered first-order crypto philanthropy, as they were labeled in the introduction. These are programs that revolve around the philanthropic funding of projects whose primary feature is using crypto.

From here I’ll expand the scope to second-order crypto philanthropy — programs that are spurred by wealth from crypto but that don’t necessarily involve the use of crypto.

First-order crypto philanthropy

Consider first the original rallying cry of crypto: permissionless financial tooling and instruments, including everything from safe stores of value, to cheaper and more easily accessible loans, to stablecoins, and more. While most the current use cases for ‘DeFi’ have converged on the self-dealing and hyperfinancialized, it’s not hard to imagine a version of DeFi that serves those who have actually been disenfranchised by traditional financial sector. Consider for example the role that digital currencies and specifically stablecoins play in active war zones like Afghanistan where financial service providers have fled due to fear of fraud and money laundering. Documenting the ongoing Afghani humanitarian crisis, Michael Pisa writes, “by allowing cross-border payments to flow outside of the existing correspondent banking system, cryptocurrencies offer a promising avenue for overcoming the de-risking challenges that Afghanistan faces.” In the city of Herat, Pisa believes that anywhere from $40k to $100k in crypto-for-fiat exchanges happen daily. It’s safe to assume that many of these transactions are humanitarian aid being sent from countries where fiat-to-fiat remittences would have otherwise been blocked.

A more straightforward approach to the financial barriers use case is captured by the nonprofit GiveCrypto, which does exactly what its name suggests. By giving crypto to those in need, initiatives like GiveCrypto are testing out a similar hypothesis to nonprofits like GiveDirectly which believe in the agency of those living in poverty to understand how to best spend resources on themselves. The major difference though between GiveDirectly and GiveCrypto is obviously that, by giving crypto and not local currency, GiveCrypto introduces a major hoop to jump through for beneficiaries. It’s through this significant constraint that neocolonialist dynamics can arise, like those which have taken place at the infamous Bitcoin Beach in El Salvador. As such it’s not clear if crypto-native direct cash transfer programs share the same arguments for impact as their fiat-centric cousins.

Another way to frame the equitable utility of crypto is as a public good. Indeed, this lens has already taken quite a hold amongst crypto proponents. But as, Hart, Lotti, and Shorin point out though, the framing of crypto-as-public good is susceptible to a game of myopic definitions. What one person calls a public good might actually be just an open source software framework that in practice benefits only a narrow population. In order for something to be a true public good its benefits must be freely accessible for everyone in said public, not just hypothetically accessible.

There are other categories of theoretical first-order impacts of crypto that go beyond DeFi and public goods, and for the sake of time, I won’t go into them. The takeaway from these other sub-sectors—such as DAOs, ReFi, and artistic patronage—is similar. Weigh the arguments for impact against the implicit promise of financial returns, not to mention the various acute negative externalities that surround crypto like its carbon emissions profile or its incubation of harmful ponzi-like schemes, and most use cases don’t hold their weight as worthwhile philanthropic initiatives. Even in the scenario where something like ReFi had bulletproof arguments for impact, its speculation-heavy revenue models mean ReFi organizations are frequently well endowed without injections of philanthropic capital. Imagine giving a donation to Tesla.

If there’s one point to be made about the first-order impacts of crypto, it’s that potential is plentiful, but will remain stymied by an inability to focus on how initiatives can benefit those who need it most. In order to unblock its misdirected progress and avoid the price volatility that surrounds a technology with unrealized end-value for users, crypto needs more explicitly purpose-driven for-profits **that aren’t beholden to the interests of whales. It also stands to benefit from more non-profit research organizations that center human utility. First order crypto philanthropy has an opportunity to fund and create more of these types of entities.

Second-order crypto philanthropy

While there are potentially redeeming aspects to it, crypto is not a silver bullet for tough development challenges like the provisioning of clean water and sanitation. Instead of it being the solution, what if it was merely the starting point? In the same way that the Rockefeller Foundation has little to do with evangelizing oil, second-order crypto philanthropy is about using crypto merely as a means of wealth generation and philanthropic currency, while not necessarily being the content focus of the philanthropy itself.

Organizational philanthropy and philanthropcapitalism — the case of Binance Charity in Malta

We can begin by isolating ‘philanthrocapitalism,’ which is used by some to refer to philanthropic behavior pursued with the intention of explicit self-benefit. An example of this a business carrying out greenwashed Corporate Social Responsibility work that aims to bolster public opinion. Think of the Shell Foundation’s international development initiative, or Mr. Beast’s content-driven philanthropy.

The crypto space has no shortage of philanthropy that looks like philanthrocapitalism. Most often it occurs through the dealings of companies and projects before individuals. Organizational philanthropy in crypto starts with same premise as individual philanthropy —someone minted and controlled a large pool of tokens that experienced historic upwards price movement. Just like project founders, crypto organizations themselves hold large sums of their own tokens, usually through the vehicle of a foundation which has grant-making capabilities. A notable example of this behavior can be found in the exchange firm Binance and its native Binance Coin. When launched only a little over four years ago a single Binance Coin traded for $4 where now, even amidst a sharp market downturn, it trades for $280 dollars. This tremendous speculative upside arms firms like Binance with essentially free ammunition to advance its causes, so long as these causes accept cryptocurrency donations.

We’ve seen Binance use this tactic very heavy-handedly in its dealings with the country of Malta over the last several years. Amidst global regulatory uncertainty in 2018, Malta tacitly announced safe harbor to Binance to establish its headquarters and base of operations for EU activities. Immediately following this announcement, Binance donated $200k worth (at the time) of Binance Coins to the Malta Community Chest Foundation via Binance Charity, a bespoke donation platform created by Binance to distribute funds to a preset list of initiatives. Two years later Malta Financial Services Authority began to backpedal on its open-arms stance, partially among fears that Binance was being used for money laundering. It was also around this time that Binance retracted its local donation, which was being used to fund treatments and support for terminally ill patients. After being sued by the Maltese charity in 2021 for failing to transfer their donation, which had appreciated in value to $8m, Binance claimed that their retraction was due to the original terms of donation not being fulfilled. It stated that the donation was contingent upon being able to transfer Binance Coins directly to the charity’s beneficiaries. While this admittedly feel likes an acceptable principle to abide by, it is impractical to make an $8m donation contingent upon 15,000 terminal cancer patients each having crypto wallets that support Binance Coin.

The point of bringing up this messy story is not to moralize about Binance’s role in the situation, but to make its philanthropic motivations clear. It’s not really possible to say that Binance is purely ‘bad’ for making the donation, especially since the firm seems earnestly motivated (by threat of lawsuit or otherwise) to fulfill its terms. Just because philanthropy is pursued for PR doesn’t automatically render its impacts useless. There are other projects under the Binance Charity platform that seem sincerely impactful. But they still leave the door open to the possibility of divergent outcomes for downstream beneficiaries. The primary motivations (public or not) of philanthrocapitalists thus need to be investigated by watchdogs in order to reduce the odds of their initiatives backfiring.

Volatile currencies and legal risks — how donating (and accepting) crypto can complicate philanthropy

Another interesting anecdote from the story above is the dramatic appreciation of a donation Binance made to a small charity. After failing to be sent and therefore cashed out, the charity’s Binance Tokens ballooned from $200k in 2018 to nearly $10m in 2021. Currently it’s a little less than half that. Aa month from now, it easily could be millions more or millions less. Despite being somewhat of an outlier, this scenario makes for an intriguing case study for organizations on the receiving end of crypto philanthropy.

The vast majority of crypto-philanthropic donations are transferred in crypto, not USD. This is partially connected to crypto wealth being born from sitting on large stockpiles of specific project tokens that dramatically appreciate in price. It’s also connected to the tax advantages of donating assets directly instead of cashing out first, which triggers a capital gains event for the holder.

By receiving cryptocurrency donations, a nonprofit is handed the task of exchanging these funds for fiat currencies. This process isn’t easy nor cheap. Its difficulties have given rise to an entire cottage industry of intermediaries that can quickly make exchanges for a small fee. Compared to net benefit of being able to accept donations from a fast-growing donor base, these fees are usually tolerable. But the technical hurdle of setting up this type of intermediary relationship can often prove to be too high for nonprofits which already struggle from technological debt. And even when an exchange mechanism is set up, what happens if it’s not instantaneous, and a nonprofit has to deal with a sharp price decrease while stuck in exchange limbo? It will be important to keep an eye on the inequities created between the nonprofits who are able to jump through these hoops and those who cannot.

The volatility of donations denominated in crypto makes reporting tremendously difficult. Nonprofits have to live up to high standards of transparency and reporting. In many jurisdictions, they are required to submit annual reporting both to the public and tax bureaucracies which document their financial health. The fluctuations of crypto prices makes this point-in-time, PDF-centric reporting practice a massive headache for nonprofit administrators. Similarly, the shifting valuation of donations makes the practice of analyzing philanthropy very difficult.

There’s also the case of economic stimulus organizations that base their operations around the distribution and exchange of volatile cryptocurrencies. GiveCrypto, the various ‘crypto city’ projects, and most dramatically, the country of El Salvador, are examples of centering cryptocurrency as an aspirational economic growth vehicle. Using Bitcoin as a charitable currency might appear to donors as an innovative strategy of passing on upside to beneficiaries. But token prices don’t always go up and price collapse can spell catastrophe for populations already facing financial vulnerability.

Finally, funding philanthropy with cryptocurrencies means that charitable efforts can run into legal challenges. Crypto exists in a regulatory grey area. In jurisdictions like the US, this can just mean uncertainty around taxes until the SEC gives clearer guidance around which cryptocurrencies are in fact currencies and which are securities. In places like India and China, exchanging crypto is technically illegal. There are of course ways to get around this, but in practice it means that cautious charitable initiatives avoid operating in politically-sensitive jurisdictions altogether. Considering that it’s these very jurisdictions where permissionless currencies often have the greatest potential impact, this roadblock is a significant one. In light of these challenges, as well as the general stigma that crypto holds for some, some nonprofits have flat out refused to accept cryptocurrency donations.

Aping into philanthropy, FOMOing into progress — the psychology of crypto investment

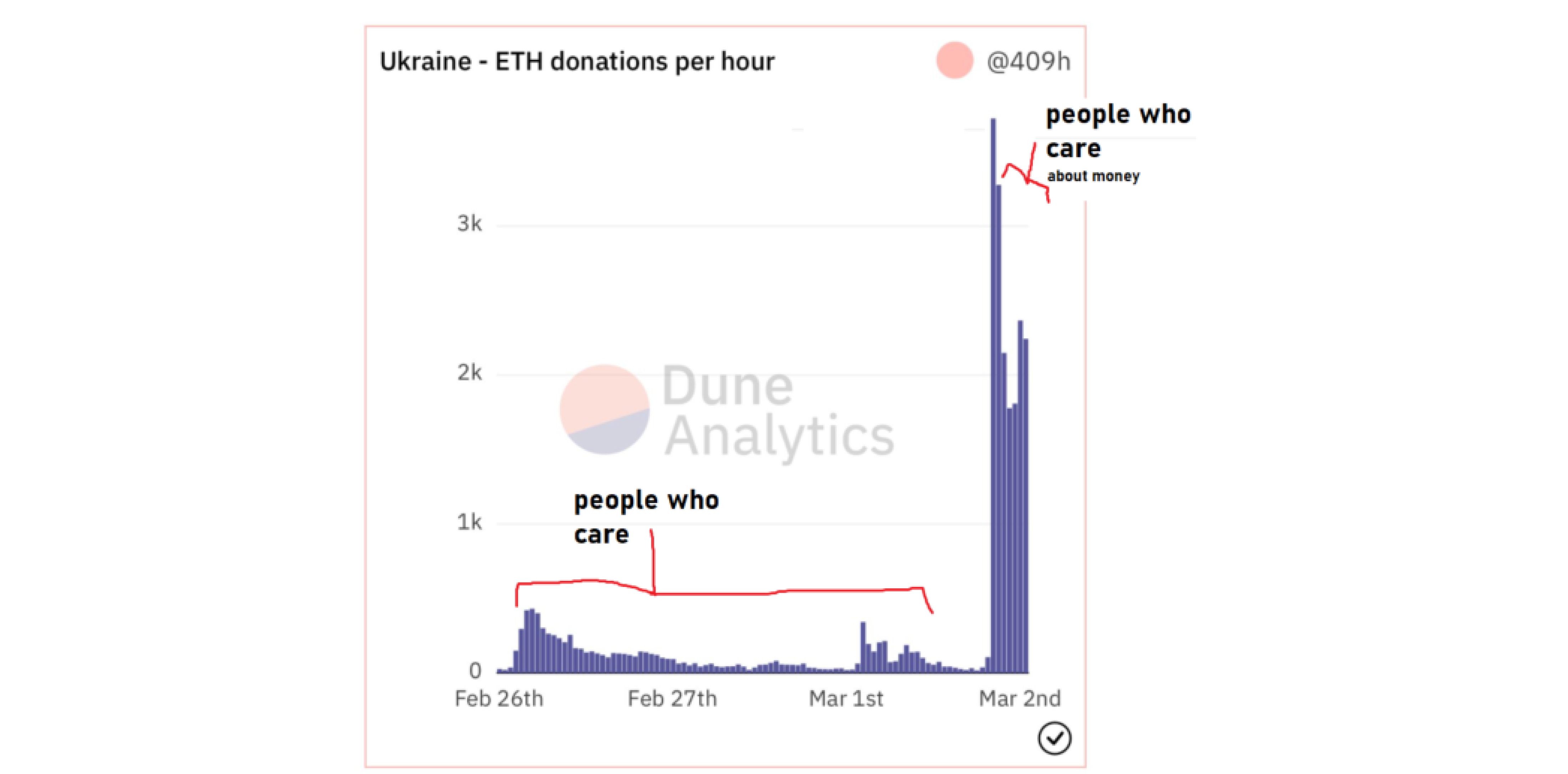

A trademark of the crypto zeitgeist is rapidly mobilizing around a flip opportunity as soon as you see it. When anything can be tokenized and permissionlessly traded, anything can turn into an investment that provides first movers advantage. More than just an investment strategy, the flip trains a new habit of mind that carries over to all sorts of non-investment behaviors. You can ape into that new NFT project your friend posted about on Twitter, but you also can ape into career opportunities, ape into evening plans, ape into a quick walk around the block. This mentality becomes even more irresistible when combined with ‘FOMO,’ or fear of missing out. What you get is not only an individualistic incentive to ape into something, but the added peer pressure of everyone else doing it. This psychological cocktail makes for very fast group mobilization times. In crypto all it takes is a viral tweet, an ETH address, and a few hours for hundreds of millions of dollars of capital to flow into a completely new asset or vehicle.

This attitude can apply to making donations just as much as it does investing in assets. Although it can lead to increased participation, is it the best mindset for pursuing philanthropy? Or does it better fit the profile of distributing aid?

A slightly cynical reading is that aping into philanthropy simply looks like any other self-profiting crypto behavior. It’s a transaction with the primary motivation of financial gain and secondary motivation of loosely doing good. Examples here include the previously cited charity tokens or NFTs that donate trading fees to charitable causes. A more clear-cut example would be people who donated ETH to Ukraine’s war efforts in hopes of getting whitelisted for a rumored token airdrop. Move fast enough and you not only can have your cake, you can eat it too.

But there are plenty examples of charitable behavior from the crypto community that don’t carry with them a quid pro quo. During the outbreak of the Delta COVID variant in India in the spring of 2021, we saw the crypto community mobilize very quickly and impressively around the distribution of aid. CryptoRelief was set up seemingly overnight, and Vitalik Buterin infamously regifted ~$1b worth of Shiba Inu Coin (SHIB) that had been airdropped to him. While the organization faced some initial hiccups around converting crypto donations into on the ground impact, they eventually were able to distribute over $55m in grants.

The expediency of CryptoRelief’s formation and capital absorption was partially connected to the immediacy of the crisis unfolding in India. Even if now it feels like a distant memory, back in Spring of 2021, India’s COVID misfortune was the source of tremendous empathy across the world. Although this empathy was universal, crypto did and does potentially separate itself from other groups in its ability to quickly coordinate, pool capital, and distribute it to those in need. In this light, you can think of the entirety of crypto twitter as a supercharged GoFundMe page where intermediary-removal combined with the ape/FOMO mindset greases the flywheels of charitable behavior.

While it’s remarkable just how much and just how quickly the crypto community can raise for causes like COVID relief or the Ukrainian war efforts, it’s important to recognize that these fast mobilization times can have negative consequences too. Even though sending ETH doesn’t require an intermediary, creating positive charitable outcomes fundamentally does. This is true both for logistical and expertise reasons. Crypto donations need to be converted into local fiat and, most importantly, there needs to be someone who is able to competently evaluate the best places to send this money. The dangerous thing about lubricating the charitable process too much is that the importance of a funding strategy can be overlooked. Doing charity might be as easy as hacking together a website and a wallet, but doing good charity is a deliberative process of costs and benefits that even experts can get wrong.

This insight points toward an increased need for crypto-native charitable middlemen. These are actors who are able to equally straddle both worlds and reliably usher well-intentioned donors towards the most impactful outcomes. This is a job that crypto charity platforms like Endaoment can only fulfill to an extent, as ultimately there is no automation that can replace the on-the-ground expertise.

Finally, it’s worth considering how the crypto mentality applies to not just humanitarian-styled aid, but to philanthropy where there’s no predetermined outlet for funds and the donor’s personal ambitions shine through. It’s been noted elsewhere in this piece how it’s difficult to describe trends about philanthropy that aren’t anecdotal. Philanthropists operate in a pluralistic context where their financial independence means that anything is fair game. The cultural alignment among crypto entrepreneurs means that they take the same approach to problem solving, even if they focus on different causes. In this sense we can contextualize crypto workers as loosely carrying forward the rationalist lineage of tech workers, but adding to it a sense of entropy, nihilism, and weirdness.

Many of the trademark features of the 2010s tech zeitgeist have found their way into tech-originated foundations like Open Philanthropy and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. These organizations appeal to evidence, metrics, rationalism, and the outsized ambition that could only come from the sincere belief that, not only is software eating the world, it’s my software that’s doing the eating. What will crypto’s version of these industry-mirrored philanthropic values look like? We can probably expect some lingering rationalism to enter the picture, but what’s most notable about the crypto industry is its irrationality.

im no longer motivated by money and purely motivated by changing the world in the lulziest ways possible

— imhiring.eth (@mikedemarais) December 3, 2021

What might “changing the world in the lulzest ways possible” manifest as? Maybe building a widely adopted crypto wallet styled with rainbows fits the bill. But might it also mean handing out a historically large amount of free weed? While we won’t be able to predict specifics, crypto philanthropy will likely drift further into the chaotic-good quadrant than any philanthropic paradigm that came before it.

Cypherpunk visions, scientific progress, and longevity research

More specific than “lulz”, crypto philanthropy can be grouped into several thematic concentrations to date. These niches show us that world-changing amounts of money are already flowing into certain types of philanthropic initiatives.

One group lays loosely around the spreading of cypherpunk ideologies. Not coincidentally, this was one of the first shared philanthropic directions from crypto. In 2011 when Bitcoin was the only cryptocurrency of importance, various donors combined to give 3,505 bitcoin to the Electronic Frontier Foundation (about $3,500 at the time, although it appreciated tremendously over the next two years). Nearly a decade later, the highest price fetched for an NFT would be Edward Snowden’s Stay Free which sold for $5.4m. A year after, that the group FreeRoss DAO would break the record once more with their purchase of a $6.2m NFT in support of Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht. Despite these high profile donations, it’s difficult to determine the depth at which crypto-philanthropists appeal to cypherpunk values. There is no crypto-native EFF, nor is there even a nonprofit that teaches infosec best practices. Maybe this is a product of the value drift that crypto has experienced over the last decade. Maybe pro-privacy crusades will take on new relevance in response to future changes in the geopolitical landscape.

But there is one extremely clear modern through-line to crypto’s cypherpunk origins. It comes in the form of scientific progress, specifically the transhumanist niche known as longevity research — the science behind slowing (and even reversing) aging. Pre-Bitcoin crypto enthusiasts like Hal Finney showed an interest in this field, and the connection has never really gone away. If Vitalik Buterin acts as a kind of philanthropic figurehead for crypto, longevity is one of the issues he takes most seriously and has funded in the order of hundreds of millions.

If we're being more open minded about accepting new weird ideas, can I suggest anti-aging research? Aging is a humanitarian disaster that kills as many people as WW2 every two years and even before killing debilitates people and burdens social systems and families. Let's end it.

— vitalik.eth (@VitalikButerin) March 30, 2020

We see a generous support of longevity research from more than just Vitalik. VitaDAO and NewLimit demonstrate interest from mostly a for-profit perspective, but maintain philanthropic operations through fellowships. Impetus Grants deploys tens of millions into longevity research. Most of its funds come from crypto wealth.

Perhaps in addition to its cypherpunk sensibilities, longevity research is attractive to donors on the basis of fitting in nicely with concurrent contemporary movements around accelerating the pace of scientific research. Whether it’s ‘fast grants’ styled grant-making, or the crypto-native ‘DeSci’ (decentralized science) movement, both approaches favor funding initiatives that wouldn’t be first in line for NSF grants. Considering its novelty, potential upside, weirdness, and niche stature, it makes sense that longevity research is a favorite target for crypto philanthropists.

Effective Altruism and the SBF effect

Outside of longevity research, the only other unambiguous focal point of crypto philanthropy is effective altruism (EA). Effective Altruism is a philanthropic discipline concerned with using one’s time and money to do the most good possible. It selects cause areas on the basis of evidence and reason for impact. Often, EA ends up focusing on lowering existential risks like misaligned AI, or intervening in neglected areas of global health. While EA has grown quite popular among tech-adjacent crowds in recent years, the connection between crypto and EA is mainly a story of specific individuals and small sample sizes. Vitalik once again deserves mention here with his $54m donation to GiveWell. So does BitMEX exchange founder and Giving What You Can pledge signee Ben Delo. But the most important name to cite whenever discussing EA and crypto philanthropy is undoubtedly Sam Bankman Fried.

SBF is an outlier in the crypto space. Long before he would begin working on his exchange, FTX, SBF was committed to the principles of EA and specifically a career pathway known as earn-to-give, in which an individual seeks to make as much money possible for the explicit purpose of donating the majority of it to effective charities. After setting this intention for his career, a number of factors came together to set SBF on the course to become the richest person in the world under the age of 30. First there was the peak of a historically bullish market, and the sharp rally of crypto assets tied with early COVID economic recovery. Next there was SBF and his colleagues’ cunning to not only build FTX, but aggressively capitalize and market it so that it would grow from obscurity to the second largest exchange by volume in only a little over a year. In the process SBF amassed tens of billions, all while maintaining the explicit goal of giving it all away.

Although SBF has and will continue to make large political donations, he recently revealed his first major vehicle for espousing EA values. Early in 2022 the FTX Foundation launched its Future Fund, a $100m/year grant-making body aimed at addressing a set of cause areas that seem to have one foot in EA and another in progress studies. Despite the recipients of funding only just being announced, it’s already clear that the Future Fund has a penchant for funding equally impactful and unconventional projects, which is often the balance philanthropy strikes when it’s at its best. ‘Space Governance’ is one example of a novel cause area the Future Fund is looking to support.

@benthamite #crypto billionaire sbf ❤️s #effectivealtruism ♬ sonido original - Benthamite

SBF is in a class of his own with the size of his wealth and high commitment to philanthropy. Despite being a household name, SBF hasn’t demonstrably inspired others in crypto to follow in his EA footsteps, nor even to mimic his style of earning-to-give for any other philanthropic niche. Some might find SBF’s cargo shorts lifestyle endearing, but that doesn’t mean they’re going to adopt his utilitarian values for themselves. Maybe this is on account of the recency of his ascent; more time is needed for his influence on the philanthropic ambitions of his crypto peers to percolate. Or maybe there is an uncrossable divide between SBF’s high ideals and the materialistic motivations of the average crypto bro. There are also plenty of individuals who are uninspired by effective altruism and perceive SBF’s earn-to-give pathway as just another chapter in the long history of philanthropic charades. This camp questions whether “doing good” can justify aggressive profit-seeking behavior.

The future legacy of crypto philanthropy

Philanthropy often gets lambasted for its inner hypocrisy. What good is downstream philanthropy if the upstream source of its funds is damaging to society? For Carnegie this meant comparing the detriments of his union-busting tactics against the merits of his libraries. Such a difficult comparison leaves the legacy of many philanthropic projects as difficult to summarize beyond “it’s complicated.” For SBF, FTX’s reputation as a casino for ponzi-like digital assets complicates the moral status of his philanthropy. In the eyes of a certain type of anti-establishment value investor, SBF’s business actions are as immoral as the actions of the bankers that set in motion the 2008 financial crisis. Simultaneously, it’s possible that there has never been an individual as committed to large scale impactful philanthropy as SBF is.

Coming to terms with philanthropy’s contradictions is a healthy reflection of a society questioning how it can solve its wicked problems. High among these are wealth inequality and corresponding elite capture of institutions. But the questions of “are billionaires bad?” or “is crypto bad?” are notably different from the question of “is philanthropy bad?”, and those concerned with progress need to be able to decouple the two categories. It’s a tall task to weigh SBF’s supposed negative business externalities against his philanthropic positive externalities. In the US (and the The Bahamas) tax and securities regulation are currently set up in a way that perfectly legalizes FTX. Foundation law permits the FTX foundation to spend its money as it pleases. Until these laws change, or until SBF is found to be breaking them, we should view philanthropy as emergent byproduct of this system and as a standalone behavior that should be judged on its own merits.

While there are examples of philanthropy, especially corporate philanthropy, that are pursued for the sole sake of bolstering negative corporate reputations, most philanthropy, as unprovocative as it is to say, is pursued with good intentions. This is even true of crypto philanthropy. Good intentions only mean so much though. It’s up to the public, working in conjunction with the fourth estate, to assess any given philanthropic project’s difference between good intentions and positive impact. If philanthropy is, in legislative contexts like the US, an unavoidable byproduct of wealth creation, and we’ve built a society where wealth creation is a primary motivator. We need to embrace philanthropy as not a pet project of the rich, but a core driver of collective progress.

Crypto philanthropy’s shortcomings

In the case of crypto philanthropy, mere good intentions have on average yielded a style of philanthropy that actually converges on charity, even if outliers exist. I’ve alluded to the distinction between charity and philanthropy throughout this piece, but for the sake of summary and clarity, here are the main areas where crypto philanthropy’s ambitions falls short.

- For interventions like wartime aid or COVID relief, sensationalism, in-group mimicry, and affective empathy drives participation more than any kind of affirmative vision for progress. These drivers aren’t problematic, but they make impact a lesser priority.

- Similarly, when crypto projects and companies facilitate philanthropy themselves, perverse incentives for positive PR outcomes have potential to decrease impact.

- The over-reliance crypto philanthropists place on funding projects that require using crypto as means of impact itself (first-order) ultimately leads to lesser outcomes. While crypto unlocks novel and compelling philanthropic mechanisms and removes financial barriers, not all interventions require its use. In situations where crypto does have a first-order argument for impact, this impact is often stymied by highly speculative underlying tokens that create instability for nonprofits without the technical ability or financial health to mitigate risks.

- Crypto claims to be highly supportive of public goods, yet its version of public goods aren’t very public, nor are they always serving a clear good. In reality crypto public goods more often than not mean open source software libraries that, while neutral themselves, are used in practice to scale DeFi-adjacent applications with indirect human utility. This isn’t even to mention the fact that crypto public goods’ non-excludability is often contingent upon being part of the very small fraction of the public that understands smart contract engineering.

What’s compelling about crypto philanthropy

Not everything about crypto philanthropy is lackluster. For one, the value exchange and group coordination mechanisms that form the basis of crypto have a clear case for improving some of the longstanding inefficiencies and inequities of philanthropy. When it comes to programming, ambition can be found in a few exceptional donors. For these individuals are not only ambitious relative to other crypto philanthropists, they’re pulling the entire philanthropy sector in more interesting directions.

To summarize, here are the main aspects about crypto philanthropy that are compelling.

- In a world where the costs around setting up payment rails and transacting in crypto goes down, nonprofits stand to benefit from more agile ways of accepting and transferring money to end recipients.

- For a small group of the largest winners of the crypto boom, entrepreneurial vision is correlated with philanthropic vision. For Sam Bankman-Fried, this idea is taken to such an extreme that his entire reason for working in crypto is to generate wealth for philanthropic activity. For less extreme cases, like Vitalik Buterin’s funding of longevity research, there is a clear drive to use earned wealth to create beneficial outcomes for society. Even though many among this population have yet to reveal their full philanthropic ambitions, we can expect to see more philanthropic activity in the medium term future as crypto industry reaches its plateau of adoption and founders set sights toward new endeavors.

- Beneath crypto’s skin-deep layer of greed, crypto advocates share a sincere desire to change the world. Expected financial returns alone rarely create manias but the siren song of money and progress is a different story. Crypto’s direct rebellion against the perceived infractions of the web2 platforms that came before it still lingers. But the meager adoption of web3 cures for web2 problems has led to parts of crypto feeling far removed from its original vigorous ideology. If crypto as a first-order solution for progress continues to falter, second-order crypto philanthropy will grow in popularity as a way to provide a clearer answer to the good that crypto philanthropists can achieve.

What’s new and uncertain about crypto philanthropy

Finally, there are several aspects of crypto philanthropy we’ve touched on that aren’t necessarily good or bad, but are simply different. Regardless of outcome, they all are changing the way philanthropy is practiced.

- While philanthropy that transacts in volatile currencies can create instability in donation valuations, there are many examples in the short history of crypto philanthropy of these donations leading to extraordinarily large financial upside for nonprofits. From a cost benefit perspective, it could be beneficial for nonprofits to intentionally not immediately cash out on certain crypto donation types where this potential upside exists.

- Philanthropic DAOs are an interesting way to experiment (at least) with grant making deliberations, and (at most) with the notion that philanthropy is an individualistic practice. Will a more participatory philanthropic allocation process flounder amongst the friction of decentralized governance the same way that DeFi protocols do? Or will horizontal philanthropic structures create more equitable and democratic funding outcomes?

- Protocol philanthropy, which might be considered a subset of ‘headless CSR,’ relates to the control a voting public maintains over assets held within a decentralized protocol’s treasury. This is technically similar to a philanthropy DAO but in practice different along the lines or purview. While a philanthropy DAO’s primary purview is distributing philanthropic capital, for a protocol treasury this job might be much further down the order of priority, if it’s even recognized as a job at all. It’s in this affirmative reflection, “this is our money, we can spend it how we want,” that seemingly unaligned DeFi protocols like Uniswap can choose to pursue philanthropic outcomes. Potential is there but for a voting public that cares about fiscal conservatism, it is by no means promised.

- The crypto community exhibits extremely fast collective mobilization, crudely captured by the psychology of ‘aping’ into decisions. Just as much as this sentiment can be used to sell out token sales, it can be used to solicit increased donations and philanthropic participation. But just because it’s easy to click ‘send’ doesn’t mean that the thing you’re sending to is properly vetted. Generally, the types of initiatives that are more susceptible to this FOMO logic are those that are sensationalized, which also tend to make for bad philanthropy.

What is the future legacy of crypto philanthropy? Philanthropy is a discipline of scattered ambitions. It’s difficult to speak to the comprehensive merits of an entire philanthropic sector. But if you had to draw a regression-line between its data points, crypto philanthropy could largely be understood as an ascendent, nascent, and at times, a misdirected niche.

This is only a present-day reading, and in the future crypto philanthropy very well could grow into something greater. The capital is there, even if the ambition is still incubating. If this shift occurs, it will be because crypto philanthropists decided to deemphasize crypto as a means and ends, and instead focus on it only as means. Ultimately the most impact will come from thinking of crypto as just one of many tools that can be used to create progress.

More than a matter of appropriate tooling, moving beyond first-order crypto philanthropy requires philanthropists to affirmatively envision what kind of world they want to live in and what problems they want to solve. Maybe this vision is of a world where lowered financial barriers radically reduce poverty. Maybe it’s a world where age-related diseases don’t exist. No matter what it is, good faith crypto philanthropists should pursue their causes in a way that seriously attempts to make progress. PR boosting, virtue signaling, and tokenization plays are fine as long as they don’t come at the expense of impact. Rarely is this the case though.

When philanthropy is done right, it has a way of superseding the baggage that might otherwise surround the idea of billionaires building the world in their vision. When it goes wrong it reifies the narrative of elite takeover. Consider the case of MacKenzie Scott, whose recent donation spree has overnight set a new bar for the potential of graceful philanthropy. We might never be able to say conclusively that crypto is good, but we can at least strive for good crypto philanthropy.

If you need help building it, please contact Other Internet.

Thanks to Nadia Asparouhova, Tom Critchlow, Sam Hart, and Gary Zhexi Zhang for feedback.

©2024 Other Internet Research Institute